Poke around in the annals of Colorado water history for long enough and you’ll find the name “Vidler” recurring with some frequency. It refers to a man, Rees Vidler, who purchased a silver mine southwest of Georgetown, Colorado, in 1902. The mine eventually became the Vidler Tunnel, which diverts water from the Colorado River watershed and moves it beneath the Continental Divide to the South Platte River Basin. It’s also shorthand for an important 1979 Colorado Supreme Court ruling, the Vidler decision, that sought to limit water speculation in the state.

And finally, there’s the Vidler Water Company. Its modern incarnation formed in 1995, when the Wall Street-connected company bought the tunnel that was named after the man and set about attempting to do what the Vidler decision explicitly tried to limit: investing in water rights with the hopes of returning substantial profits.

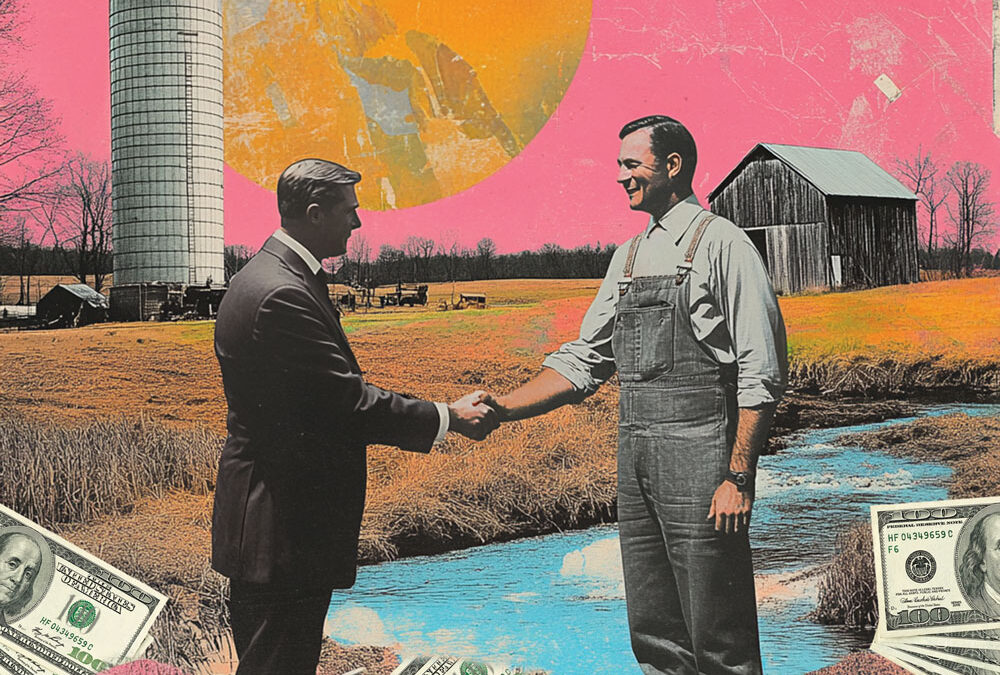

Kerry Donovan first heard about a hedge fund with ties to the Vidler Water Company, Water Asset Management (WAM), when she was purchasing hay from a farmer in Mack, Colorado, in 2019. Donovan runs a ranch near Edwards with water rights that date back to the 1800s, and at the time she was a state senator representing a district on Colorado’s West Slope. She was surprised to later learn that between 2017 and 2020 WAM had bought up $16.6 million worth of farmland in the Grand Valley near Grand Junction.

WAM’s spending spree was happening at the same time Donovan had been hearing more discussion about the creation of water mar-

kets, which “set the warning bells off” for her. “It really seemed like we were careening toward a place where water wasn’t going to be held

for beneficial use except for a benefit to the investors,” she says.

Donovan was not alone. Farmers and environmentalists alike have spoken out against Wall Street plays in rural agriculture. Top water negotiators in deep red states like Utah and blue states like Colorado have raised concerns about such investment.

Efforts of private investors to sell groundwater beneath productive agricultural lands in the San Luis Valley to Front Range cities have met backlash. The investors, a real estate development firm called Renewable Water Resources, purchased farmland in the valley and proposed exporting underlying groundwater to Douglas County, south of Denver — but RWR doesn’t have buyers for that water. In 2022 Douglas County rejected the idea of RWR’s export proposal. And in the water-short San Luis Valley, where irrigators are fallow-

ing farmland to combat shrinking aquifers, a coalition — including water districts, conservation districts, towns, cities and counties —

argues that taking water from the valley would threaten agriculture, the economy and the environment. An Alamosa Citizen poll found that only 1% of valley residents supported the plan to export water. “This valley was so heavily split in both the 2016 and 2020 elections,” says Teal Letho, an activist and water policy-focused social media influencer from Durango who posts under the name Western Water Girl. “For them to have such a unifying voice on this issue is a very resounding: ‘No, you’re not taking our water.’” Opposing water speculation, Letho says, can transcend “the Republican-Democrat dynamic.”

