The quest to find solutions on the Colorado River may require that each state and nation, water user and conservation group stand together for the benefit of all. So, are we in this together?

On a hot summer evening in July 2015, Perry Cabot is driving on a country highway outside Montrose. He’s just finished another day of fieldwork and is heading back to his office in Grand Junction, on Colorado’s sparsely populated Western Slope.

Cabot is an engineer and a scientist. Working for the Colorado Water Institute and Colorado State University Extension, his quest over the next several years is to enumerate a very important set of trends. If he succeeds, he will contribute critical information to the discussion among a growing cadre of people in the Colorado River Basin, including farmers, environmentalists, engineers, hydrologists, plant and fish experts, policy makers and politicians. All are helping lead the way into a 21st-century world where the river delivers its own budget and everyone, from the farmers outside Montrose to the city folk in Los Angeles, is able to live with what it has to offer.

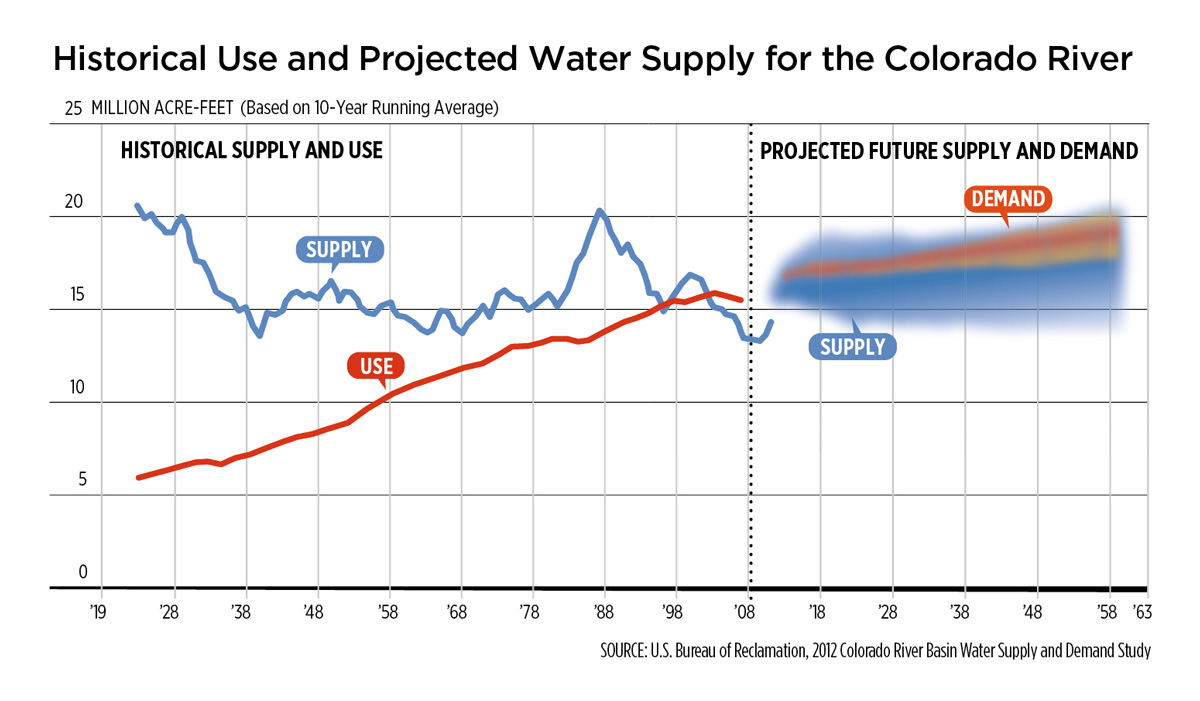

That means doing more with less, and Cabot is all about that. He and hundreds of experts across the nine states (two in Mexico) that make up the basin know that the days when the river could be overused are over. His challenge is to establish the numbers that show how much water can be conserved in any given farm field, while maintaining a positive economic yield for farmers. Though some changes to state water law would likely be required first, the conserved water could in theory be transferred somewhere else in the river basin to help make up a system-wide shortfall expected to reach millions of acre-feet per year by 2060, while at the same time creating ecologic benefits in vulnerable river stretches and providing increased security against interstate compact-induced shortages.

