Those working to repair damage done to Warm Springs Fen shy away from the term “restoration” when discussing their efforts.

A 198-acre groundwater-fed wetland in central Colorado’s South Park, Warm Springs was mostly intact when it was protected about 10 years ago. An irrigation ditch cut through a small portion of the fen, intercepting shallow groundwater needed to support the wetland. But only 11 acres, which had been mined for peat, to be used as a soil amendment, were severely degraded.

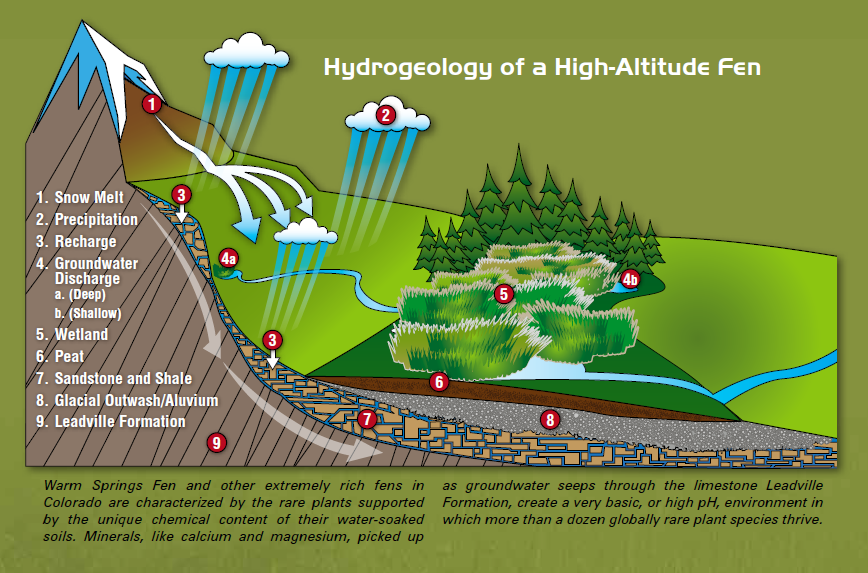

Still, claiming that the fen could be restored on a human time scale would be disingenuous. Fens like Warm Springs, which are found only in a few spots worldwide, contain thick seams of peat formed by plants decomposing in saturated soil over thousands of years. Peat formation can’t be sped up or engineered. So for now, rehabilitation is the best conservationists can hope for.

It may not sound like a lofty goal, but rehabilitating ancient landscapes like Warm Springs Fen is a complex undertaking, and the science guiding such efforts is still young. The payoff, however—to people, plants and wildlife—can be significant. South Park’s fens are valuable habitat for a few globally rare plants and insects. The fens help keep South Park’s trout fisheries—some of Colorado’s best—healthy by filtering pollutants in storm runoff, precipitation and groundwater that feeds headwater streams, and by providing nursery habitat for some trout species. And that helps prop up the local economy, of which tourism is a lynchpin.

The Geneva Creek iron fen. Photo By: Joe Rocchio

Wetlands are not the charismatic rock and ice landscapes that Colorado is best known for. Their looks are humble by comparison: water-soaked soils sprouting cattails and grasses. But the mere existence of rare fens in South Park helped win the basin designation as a National Heritage Area in 2009. The title is expected to be a boon to tourism and makes Park County eligible for up to $10 million in federal grants to protect natural and cultural resources.

Even in Colorado, where the best available mapping shows wetlands cover less than 2 percent of the state, these landscapes are ecological heavyweights. In southwestern Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, high altitude fens—often described as old-growth wetlands—are important carbon sinks and water storage sites. Along rivers and streams in lower lying areas, wetlands filter toxins and contaminants, promote groundwater recharge, and act as sponges that moderate flows, preventing floods during spring snowmelt and summer monsoons and releasing water slowly through the year. In mountains and valleys throughout the state, they’re wildlife hotspots.

A sloping fen along Trout Creek. Photo By: Joe Rocchio

“[Colorado’s wetlands] are not as extensive as wetlands in some parts of the country,” says Joanna Lemly, an ecologist with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, who has spent the last few years meticulously inventorying the state’s wetlands. “But that’s in some ways why they’re even more important here—because everything depends on water.”

But for years little effort was made to tread lightly on these sensitive landscapes. Before the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972, wetlands were freely dredged and filled to allow development or agricultural cultivation. In western states, dams, irrigation diversions and other alterations to natural hydrology have also taken a toll. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that more than half of wetlands nationwide have been lost since European settlement. Colorado is thought to have lost about the same percentage.

After 1972, though, wetlands on public and private land became regulated landscapes. Section 404 of the Clean Water Act requires developers to avoid, minimize and compensate for impacts to wetlands. And in 1989, the first President Bush upped the ante, setting a “no net loss” policy for wetlands at the federal level.

