Rate setting is no simple task, but there’s a reason we pay what we do.

In 1864, Pueblo residents could purchase a 60-gallon barrel of Arkansas River water for 25 cents from the back of a wagon. Anything swimming or floating in it came as part of the deal. It might have seemed like a bargain for a cowboy looking to clean up before a night on the town or seeking a cool drink on a hot summer day.

Today, both the treatment of Colorado’s water and the price structure are far more sophisticated. Just as there is a science to treating water to meet standards for health and safety, the pricing of water is closely studied. Water utilities across the state provide water that is much cleaner now, meeting standards that measure contaminants in parts per million, billion or trillion. And that 60-gallon barrel? Today, it would cost just 13 cents to fill from a Pueblo tap.

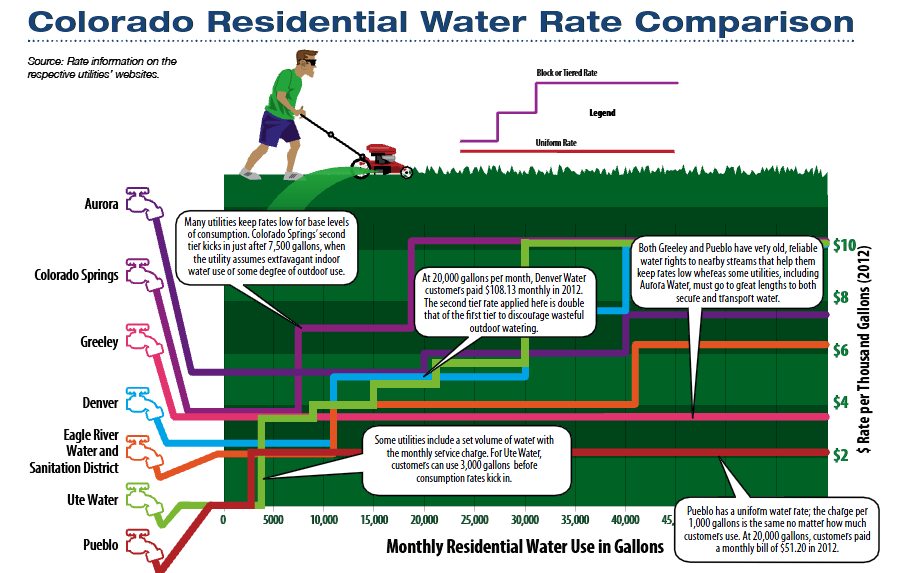

The price of that same Arkansas River water varies as you travel up the road. In Colorado Springs, a growing city located farther from natural water sources, complicated systems transport water over long distances, affecting cost. Customers there would pay nearly twice as much as in Pueblo, given a minimum level of consumption, and more than three times as much at the top of a tiered rate structure that increases the rate as more water is used.

To the north, Aurora Water moves Arkansas River water over mountain ranges into its system in the South Platte Basin to use and reuse until the water is technically “used up.” The city charges customers who use lower amounts of water more than Colorado Springs does, but bills big users a little less.

Why the differences?

No Industry Rule of Thumb

Every system is unique, and every utility has some sort of rate structure that takes into account the cost to buy water, treat it, pump it and maintain the infrastructure that delivers potable water to consumers’ taps.

Going back to the Old West example, some of the water might spill from the barrel and there is more wear and tear on the wagon and horses as you haul it further up the road.

The American Water Works Association provides guidelines for utilities in setting water rates, but more depends on the boards that govern cities, utilities or water districts and the nature of water systems. A developed water system with few capital costs likely will be able to keep its rates on a steady plane, while growing communities have to develop strategies that avoid rate shock while paying the bills.