Farmers who succeed at maintaining healthy harvests with less water—through practices such as deficit irrigation or partial-season irrigation—could eventually be paid handsomely for their efforts by water utilities and others who hold more junior water rights and face greater risk in times of shortage. But first the science and engineering must be done. “It’s a careful balancing act,” Cabot says.

Studies such as those Cabot is conducting are among an array of efforts across the basin to find new tools for managing a river in perpetual overdraft. While states have shown an increasingly cooperative stance, questions remain about their commitments to sharing the numerous risks and uncertainties that exist.

“It’s getting harder,” says Jennifer Gimbel, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s principal deputy assistant secretary for water and science. “Mother Nature gave us a break this year, but we still have the effects of a long-term drought to deal with. We have to step back and see if there are other ways to deal with the risks.”

In the past, water crises prompted policy makers and politicians to look to the courts to examine and enforce the set of legal agreements that constitute the “Law of the River,” including the rules of the 1922 Colorado River Compact, in order to resolve conflicts and solve problems. While some still believe the courts could help lead the river into the 21st century, those who manage its supplies every day have instead turned to negotiated agreements to address tough issues outside of court.

There has always been conflict on the river—between the United States and Mexico, between the lower basin and upper basin states of the U.S., and also within basins—but there is growing agreement that the futures of each state and nation that shares the river are inextricably linked. Even as attempts are made to re-balance risk, along with who shoulders the brunt of it, many agree that engaging the courts would only introduce greater risk: the risk of a ruling even less desirable than the constructs of the current system.

For one, court actions rarely involve consensus building and could threaten to unravel years of more diplomatic problem solving. Additionally, the process to challenge the laws at the U.S. Supreme Court would take years and perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars that could be better spent elsewhere, says Eric Kuhn, general manager of the Glenwood Springs, Colorado-based Colorado River Water Conservation District. “I don’t see amending the compact or suing under the compact as being possible. And I really don’t see what it would accomplish. The issue is that there is less water and courts can’t make water.”

Despite these ongoing tensions, users of the river—driven by the unyielding nature of the drought and the specter of climate change—are learning new ways of operating storage and diversion systems and altering use patterns to, in essence, create more water via collaboration.

Perry Cabot walks one of his research fields.

Photo by Barton Glasser

A Re-Calibration of Risk Sharing

Every major user on the river understands who faces the most risk right now. Because of agreements forged in the late 1960s when Arizona campaigned to build its Central Arizona Project, which delivers more than half of its Colorado River apportionment, it has a subordinated water right. Under the Law of the River, Central Arizona Project water users could practically go dry before California’s share of lower basin water would be affected.

Though Nevada also is at high risk, it takes a much smaller amount of water out of the river—just 300,000 acre-feet or 4 percent of the lower basin’s annual share. To reduce its risk, Las Vegas, the primary user of Nevada’s Colorado River water, has moved the fastest, by some accounts, to drastically reduce water use and to build $1.5 billion worth of new diversion structures at Lake Mead that will allow it to pump water out even if the lake drops below the 1,000-foot elevation critical for its existing intake pipes. Even if Lake Mead falls again next year to 1,075 feet above sea level, where Nevada would have to give up 20,000 acre-feet of water under the 2007 Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and the Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead, Las Vegas could absorb the hit, says John Entsminger, manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. As Las Vegas’ water provider, the authority says its customers only used about 225,000 acre-feet this year, 30 percent less than a decade ago. “Our community is positioned to absorb these reductions without having to take any drastic measures such as water rationing,” Entsminger says.

In the upper basin, risk seems farther away, but just as potent, as it affects decisions currently being made about the way states will provide water for growing communities and industries. The four upper basin states currently use roughly 60 percent of their 7.5 million acre-foot annual Colorado River Compact-allotted share, which would seemingly leave them plenty of room to grow. But as the Colorado River’s flows trend downward, they risk being unable to meet the terms of the compact, which in the absence of cooperative agreements obligates them to ensure the lower basin receives its full allotment by releasing water from their upstream reservoirs—and, if it came to it, foregoing their own uses.

For everyone, the hunt is on, not just for new technologies and money to pay for conservation, but for ways to ensure that risks are shared and that no one state or city faces draconian water rationing or even a shutoff.

