A federal registry called the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System pays tribute to the nation’s free-flowing waterways for their, well, wild and scenic nature. The list grows as federal agencies charged with evaluating rivers on public land for their “outstandingly remarkable values” (ORVs) deem individual segments suitable and win community and legislative support. Of the 203 rivers now protected as such, Colorado has only one—the Cache la Poudre above Fort Collins, 76 miles of which made the grade in 1986.

“We’re avoiding tunnel vision about Wild and Scenic. This is a much broader discussion.” – Wendy McDermott

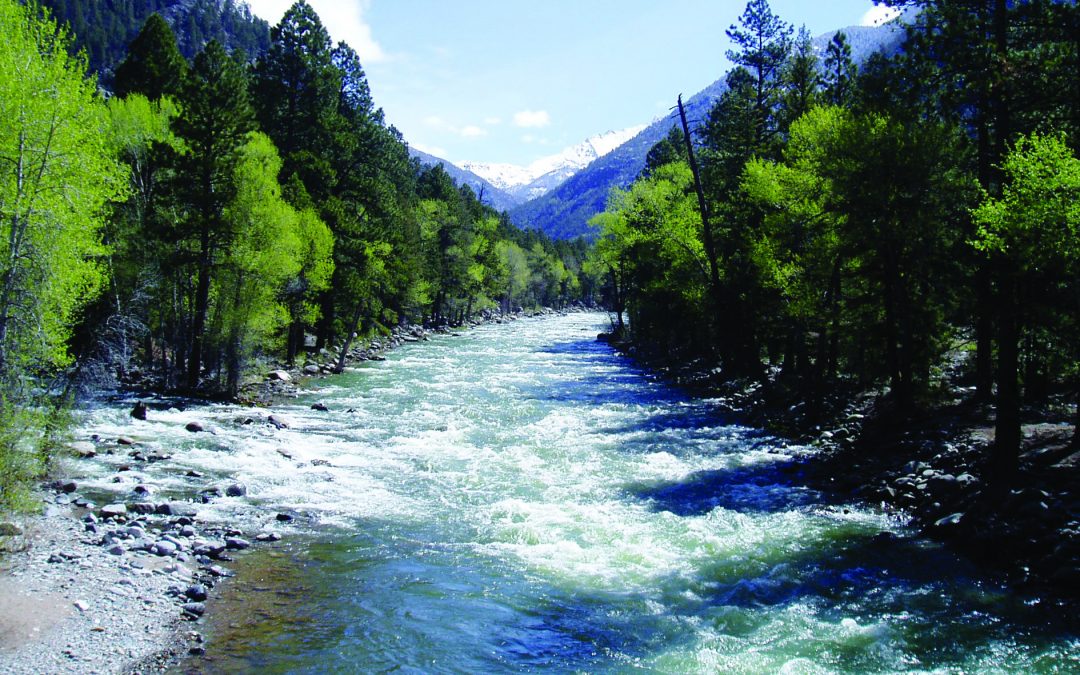

In southwestern Colorado, the San Juan Citizens Alliance plays watchdog to local natural resources, including regional streams. When the San Juan National Forest surveyed its rivers during a 2007 update to its management plan, as stipulated by the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, it identified about 20 stream segments in the 1.8 million-acre forest as preliminarily suitable for designation. The Alliance quickly recognized that to succeed in protecting the segments for the values noted, the forest—and any legislator willing to carry a bill to place a stream on the federal registry—would need to win public support. The Alliance approached the Southwestern Water Conservation District, which is charged with protecting regional water resources for human utilization, to initiate collaborative conversations about the best ways to protect these streams while striking a balance with future water development interests.

That sparked what became a series of river protection workgroups, focused on discussing the myriad values on a handful of the Forest Service’s preliminarily suitable stream segments, with emphasis on finding protection mechanisms without the all-or-nothing approach. “We’re avoiding tunnel vision about Wild and Scenic,” says the Alliance’s Wendy McDermott. “This is a much broader discussion.”

The fact that Wild and Scenic designation has historically come with a federal reserved water right, which would be junior, or subordinate, to existing developed rights, has those looking to protect water resources for future human consumption concerned. “We assume that all water remaining to be developed would be claimed by a federal reserved water right,” says Steve Fearn, who represents the Southwestern Water Conservation District on the workgroups’ steering committee. In addition, the designation could prohibit development of structures or the firming of conditional water rights if they would adversely impact the identified values.

“You have this incredible beauty and array of natural values, and a need to look at water planning and development for the future and then you throw in all the other values—melting that into something that can work for all the people…it’s an art and a science, it doesn’t just happen.” – Marsha PorterNorton

The workgroups, the first of which convened in 2008, have drawn a broad spectrum of interested parties, from ranchers, landowners, conservationists and professional water experts to public lands officials, outfitters and water development interests. In addition to the ORVs identified by the Forest Service, the groups have extended their consideration of values to include social and economic. Groups are operating by consensus, which does not mean everyone agrees with the outcome but that they can support it. “You have this incredible beauty and array of natural values,” says Marsha PorterNorton, who coordinates the whole project and facilitates three of the workgroups, “and a need to look at water planning and development for the future and then you throw in all the other values—melting that into something that can work for all the people…it’s an art and a science, it doesn’t just happen.”

In 2013, a regional discussion, led by the steering committee, will evaluate the five workgroups’ proposals and attempt to craft a regional approach to protecting natural values while allowing water development to continue. “Participants may decide to support Wild and Scenic on one river and release suitability on another,” says McDermott, who is also on the steering committee.

According to forest supervisor Mark Stiles, the groups’ recommendations will inform decision-making, but in the end, it will be up to the Forest Service to determine whether segments will remain suitable for designation. Suitable segments will receive protective management to ensure they retain the characteristics that won them that status until Congress designates a segment Wild and Scenic or the Forest Service conducts its next update. The last revision was in 1983.

Print

Print