Despite the complexities of water law, often little context or explanation is needed to raise eyebrows about water investment. When CBS Mornings ran a 2023 investigative report on Wall Street’s interest in Western water, the host felt compelled to editorialize. Treating water as “the new oil,” he said, reminded him of “that scene in The Lorax when they start selling fresh air … very troubling stuff.”

The idea of private equity firms hoarding water during a drought and selling an essential resource to thirsty residents at a substantial

markup is, for many observers, a vision of dystopia. And for the agricultural community, there are worries about private investors playing a role in aggressive “buy and dry” schemes that have shut down farms across the West. Traditional buy and dry has already occurred without Wall Street involvement, when municipalities have purchased farmland and transferred agricultural water to city taps, hollowing out rural economies in places like Crowley and Bent counties in southeastern Colorado.

Wall Street, Donovan says, approaches water with its own set of priorities that could make the issue even worse. “If you’re a family-run ranch or farm, you’re not doing it because the hours are good,” she says. “You’re not doing it to get rich.” She contrasts that ethic with the goals of investment speculators. “That’s a really scary proposition for someone to hold water rights where their primary goal is to make money — not to raise food, not to fill up your bath-tub, but to make money.”

Anti-speculation restrictions are at the heart of water law in many arid states, including Colorado, but new forms of speculative water investment are difficult to define and prohibit. Recent efforts in Washington, D.C., and in the Colorado legislature to strengthen

anti-speculation laws, including several led by Donovan, have been unsuccessful. Water investors themselves argue that unleashing market forces on water management will modernize an inefficient and outdated system, assisting with water distribution in times of drought. They say this can be done while raking in returns. WAM president Matthew Diserio told Fast Company in 2023 that water is “the biggest emerging market on Earth,” calling it “a trillion-dollar market opportunity.”

Are critics’ concerns over the issue overblown? Or could average homeowners someday be subjected to surge pricing for tap water during droughts as farmlands dry up?

From the Colorado Doctrine to the Vidler Decision

When gold prospectors began flocking to the Colorado Territory in the mid-1800s, settlers from the East Coast quickly recognized that water was scarce in the region and that water diversion would be a key component of mining and farming operations.

The gold seekers — first in the codes of Colorado mining districts and later in the Colorado Constitution of 1876 — set up a legal system that was intended to speed settlement through the broad distribution of water rights. This set of laws, which was later adapted by other Western states, is known as the “Colorado Doctrine.” Legal scholar David Schorr argues that the doctrine was anti-speculative in its intent, and was based on the idea of “distributive justice” — Colorado water law intended for this vital public resource to be distributed to as many people as possible.

A driving question on settlers’ minds, Schorr writes, was: “Would the lands of the public domain be disposed of to absentee speculators

and corporations controlled by Eastern and European investors, or to the archetypal ‘actual settler’?” The Colorado Doctrine was developed in favor of the latter. The doctrine differentiates water from typical property rights, establishing that ownership of water belongs to the people of Colorado, but water rights allow the use of that water. It included two fundamental pieces of Western water law: the prior appropriation system (those with the oldest water rights have priority over junior water users) and beneficial use (water rights are obtained, not through buying stream-front property, but by diverting and using water for a specific purpose). The “use it or lose it” principle of water law further prevented speculation, hoarding and monopolization since it threatened the loss of water rights if beneficial use stopped. By dissuading wealthy water rights owners from sitting on water for years while waiting for its value to rise, the Colorado Doctrine encouraged Western development by European-Americans and the forced removal of Indigenous peoples. Boosters promoted the idea that anyone could strike it rich in Colorado with a lucky mining claim or the right amount of hard-scrabble effort poured into a ranch carved from the public domain.

By the time mining executive Rees Vidler bought his tunnel in the early 1900s, the Colorado Doctrine was thoroughly enshrined in state water law and development was proceeding apace. He didn’t own the Vidler Tunnel for long, and subsequent owners’ plans for the tunnel failed to materialize. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the tunnel found new life as a small transmountain diversion project owned by the Vidler Tunnel Water Company. In 1973, the company proposed building Sheephorn Reservoir on the upper mainstem of the Colorado River that would have been capable of storing over 150,000 acre-feet of water.

