Colorado’s farm water use remains stubbornly high, according to a new report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, despite millions of dollars spent on experimental water-saving programs and a statewide push to conserve water.

Farm water is critical to Colorado’s effort to balance a growing population with a water system stressed by drought and climate change. Farmers are the largest users of water in Colorado and other Western states. In Colorado, growers use about 89 percent of available supplies, according to the Colorado Water Plan, while cites and industry consume roughly 11 percent.

State water officials and environmentalists have long called for finding ways to use less water on farms as one way to make Colorado’s drought- and growth-pressured supplies go further.

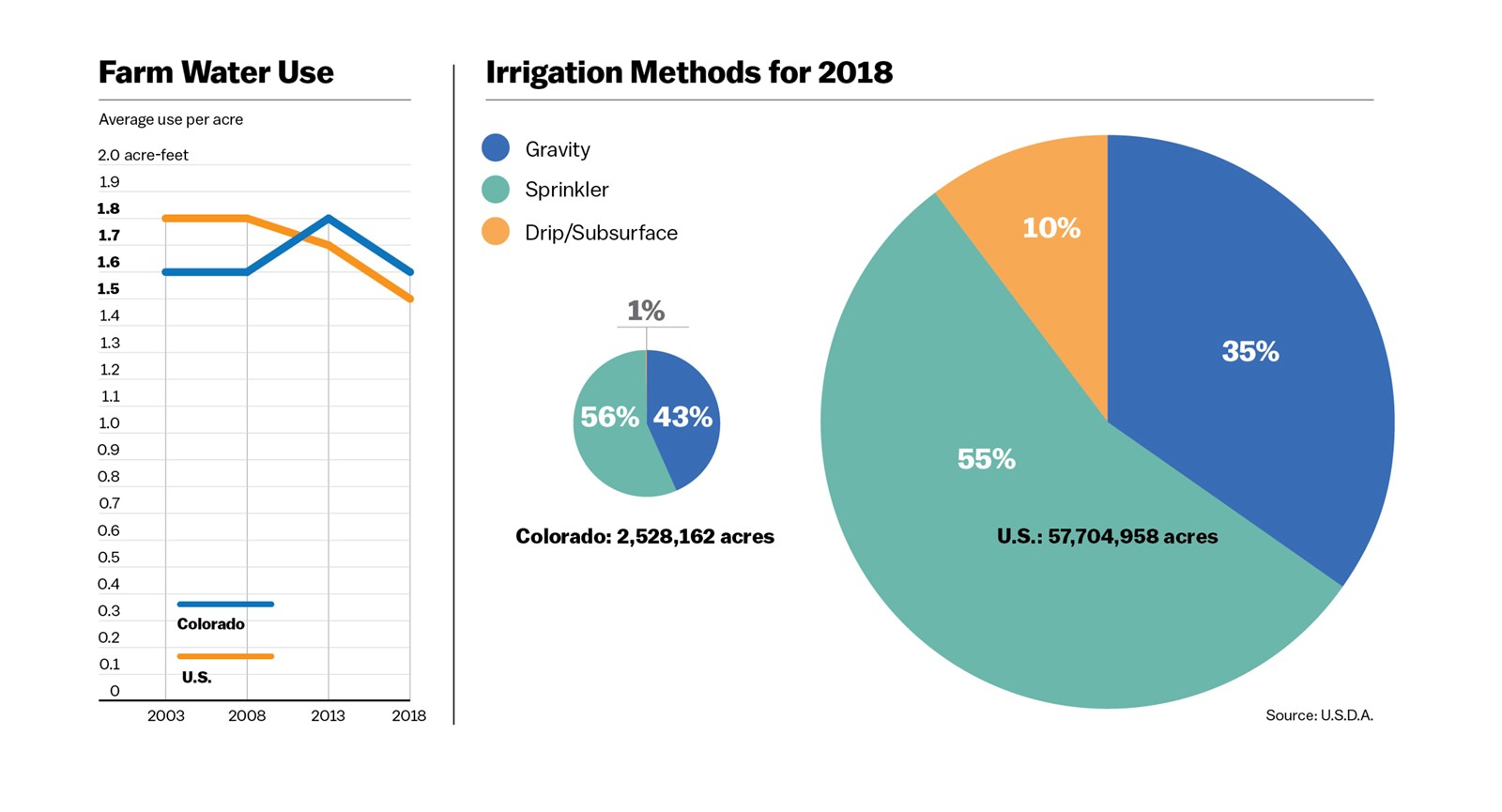

Although some individual operations are finding success in improving water efficiency, the new report shows little progress has been made on a statewide level. While the national average has gone steadily down since 2003, Colorado’s ag water use has not changed, remaining almost exactly where it was 17 years ago, according to the USDA’s Irrigation and Water Management Survey, which is conducted every five years.

Colorado growers applied an average of 1.6 acre-feet of water per acre in 2018, according to the USDA, slightly above the 1.5 acre-foot-per-acre average nationwide.

Colorado River Basin States Average 2018 Farm Water Use:

Arizona: 4.7 acre-feet per acre

California: 2.9 acre-feet per acre

Colorado: 1.6 acre-feet per acre

Nevada: 2.8 acre-feet per acre

New Mexico: 2.0 acre-feet per acre

Utah: 2.0 acre-feet per acre

Wyoming: 1.5 acre-feet per acre

Bill Meyer, Colorado director of the USDA program that produces the survey, said it wasn’t clear why the numbers aren’t showing a reduction. “You would assume that with better technologies and farming practices that it would have gone down.”

A complex beast

But Colorado Agriculture Commissioner Kate Greenberg said the USDA report doesn’t capture the layered realities of Western water.

“These surveys and charts don’t tell the whole story,” Greenberg said. “It’s an incredibly complex beast, both from the legal and hydrologic perspective.”

The new report comes at the same time Colorado cities, such as Denver, have become remarkably savvy in cutting water use, saving more than 20 percent in the last decade. They’ve done this largely by shrinking lawns, offering incentives to use water-saving plants, and enacting price increases, strategies that are largely unavailable to farmers.