“We can’t have anybody taking all of the risk,” says Gimbel. “Risk sharing and cooperation is the only way to get through these challenges. California could sit back and say, ‘we’re the senior water right on the river and therefore we don’t have to take any losses.’ And while they—and everyone—could simply rest on their legal rights, that’s not the approach we’ve used to tackle problems on the Colorado.”

Among the major consensus-based agreements that have been crafted are the Interim Guidelines of 2007. These dictated that Lake Powell and Lake Mead, until then managed for the most part independently of one another for the benefit of the upper and lower basin states respectively, would be managed jointly. The 2007 guidelines also established an “Intentionally Created Surplus” program, where lower basin states could shore up credits in Lake Mead of up to 2.1 million acre-feet of water through implementing practices such as lining canals, fallowing and desalination. This was also one of the first times Arizona and Nevada agreed to share shortages.

Then, in 2012 the United States and Mexico reached a five-year agreement known as Minute 319. Here, Mexico agreed to take a reduction in its water deliveries at the same critical Lake Mead elevations that would trigger Arizona and Nevada to cut back. In exchange, Mexico gained the right to store water in U.S. facilities, as well as the right to share in any surpluses, plus money toward conservation programs.

As a result of the agreement, Mexico and a coalition of major conservation groups such as The Nature Conservancy and the Environmental Defense Fund, among others, gained the ability to arrange for a pulse flow for the Colorado River delta at the Gulf of California, which has not received consistent flows since the 1960s. Despite some wet years in the 1980s, the delta has remained one of the most at-risk ecosystems on the river. Both Mexico and the United States provided water for the flow, and the NGOs, including the Mexican conservation group Pronatura Noroeste, contributed one-third of the water.

Out of international necessity, the federal government has been the lead negotiator in most of the critical talks with Mexico. It is also helping guide the next round of talks that river users hope will lead to an extension of Minute 319, or another successor agreement, to continue the critical work of sharing shortages while ensuring badly needed environmental water supplies. Minute 319 is currently set to expire in 2017.

How much more the federal government can or is willing to do to help modernize river management isn’t clear. And states differ in their views of what the federal government should be doing. But few question that it was then-U.S. Interior Secretary Gale Norton’s public threat to intervene that helped drive the creation of the Interim Guidelines in 2007. And the federal government in the past five years has proven willing to add cash to the pot to help move important conservation programs forward. The $3 million it has pledged to a multi-jurisdictional agreement to pilot test market-based conservation programs in the basin was the largest contribution among the participants, which include some of the most powerful entities on the river. Together, the five parties to the agreement—the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the Central Arizona Project, the Southern Nevada Water Authority, Denver Water and the U.S Bureau of Reclamation—agreed to ante up $11 million to evaluate ways to stabilize the system so that no one will have to be involuntarily rationed.

Though most believe it will take much more than $11 million to fix the overdraft on the Colorado River—for perspective, the Australian government has authorized several billion dollars to implement water-saving programs in the Murray-Darling Basin, a river that shares many similarities with the Colorado—the investment toward reducing consumption is considered an important step that could lead to a scaled-up approach.

Risk Reduction via Conservation and Water “Banking”

It’s no wonder city utilities are paying in to such a program. In Arizona, Nevada, California and Colorado, cities have some of the most junior water rights. As a result, under the current system of laws crafted decades ago, they are most at risk of losing access to water in a depleted system.

At the same time, cities have the most money and political clout of any entity on the river, meaning that, ultimately, a political fix to ensure they get the water they need would likely be found should such shortages occur. In that respect, some experts contend, urbanites have less to worry about than any of the river’s other users.

“It is the river itself—its ecosystems and its critters—that are most at risk,” says Kuhn. “They have the least political power. Next are the farmers. They have the most senior rights, but less political power and money. And the least at risk in the long term are the municipalities, because they have [politically powerful] voters and the money.”

But that doesn’t mean the cities aren’t concerned. Denver Water’s largest storage vessel, Dillon Reservoir, sits in the middle of resort country in Colorado’s mountains. It has water rights that date back only to the 1950s. These rights are so junior that the utility could have to forego use of nearly all of its Colorado River supplies if necessary to ensure the lower basin states receive their legally allotted supplies during a system-wide water shortage.