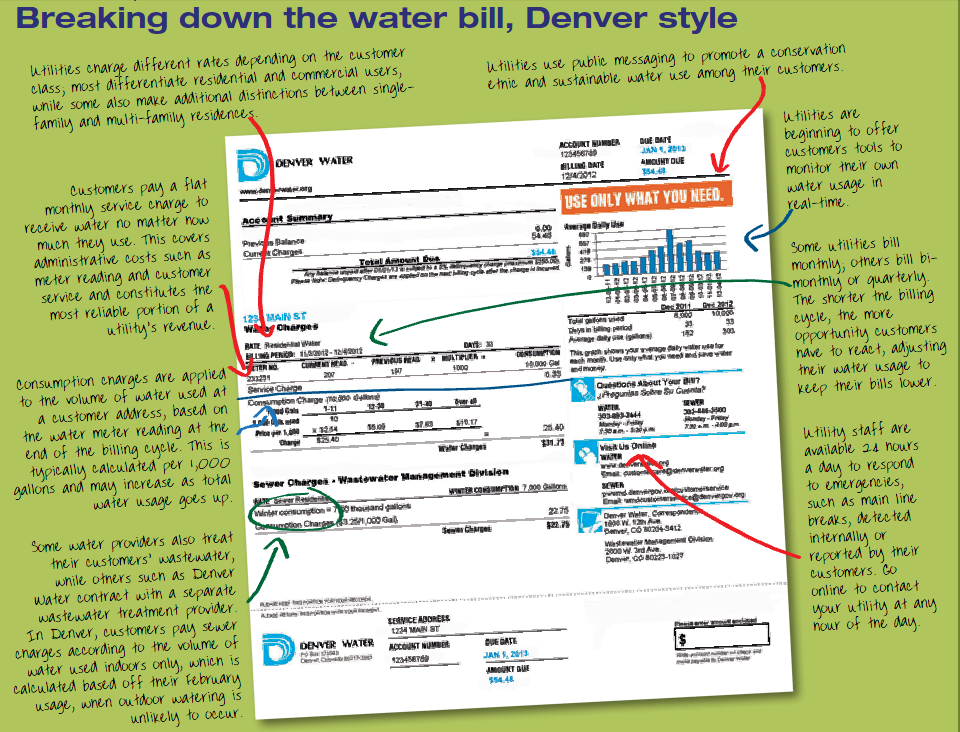

Costs for water might depend on source of supply and whether the water comes from a system owned and maintained by the utility or purchased from another provider. If new, permanent water supplies must be acquired, the relative seniority and resulting dependability of the water rights also affects cost. In addition, some special districts rely more heavily on property taxes, particularly for capital improvements, which can offset the need for higher customer charges. But this diminishes flexibility—certain constitutional limits apply to property taxes but not service fees. Water bills may also include sewer and stormwater charges.

Beyond those factors, a growing community might require new users to foot the bills. “In simple terms, you’ve built it before they come,” says Rick Giardina of Red Oak Consulting, which assists hundreds of water utilities across the country with setting rates and other operational issues. Utilities build the cost of new service into one-time, up-front tap fees—virtually invisible charges included in the price of a new home or business. If those fees are set too low, existing customers could wind up footing a larger bill than necessary.

Social considerations also come into play when structuring rates. Some utilities might subsidize a minimum level of consumption to keep the price affordable for those least able to pay. Such an “essential use allowance” is typically based on the amount of water an average household would use for indoor use only. Similarly, a utility could delegate a portion of its revenue toward a payment assistance program.

A community might also use rates to attract large commercial users, charging them lower rates while asking residential customers to make up the difference; the benefit could be realized through economic development and an increase in the local tax base.

The rate structure could also be used to promote other social goals such as low-impact development or green infrastructure that conserves water, says Giardina. “In the work we do, the first question we’re asked is ‘How do we compare with others?’ But without peeling back the layers of the onion, there are so many variables.”

Financial Realities

Elected boards often want to keep prices affordable to keep customers happy, but at the same time use rates to encourage conservation. They must also strike the tricky balance between maintaining revenues to cover today’s costs, while at the same time planning ahead for capital improvements. The job takes leadership and political will— there can be pushback from customers for throttling up rates too quickly.

Old West advice: Avoid a lynch mob at all costs.

At Aurora Water, Steve Hellman (left) manages the finances, while Greg Baker (right) manages public relations. Communicating the variables behind water rates is a joint effort. Photo By: Kevin Moloney

Aurora faced criticism from some ratepayers for increases to pay for the $638 million Prairie Waters Project, which recycles effluent through a complicated well-field, pipeline and treatment system. Its rates jumped 12 percent from 2006 to 2008, and then by 7 to 8 percent in the next two years.

The board of the Parker Water and Sanitation District narrowly escaped recall in 2009 when the costs of building the Reuter-Hess Reservoir hit home. And now the proposed $500 million Arkansas Valley Conduit has Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District representatives busy reminding officials in 40 communities of the decade-long planning process that has gone into trying to make the project a reality.

Colorado Springs customers are now paying higher rates to cover the cost of the $986 million Southern Delivery System, currently being built. Beginning in 2011, Colorado Springs Utilities told customers to brace for six years of 12 percent annual increases in water rates before the new system is expected to come on-line in 2016. In 2013, the actual rate increase will be 10 percent, and smaller jumps are anticipated in 2014 and 2015.

Even little changes can cause big ripples. In Center, a small community in the Rio Grande Basin, a proposal to install meters got residents’ attention last summer because it was feared rates would double.

“Public utility governing bodies are torn between public resistance to rate increase and the financial realities of operating and maintaining the system,” says financial consultant Joe Drew.