The Vidler Tunnel Water Company was a private company seeking to profit from a public resource, and its plan for Sheephorn Reservoir ran up against the anti-speculation intent of the Colorado Doctrine. The City of Golden was considering leasing a fraction of that water, but Vidler did not have buyers in place for the majority of the water that would be captured by the proposed project. The Colorado Supreme Court eventually ruled against Vidler’s proposal. “Our constitution,” the justices wrote in the 1979 decision, “guarantees a right to appropriate, not a right to speculate. The right to appropriate is for use, not merely for profit.”

Since the company had proposed the reservoir without specific plans to put the water to beneficial use, Sheephorn Reservoir was

stymied. It would take several decades for Vidler to once again emerge on the water scene.

A New Era

The Vidler Tunnel saw new ownership in 1995 when it was purchased by Disque Deane Jr. and Al Parker, two investors who believed betting on water was the future in the fast-growing Southwest. They started a new company with a familiar name, the Vidler Water Company, and began acquiring water rights primarily with the hopes of marketing them to Front Range cities.

Vidler merged with a real-estate firm in 2022. Its most notable (and controversial) projects are in Nevada, the driest state in the

country. Early Vidler partners moved on to other water investment firms and companies that have been purchasing water rights and assets across the West like Greenstone and Cadiz Inc. Many of these private investors wanted to do something that the Colorado Doctrine had intentionally avoided: open water pricing to market forces, generating returns for investors as the value of water rights increases. Water investment reports have concluded that doing so could reduce waste and inefficiencies that plague Western water, especially in agriculture. Some reports claim that prior appropriation and use-it-or-lose-it laws encourage water rights holders to take their full allotment of water, even when there are users elsewhere who are willing to pay more per gallon than the returns available from an alfalfa farm, for example.

Since agriculture uses around 89% of all water consumed in Colorado, and producers hold many senior water rights, farmers and ranchers are often seen as an obvious target for programs that conserve water, either for environmental streamflow purposes or for downstream users and interstate compact compliance.

Colorado’s population has more than doubled since the 1979 Vidler ruling. And the effects of climate change, that have been felt in the Colorado River Basin since the onset of the Millennium Drought in 2000, have reduced the river’s average flows by around 20% compared to the 20th century. Lake Powell and Lake Mead dropped to record-low levels in 2022, prompting federal officials to call for the biggest cuts to water use in the basin’s history.

Deane left Vidler in the early 2000s and co-founded the hedge fund Water Asset Management in 2005. Despite widespread media coverage of their activities, WAM executives rarely speak to the press. Headwaters invited WAM’s principal owners to comment for this article, but those requests were declined or went unanswered. An investor brochure published with the Securities and Exchange Commission says WAM caters to “high-net-worth individuals and institutional investors” willing to spend at least $1 million, and WAM’s website has limited information about the hedge fund’s activities.

Marc Robert, chief operation officer at WAM, outlined the fund’s investment model in a 2020 webinar, where he said WAM had already invested over $300 million in Western agriculture. Given water availability issues in the West, he said, WAM believes it’s necessary to “compel” landowners to operate more efficiently. In a slide titled “value creation,” Robert showed WAM’s efforts to buy and consolidate farmland, rent that land back to local operators, and work toward a long-term goal of leasing water to municipalities, industry, environmental users or others.

One concern is that, due to the shortage on the Colorado River, investors may be looking to profit from demand management programs that pay farmers not to irrigate during a drought, says author and water policy expert Eric Kuhn. “The fear today is … somebody

is going to be out there in the market,” he says, “looking for existing agricultural rights that consume water and saying, ‘I’m going to invest in those because somebody is going to pay me a lot of money not to farm in the future.’” This is a different profit model from the water

speculation that was prohibited under the Vidler Decision, and it is difficult to regulate because it involves buying water rights that are

already associated with agricultural land.

WAM’s investments in Colorado appear to have slowed in recent years, but its purchase of $100 million worth of farmland in Arizona in

2024 prompted criticism from Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes, who told the Parker Pioneer it could be the largest single water deal in

Arizona history.

Even though water is growing increasingly scarce, Wall Street still only plays a minor role in Colorado’s vast and complicated water

rights system. Joe Frank, general manager of the Lower South Platte Water Conservancy District in rural northeastern Colorado, says

investment water speculation — where water rights are purchased with the primary intent of profiting from a future sale or lease, rather

than a need to use that water — has not yet become a big issue in his district. Frank says traditional buy and dry remains a more pressing concern for farmers as cities grow and droughts deepen.