The new report comes at the same time Colorado cities, such as Denver, have become remarkably savvy in cutting water use, saving more than 20 percent in the last decade. They’ve done this largely by shrinking lawns, offering incentives to use water-saving plants, and enacting price increases, strategies that are largely unavailable to farmers.

And Colorado isn’t the only state struggling.

Seven arid states comprise the Colorado River Basin—Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California—and all exceed the national average for farm water use, with the exception of Wyoming, which uses 1.5 acre-feet of water per acre, in line with the national average.

While it comes as no surprise that arid states would use more water than rain-rich states like Nebraska and Missouri, it doesn’t make the problem any less urgent, water officials said.

The pressure is on

Water managers are well aware of the public call for conservation.

“There is no doubt that with climate change and urbanization, the pressure is on [to reduce the use of] ag water,” said Aaron Derwingson, a farm water expert with The Nature Conservancy’s Colorado River Project. “A lot of people are saying, ‘If ag got more efficient we wouldn’t have [these looming shortages] this problem.’

“There is no question that ag needs to be a part of the solution, but we have to be thoughtful about how we do that….we need to think about a broader set of solutions,” Derwingson said. “This [notion of doing a] cut across the board may not meet our goals when we think what we really want Colorado to look like.”

Numerous programs are aimed at further improving farm water efficiency and conserving water that could eventually be freed up to share with cities or to benefit the environment while preserving farm economies.

Farmers also see benefits to their own operations by increasing on-field efficiency. Derek White Heckman farms 1,200 acres near Lamar in southeastern Colorado. In an effort to better manage his water, he is experimenting with cover crops, which when grown after a major crop such as corn is harvested help boost soil nutrients and, equally important, help keep moisture in the soil. Because rain is so scarce in this region, he’s willing to try almost anything to make sure he uses every drop of water that comes through his irrigation ditch.

And none of the work is easy, Greenberg said.

“Producers have been making progress in using new efficient technologies, but just because they are getting more efficient, doesn’t mean that they are going to divert less,” Greenberg said. “The legal liability for water right holders is that if they don’t use the full amount, they risk losing it.”