Utilities have about 80 percent fixed costs, while 80 to 90 percent of their operating revenue typically comes from customer charges. Yet they must maintain and replace parts in the water system. “In tough economic times, you can’t say that you can’t afford to improve your water system the same way you can’t afford to put a playground in the park,” says Giardina. “A community can say, ‘We’re willing to accept lower levels of services.’ But you can’t deliver half-clean water.”

Strategic Rate Setting

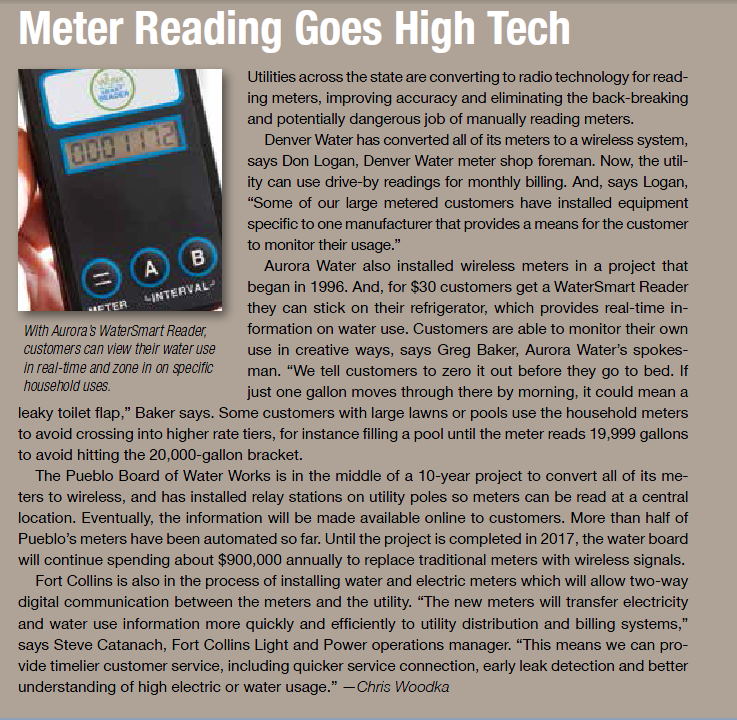

Nearly every community in Colorado uses water meters to track customers’ water use for monthly or quarterly billing. Some still charge a uniform rate for all customers, regardless of the amount of use. As populations grow, many water providers have implemented tiered rate structures that charge more per gallon as use increases. A few have taken the next step, creating a water budget that reflects a homeowner’s likely needs and past use of water.

The Pueblo Board of Water Works is one utility that uses a one-size-fits-all water rate, which means customers pay the same price per 1,000 gallons whether they use 10,000 or 40,000 gallons per month.

The reason Pueblo is able to do that is because it has acquired enough water to meet modest future growth needs and uses its excess supply to keep rates low. It also has some of the oldest water rights of any Front Range city, which insures its ability to use water from the Arkansas River that flows through town. Pueblo also strives for only moderate rate hikes by planning for capital improvements years in advance.

“My personal philosophy is to use small, steady rate increases,” says Seth Clayton, finance division manager for the Pueblo water board. “You want to keep rates as low as you possibly can, because it provides flexibility for the future.”

In the early 1980s, a time of national inflation and local water plant improvements, the Pueblo Board of Water Works upped its rates between 6 to 11 percent annually. Then, for nearly a decade there were few increases, but since 1995, the board has inched up its rates between 1.5 to 5 percent annually, but no more. Even during a $60 million supply-boosting acquisition of shares of the Bessemer Ditch in 2009, the board found other ways to soften rate increases.

Pueblo routinely uses its water to create other revenue streams that offset the need for higher rates. The water board leases water to farmers, power companies and Aurora to provide between 20 percent and 25 percent of its revenue. During the drought of the last two years, the water board started increasing the price for leasing water both through competitive bids and short- or long-term contracts.

After the drought of 2002, the increasing scarcity of Colorado water supplies hit home, and most cities and water districts along the Front Range adopted some sort of tiered rate structure to discourage wasteful water use.

In Old West terms, the first barrel of water still might cost 25 cents to cover the basic costs of bringing clean water to the customer.

Under a tiered rate structure, the second barrel, perhaps for a really thirsty cowboy, would cost 50 cents. If the cowboy hankered for a bath every night, the third barrel would cost a dollar.

According to Stella Chan, financial planning manager for Colorado Springs Utilities, studies have shown that for every 10 percent increase in the price of water, residential users reduce consumption by between 1 percent and 7 percent.