High Creek Fen, which is an extremely rich fen like Warm Springs, all fens pictured found in the Rocky Mountains. Photo By: Joe Rocchio

A number of tools have since emerged to meet that nationwide goal, though it remains elusive. The compensation method preferred by developers and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the agency responsible for issuing 404 permits, is a market-based approach called mitigation banking. Developers basically outsource their legal responsibility to replace what they destroy to third-party conservation banks, which create, restore or protect wetlands. The banks sell mitigation credits to developers, who use them to offset damage to other wetlands.

Since the late 1980s, more than 950 wetland and stream banks have protected and restored some 960,000 acres of habitat nationwide, according to the National Mitigation Banking Association. The Corps and the Environmental Protection Agency say that bank projects “typically involve larger, more ecologically valuable parcels, and more rigorous scientific and technical analysis,” than those undertaken by developers themselves.

But banking is an imperfect system. Certain types of wetlands, like the ancient fens found in South Park, are virtually irreplaceable. And other engineered wetlands often can’t provide the suite of services natural systems do. In a 2001 report, the National Research Council criticized federal regulators for not doing enough to ensure that lost functions were actually replaced, noting that monitoring was lackluster.

Gene Reetz, who retired after spending 25 years with the EPA’s wetland program, says the agency would often recommend more than one-for-one replacement—as in the “no net loss” approach—in recognition that what is created will not make up for what is lost. “Even that often leads to a net loss in function,” says Reetz. And proximity can be another problem. The EPA promotes on-site mitigation, where wetland values are replaced as near as possible to where they are lost. “The emphasis, at minimum, is to do it within the same watershed,” says Reetz. Still, the original community doesn’t recoup the lost ecologic functions and benefits.

Replacement value is also not quickly realized. In Colorado, it takes an average of 13 years for a created wetland to function comparably to a native one, according to a 2004 report published in Ecological Economics that attempted to quantify societal losses incurred during that “lag-time.”

The Warm Springs Fen in South Park, however, is protected by a mitigation bank that is a model for avoiding some of the pitfalls inherent in the practice. By restoring the hydrology of an existing wetland, rather than starting from scratch, it has greater potential for effectiveness. Once the bank sells all of its 20 credits (the majority have yet to become available), it will divest its interest in the land to The Nature Conservancy, which has pitched in by purchasing easements and water rights on surrounding properties. To fund the ongoing restoration work that’s needed, 10 percent of the variable, market-driven purchase price for each credit sold by the bank goes into a stewardship fund. “There are lots of wetlands that were mitigation-created, and they look okay for four or five years. But then they go to hell,” says Terri Schulz, director of landscape science and management for The Nature Conservancy’s Colorado chapter. Her group will be responsible for long-term management of the fen, using the endowment to control marauding invasive weed species.

At the federal level, the Corps and EPA responded to criticism with new mitigation rules, finalized in 2008. They will soon break ground on four demonstration projects—one on Colorado’s Front Range—to develop strategies for locating mitigation projects to maximize benefits to entire watersheds.

In the meantime, some local governments, including the city of Boulder, have stepped up to fill the gaps in federal law. “A lot of streams in the area don’t have water running in them year round,” says Katie Knapp, floodplain and wetland administrator for Boulder. Wetlands fed by ephemeral streams “don’t actually develop hydric soils, so the Corps wouldn’t map them as wetlands. But they still provide important habitat and are important for water quality.” Boulder’s regulations cover a broader range of wetlands and buffer areas than the Corps’, require on-site mitigation whenever possible, and prefer existing wetlands be expanded. Creating entirely new wetlands “can be kind of tricky in terms of hydrology,” Knapp says. “You don’t always get the creation you were after.”

“[Colorado’s wetlands] are not as extensive as wetlands in some parts of the country. But that’s in some ways why they’re even more important here—because everything depends on water.” – Joanna Lemly

While Boulder is focused on protecting what it has left, in the Fountain Creek Watershed, efforts are underway to increase wetland cover. The watershed, which drains a 927-square-mile area from El Paso County’s northern border to Pueblo, maxed-out its surface water supply more than 100 years ago. Today, about 80 percent of the water needed to quench Colorado Springs, Pueblo and Aurora is piped in from the Colorado River or deep aquifers in the Denver Basin. The result is a system out of balance: the watershed supports more water than it would under natural conditions. And that makes its streams flood prone.

“The old engineering standard was to narrow the stream, line it with concrete and get the water out of town,” says Carol Baker, an engineer and wetlands specialist with Colorado Springs Utilities. “But there were more flooding issues and more problems. We thought we were smarter than Mother Nature, but we kind of figured out, maybe not.”

Colorado Springs Utilities and the Lower Arkansas Water Conservancy District broke ground on a pilot flood reduction project this past fall behind a Walmart in Pueblo, where an off-channel detention pond and wetland will be constructed. The system will never be natural, per se; with all the imported water in Fountain Creek, the area will likely see a net increase in wetlands compared to historic conditions. But as a tool to reduce the creek’s base and peak flows and perhaps improve water quality in a watershed plagued by selenium pollution, wetlands, says Baker, “are like Mother Nature’s perfect little inventions.”

Print

Print