She is referring to Colorado’s prior appropriation system, in which the right to use water can be maintained only if it continues to be put to beneficial use. Water rights are subject to complex quantification analyses in the event of a transfer or sale. Although the only part of the water right that is transferable is the part that is technically “consumed” to grow the crop, much misconception remains around the notion of “use it or lose it.” Farmers who divert less, as they’re being encouraged to do, often don’t, because they fear losing their full water right, Greenberg said.

Ancient v. modern irrigation

Decades ago, the majority of Colorado farm fields were watered using flood irrigation, a simple, but labor-intensive method that fills field furrows with water to saturate adjacent rows. It is considered only 50 percent efficient. Today, less than half of those fields are watered using flood irrigation, with the majority now using a much more efficient technology that sprinkles fields, allowing water to be applied more precisely and reducing evaporation, according to the USDA report.

An irrigation system known as a center pivot sprinkler sits in a field near Longmont, Colo. The systems have helped Colorado use its farm water more efficiently, but state use still exceeds the national average. Credit: Jerd Smith

Still, the most modern, efficient systems for irrigating crops, subsurface or drip irrigation, are used on fewer than 1 percent of Colorado fields, according to the USDA, in part because they are much more expensive than traditional methods and because they don’t fit well with Colorado’s crop mix.

Nationwide roughly 10 percent of farm fields use these modern systems, according to the USDA survey.

Drip systems work best with high-dollar crops, such as vegetables, which comprise a small portion of Colorado’s farm economy.

Pricey upgrades

The vast majority of Colorado farmers grow corn, wheat and hay, whose low commodity prices don’t justify pricey high-tech watering technologies, Greenberg said.

Installation of one sprinkler system, for instance, can cost $700 per acre, while a subsurface drip irrigation system can cost nearly twice that amount, at $1,331, according to research done at Kansas State University.

The lack of progress frustrates farm conservation experts. They say that changes to Colorado’s laws to remove conservation disincentives may be needed as well as more funding to modernize farm ditches and diversion structures.

“It’s a tough situation,” said Joel Schneekloth, regional water resource specialist with the Colorado State University Extension Service.

Finding just enough

Colorado’s scenic, historic irrigation ditches lose significant amounts of water to seepage and evaporation, some of which actually enhances wildlife habitat and streams and helps ensure farmers downstream have enough water (via return flows) to fulfill their own water rights.

“It takes a certain amount of water just to run a canal system,” Schneekloth said. “Often you can’t reduce that amount unless you line the canals, but then you run into reduced return flows farther downstream.”

“We would like to get to a point where we are putting on just enough water, but not excess water,” Schneekloth said.

Clint Evans is Colorado State Conservationist with the USDA. His agency spent $45 million in 2019 on some 600 farm water conservation projects, all with the hope of helping Colorado farmers use their water more efficiently. And the projects have shown some success.

One project in the Grand Valley has lined and piped miles of irrigation ditches, allowing some 30,000 acre-feet of previously diverted water to remain in the Colorado River.

Still, given the vast amounts of water used, these small programs have yet to move the needle significantly, according to the report.

Food or development?

Even as Colorado considers new ways to conserve farm water, some fear that across-the-board cuts in farm water use could cripple local farm economies, hurt streams and wetlands that have come to rely on the excess water that flows off of irrigated fields, and eventually limit Colorado’s ability to grow food.

“The most common way I’ve seen the narrative framed is, ‘If ag uses 80 percent of the water, and we could get that down to 70 percent, the Front Range could grow [urbanize] as much as it wants,” Greenberg said, “meaning that growth has a greater value than water used in farming.

“What we could choose to say, instead, is that we value our farmers and ranchers, and we value being able to produce our own food just as much as the rampant development that is gobbling up ag land and ag water,” Greenberg said.

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News. She can be reached at 720-398-6474, via email at jerd@wateredco.org or @jerd_smith.

Fresh Water News is an independent, non-partisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.

Correction: Colorado ag uses 89 percent of available water statewide. In addition, Aaron Derwingson’s perspective on the complexities of conserving agricultural water in Colorado has been clarified.

Print

Print