Similarly, Phoenix, Las Vegas and the water supply entities constituting the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California could face cut-offs. Though these powerful entities don’t agree on everything, they have signed on to several collaborative conservation efforts that show early promise in reducing agricultural consumptive water use. They see this as a way to secure additional municipal water while balancing demand with the river’s available flows.

In Arizona, for instance, the Central Arizona Project is looking to pay farmers to forego use of some Colorado River water and use the cash to install new super-efficient irrigation systems. To help farmers cope in the interim, however, they’re tapping water that for years has been stored underground from past Colorado River diversions. And California over the past two decades has facilitated large-scale cooperative agreements between agricultural and municipal users in order to shave water use by nearly 20 percent and stay within its apportionment.

States are also contemplating increased establishment of water markets. The concept allows people to sell or lease water rights freely in a market where price is dictated by demand and the infrastructure exists to move the water easily. In the past, these have proven unpopular in the Colorado River Basin due to political constraints. In the upper basin, for instance, water managers have historically feared that if they agree to sell their water once, it could harm their future right to the water.

Advocates say water markets could help create more realistic pricing that reflects how much water actually costs, and will help distribute it to those who need it most—or are most willing to pay.

Such markets would be more likely to operate on an intrastate level. However, interstate markets are already operating in the lower basin, with a large deal inked in September 2015 between the Southern Nevada Water Authority and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which lost roughly half of its water supplies this year when the Sierra Nevada mountains saw almost no snow. Under the deal, the California district will pay $44.4 million to SNWA for the Las Vegas’ water provider to release 150,000 acre-feet of water it has stored in Lake Mead. That amounts to half of Nevada’s annual Colorado River share, but just 10 percent of the supplies the state has stored away, including through the Intentionally Created Surplus program in Mead. Under the agreement, SNWA maintains the option to pay California back and reclaim that water down the road, if needed.

A mechanism sometimes used to facilitate water marketing within a region is called a water bank. These structures can be physical, administrative or legal—or all three—but in concept they allow water to be saved by a water user in a stream system and then used for another purpose.

Colorado River flows through the Grand Canyon, which ferry more than 25,000 boaters each year, are dictated by releases from Glen Canyon Dam. Those releases are managed under the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program, established in 1997. Photo by Pete McBride

To work well, water banks must be located in regions where water can be transferred between participants. The water’s physical movement must be easily tracked. Ideally, they would be established on streams that need higher environmental flows—conservation groups assert this is key to optimizing such efforts—but also where reservoirs exist that can hold “banked” water until it is needed. And like financial institutions, water banks would need to generate some kind of revenue to cover the cost of operations and accounting. Successful water banking programs will also rely on new science and new farming methods to make water available, and then to transfer and store it in ways that adhere to the states’ and river’s existing laws.

In Colorado, The Nature Conservancy and four water agencies that have sometimes battled one another have contributed $300,000 to fund Cabot’s work for two years. It’s only a start. He needs three to five years of crop data to ensure the numbers he is deriving are reliable. This year, while increased spring precipitation in parts of the upper basin gave a positive boost to inflows at Lake Powell, it was a difficult year to test the impacts of reduced irrigation, says Cabot. “Typically, I would compare a field irrigated with the full amount of water used historically next to a field that we’ve applied less water to. This year, there was a lot of water in the early summer, so the differences are somewhat muted.”

After several more growing seasons, Cabot and his partners hope to show how much water the upper basin states can save and store in their reservoirs, such as Flaming Gorge in Wyoming and Utah or Blue Mesa in Colorado, to operate as an insurance plan for Lake Powell—a primary aim of their work. That stored water could be moved down to Powell when it looks as if the reservoir’s levels are going to drop precariously low, compromising its ability to time releases to the lower basin, generate power, and support environmental and recreational needs in the Grand Canyon below. If such efforts were unable to forestall a compact shortage, the bank would then serve as a sort of augmentation plan where users with pre-compact water rights would be paid to interrupt their use while those with junior water rights—mostly municipal and industrial users—would pay the bank to continue diverting.

Similarly, in the lower basin, water that is saved via new conservation initiatives among crop growers and others can be left in Lake Mead to forestall a shortage determination and bank surpluses for drier years ahead.