Some tiers are steeper than others, and in some cases have been set through trial and error. Aurora Water uses its rate structure— its second attempt at tiered rates— to reflect a higher cost during the summer lawn-watering season. After decades of acquiring new water sources and building Prairie Waters, Aurora now has some of the highest water rates on the Front Range.

Still, Aurora Water’s chief financial officer Steve Hellman believes the city of more than 335,000 people has positioned itself well in terms of future rate increases. About 40 percent of the cost of Prairie Waters depends on new development—the tap fee for a single-family home is more than $40,000, compared to $4,000 in Pueblo.

But the city can’t afford to put costs on the backs of existing customers should the growth be slow in coming. Aurora has not had rate increases in the past two years, and does not expect to ask for more than a 2 percent increase through 2015. Like Pueblo, Aurora uses sales of leased water to offset costs and avoid rate increases.

“This year [a drought] was great for sales, and we’re using the money to pay off the extra debt,” says Hellman. Aurora Water may also sell water to its neighbors in the South Metro area through the Water Infrastructure Supply Efficiency (WISE) partnership.

Colorado Springs, one of the first Colorado cities to implement meter reading, started its tiered system in the summer of 2003, during a drought where outdoor watering was restricted. The higher rates kick in at lower levels than under Aurora’s structure.

“When we look at the average summer usage per residential customer in 2005—the last year that mandatory restrictions were in

place—and the average between 2006 and 2011, the [per capita] usage hasn’t gone up,” says Chan. “So, one can conclude that the tiered rate structures and the price signal do encourage conservation.”

Another conservation-minded pricing strategy, used in a few communities such as Boulder and Highlands Ranch, is to develop customized tiers based on each customer’s specific needs. These utilities create individual water budgets for each customer based on variables such as customer class, the number of people living in a household and a reasonable allotment for outdoor landscaping needs, plus past use on an account’s record.

In Old West terms: “You used a barrel last week, so that’s all we’re bringing this week, partner. You want more? You’ll pay more.”

Customers in Boulder who stay within their budget pay a lower base rate. But penalty rates for exceeding that budget can reach 500 percent of the base rate. Again, the idea is to send a price signal that makes people think twice about the way they use water.

In addition to billing through a water budget, the Centennial Water and Sanitation District, which serves Highlands Ranch, provides detailed information to its customers about how much water outdoor landscaping actually requires. Water bills each month clearly state the water usage goal for each customer.

For tiered rate structures or water budgets to be effective, customers must have the ability to track their use and make adjustments. Infrequent billing cycles, for example, limit customers’ ability to coursecorrect in their water use.

Conservation Conundrum

Pricing strategies that reduce customer water use can also lessen the need to develop new water supplies or fund additional water treatment. But, Giardina cautions that “conservation pricing can lead to a permanent decline in water use, and you have to ask, ‘How much lower can we go?’”

The Alliance for Water Efficiency, in a paper presented at a 2012 national water rates summit in Racine, Wisconsin, outlined a dilemma facing water utilities nationwide. As people use less water through conservation and efficiency measures, they inadvertently drive up rates. Utilities end up selling less of their product, but still have to cover fixed costs. To make up for decreased sales, they must raise rates further. Customers are effectively penalized for their successes.

“The biggest risk for the industry may be building tomorrow’s water supply infrastructure to meet yesterday’s water demand,” authors Janice Beecher and Thomas Chestnutt contend.

For small utilities, the job of rate setting is simply a matter of keeping up.

La Junta, an Eastern Plains city of 7,000, has embarked on several $1 million-plus projects since 1999, including a reverse osmosis treatment plant, new supply, expansion of the system, two new water tanks and partnerships with nearby districts. “For a town our size, these have been huge projects,” says Joe Kelley, La Junta’s water superintendent.

Just as for other water utilities across the state, La Junta must also adjust rates to keep up with increasingly stringent regulatory requirements. Rising energy costs—it takes a lot of power to pump water through a system—also drive up the need for revenue.

The charge for 11,000 gallons in La Junta has gone up to $51.71 in 2013 from $43.30 in 2009, a 19 percent jump. The rates are likely to continue to rise in the future, as the community is one of 40 participating in the $500 million Arkansas Valley Conduit. The conduit will provide clean drinking water to communities feeling the pinch of tighter water quality standards. “I think people here are pretty comfortable with the conduit, and realize it is the most economical alternative at this point,” says Kelley.

That comfort level might reflect a notion suggested by financial consultant Joe Drew: People in rural communities have a better understanding of where their water comes from.

Kelley isn’t so sure. “Even in La Junta, most people think water comes out of a tap,” he muses.

Better than from a barrel in the back of a wagon.

Print

Print