Below-average snowpack, minimal spring precipitation, and record-breaking March heat set the stage for a devastating 2012 fire season across Colorado.

The High Park Fire tore through the canyons and valleys northwest of Fort Collins in June, burning 87,000 acres and destroying 259 homes. Just weeks later, the Waldo Canyon Fire outside Colorado Springs became the most destructive fire in Colorado history, burning 347 homes before firefighters and rain contained it in early July. As of mid-August, 1,242 fires had burned more than 231,000 acres statewide.

“The dry and warm conditions allowed fuels to dry out several weeks ahead of schedule. In March, we were thinking this could be ugly,” says Tim Mathewson, a meteorologist with the Lakewood-based Rocky Mountain Coordination Center, which facilitates wildfire response in Colorado, Wyoming and other states.

The last year in which spring snowpack was so dramatically low was 2002, the year of the Hayman Fire—the state’s largest fire on record. That year, 4,600 fires scorched nearly 620,000 acres, far outstripping the 2012 totals. Projections for next year’s fire season will not be made until spring 2013, and will largely depend once again on winter snowpack and spring conditions. However, the rust-red trees that are the telltale sign of mountain pine beetle kill across the Rockies have raised future fire risk for many communities. Under the right conditions, many of the beetle kill forests will be primed for large, intense fires.

On the bright side, Mathewson notes the current transition from a La Niña to an El Niño cycle. While La Niña typically brings drier conditions to Colorado, El Niño, though a little more unpredictable, normally results in wetter summer conditions. This is true especially in the southeastern corner of the state—which could provide some relief to a region hammered by drought now for two years running.

After the Burn

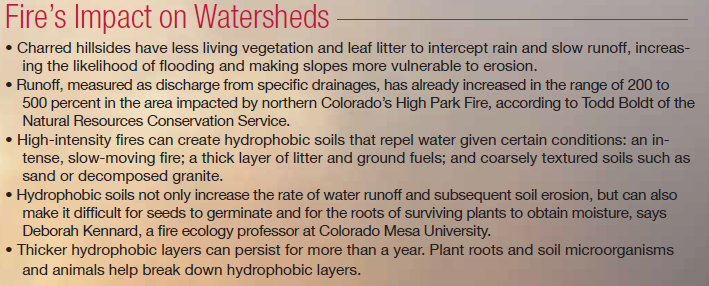

In the aftermath of the 2012 fire season, water and land managers are scrambling to minimize the impacts to watersheds. Sediment-loading of water supplies for drinking and irrigation is one of the biggest post-fire concerns. Flooding and debris flows—fast-moving mixtures of rock, mud and vegetation down steep slopes—could also damage roads, bridges, culverts, and even homes and other structures.

Todd Boldt, district conservationist for the Natural Resources Conservation Service, has been coordinating mitigation efforts in response to the

Flames ignite on the north side of the Poudre Canyon, just below the Grey Rock trailhead, on May 14, the first

day of the High Park Fire. On July 7, heavy rains washed ash and debris from the High Park Fire into the Poudre

River, causing mudslides. Photo By: Doug Canarroe

High Park Fire. Together with other government agencies, he is working to mulch and seed around 5,600 acres in drainages hit by the most severe fire. Such treatments can reduce runoff and sedimentation by 20 percent. The work isn’t cheap—initial costs for mulching and seeding on Forest Service land have been around $7 million, with another $17 million in mitigation measures identified, including mulching and seeding private land, installing flood diversion structures, and repairing roads.

Flames ignite on the north side of the Poudre Canyon, just below the Grey Rock trailhead, on May 14, the first day of the High Park Fire. On July 7, heavy rains washed ash and debris from the High Park Fire into the Poudre River, killing fish. Photo By: Doug Conarroe

Officials handling the post-fire response to the Waldo Canyon Fire outside of Colorado Springs are similarly concerned about the lack of vegetation cover on uplands. Peak flows are expected to be three to four times above average in drainages that suffered moderate- or high-severity fire, and the amounts of sediment and debris moving downstream could be substantial.

Steven Sanchez, soil and water program manager for the Pike and San Isabel National Forests, says the experience gained from restoring watersheds after the 2002 Hayman Fire will result in a more effective response to the Waldo Canyon Fire, because the two occurred on similar, highly erodible soils. “We have learned that you have to quickly get ground cover in place to hold it together,” says Sanchez. The Forest Service is applying mulch to over 3,000 acres, prioritizing headwaters regions, fishery and wildlife habitat, and other sensitive and high value areas in the for est.

Meanwhile, Colorado Springs Utilities is working to install sediment basins and in-stream structures to trap sediments, slow runoff and reduce erosion in important drainages.

Print

Print