The Colorado, Re-Imagined

Somewhere in the system, users must find a way to reduce use by at least 600,000 to 1.2 million acre-feet—and soon. That level of savings is doable, according the Bureau of Reclamation, but would only be a start. It would help offset the structural deficit in the lower basin, but still wouldn’t provide more water for environmental restoration or to act as a cushion for growth in the upper basin or against further climate change.

Reclamation’s 2015 “Moving Forward” report, a follow-up to the agency’s 2012 Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study, stated that utilities basin-wide are planning 1.1 million acre-feet per year of water conservation and reuse by 2030. At the same time, they’ll face increased demands from growing populations.

Agricultural conservation efforts, already estimated to have “saved” 1 million acre-feet over recent decades, are trickier both to calculate and to sustain. Not only are producers wary of losing productive acreage and seeing rural economies decline, but past conservation efforts haven’t necessarily translated into more water in the system; rather, they’ve translated to increased yields using the same amount of water.

And this is why Cabot’s work to evaluate the potential of deficit and partial-season irrigation is critical, because the goal is to reduce actual consumptive use on farms and ranches across the Southwest without harming producers and rural communities. That will require ensuring mutual benefits—and sufficient payouts—to justly compensate farmers for their efforts.

Given the diversity of the basin’s states and their varying geographies, economies and laws, each will need to choose those methods that prove most effective, as well as economically and politically feasible.

Those concerned about the river’s own health say the states must continue to adopt modern management methods and regulations to protect flows and to better reflect the 21st-century values, such as river recreation and healthy ecosystems, that the people of the basin embrace.

From his perspective in the lower basin, Southern Nevada’s Entsminger believes a more collaborative era is emerging and gaining traction. “The Colorado River has continually redefined itself. This is not a new dialogue, but rather one that has evolved—and continues to progress—over time.”

Colorado River water users, faced with a growing water supply imbalance, have launched an $11 million, multi-state, multi-jurisdictional pilot project to experiment with aggressive conservation efforts and temporary water transfers that stretch available water. Since 2000, year after year with few exceptions, levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead have dropped. These massive reservoirs, once able to hold four years worth of water for 40 million people, are now just half full, and the downward trend shows no signs of easing.

The specter of disaster is real enough and close enough that four powerful water users and the federal government were able to reach an agreement in record time in mid-2014. Their innovative effort, called the Colorado River System Conservation Program, seeks to develop voluntary, market-based measures that reduce water demand based on modeling developed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. “The modeling shows it can be done,” says Jim Lochhead, general manager of Denver Water, the largest utility in Colorado and a funder of the program.

The working group, which includes Denver Water, the Upper Colorado River Commission, the Southern Nevada Water Authority, the Central Arizona Water Conservation District, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, is evaluating options to dramatically reduce water use. They need to persuade farmers, city utilities and large industrial users to voluntarily cut back in exchange for cash. The saved water would be used to help refill Powell and Mead and avoid future shortages.

But much of the work lies in developing precise and credible ways to measure how much water can be freed up through projects like deficit irrigation, and how saved water can be moved through the system without being inadvertently withdrawn by other users. In some cases, legislatures will have to amend existing laws or write new ones to allow water to be moved and stored differently.

Despite the challenges, each party has agreed to contribute cash toward pilot projects. Non-federal entities will contribute up to $2 million each, while the Bureau of Reclamation will contribute $3 million.

Pilot programs in the lower basin are being managed by Reclamation, while the Upper Colorado River Commission is overseeing pilot programs in the upper basin. Applications for individual projects are being evaluated and approved based on their cost-effectiveness per acre-foot of water saved, ease of verification, and geographic diversity. Each state and agency will continue to select the conservation measures most appropriate for its region and water users.

At least $2.75 million of the funding will be used for pilot projects in the upper basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. The first effort, in Colorado’s Yampa River Basin, began in July 2015. It entails splitting the hay irrigation season so that two hay cuttings instead of three are harvested. The experiment, on the historic Carpenter Ranch, means growers will get paid for the loss of that third cutting while the unused water will be kept in the system.

Lochhead and others believe this innovative approach will be an important proving ground for even more aggressive efforts to keep water in the river and its reservoirs. “It’s not agriculture. It’s not urban. It’s not environmental. It’s all the sectors in the basin working together.”

-Jerd Smith

Print

Print