“You have a limited, finite supply of water and you have an increasing demand for water, primarily driven by the growth of the

Front Range,” Frank says. “There’s only so many places to go after that water, one of them being senior irrigation rights. That really

drives up the price and probably lends itself to the ability for a hedge fund to come in and speculate because they know the water is going

to continue to go up in value.” Balancing supply and demand and reducing municipal pursuit of senior irrigation water, Frank says,

should be a primary focus when combating both water speculation and buy and dry.

In some cases, additional water storage projects, cooperative agreements, and other solutions can help bolster supply. The Lower South Platte Water Conservancy District entered into a $1.2 billion deal with the Parker Water and Sanitation District and the City of Castle Rock in Douglas County over the past few years — the same region that Renewable Water Resources targeted in its scheme to export water from the San Luis Valley. The plan, known as the Platte Valley Water Partnership, will pay for the construction of new reservoirs and pipelines to allow for more spring runoff water in the South Platte River to be captured and shared by farmers on the northeastern plains and municipalities south of Denver. Frank says this plan is a win-win and is preferable to buy and dry, new legislation, or the valley export scheme.

Identifying and Regulating Water Speculation

Donovan, the rancher and former Colorado legislator, doesn’t see why hedge funds should play any role in making water use more efficient. In 2021, Donovan helped pass a bill that created a working group to study ways to strengthen anti-speculation water law in the state. The group — which consisted of stakeholders from a wide range of backgrounds, including the agricultural, environmental and legal communities — produced a 66-page report. It outlined the history of anti-speculation efforts in Colorado and attempted to define investment water speculation, but the group failed to reach consensus on any firm recommendations. “Some voices were louder than others,” she says, “and it left the legislature with few ideas to pursue.”

The working group did explore 19 “anti-speculation concepts,” listing the pros and cons for each. A low-hanging fruit explored by the

group, Donovan says, would be to make water rights more transparent so that the public can see who is buying and selling water.

Colorado Sen. Dylan Roberts (D-Eagle) has proposed draft bills in recent legislative sessions that would have treated water rights transfers like real estate, making transactions searchable in a publicly accessible database. “Transparency is where a lot of this could start

or should start if we’re going to add anything to our anti-speculation laws,” Roberts says, “making sure that people in Colorado understand who’s selling, who’s buying, and maybe put some light on what the prices are. I think that price gouging is more possible without transparency because people are coming up with sale prices completely on their own without doing comparison to other rights, which is the opposite of real estate.”

Multiple anti-speculation and transparency bills drafted by Donovan and Roberts died in the state senate. Related efforts on the federal level, including bills introduced by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), also went nowhere. Rep. Ruben Gallego (D-Ariz.) sponsored a 2023 bill that would have tasked the Federal Trade Commission to “create regulations prohibiting the sale or

lease of water rights at an excessive price in drought-stricken areas.” The effort, Gallego says, would ensure “shadowy Wall Street firms”

can’t “price gouge our farmers and communities in desperate need of water.” The bill never saw a vote.

Frank, the water conservancy district manager, served on the anti-speculation working group formed by the Colorado legislature, and he says sweeping proposals to change state water law give him pause. “We get scared a lot of times when we talk about changes to state law because we come from a rural, agrarian area where the prior appropriation system is bedrock to us,” he says. Frank added that he supports voluntary temporary leasing options for farmers and incentive programs for municipal water conservation over broad regulations and mandates.

Roberts and Donovan understand that perspective, but both said new legislation is needed to protect farmers and municipal users. Roberts believes his water rights transparency bill failed to gain bipartisan support in 2024 because it was misunderstood. In 2025, he plans to make transparency a formal topic of the Water Resources and Agriculture Review Committee, which he chairs, so experts can testify to lawmakers. “When you want to try to do something in water policy, it usually takes a couple years,” Roberts says. “You’ve got to have a lot of meetings, and you’ve got to make sure everybody gets their questions answered.”

The efforts could go much further, Donovan says. Other proposals include outlawing investment groups from holding water rights altogether or heavily taxing certain water rights transfers.

“The water world at large only responds when there’s a crisis,” she says, “not when we can see a crisis coming.”

Zak Podmore is an award-winning author and journalist who writes about water and conservation in the West. He is the author of two books: “Confluence: Navigating the Personal and Political on Rivers of the New West” (2019) and “Life After Dead Pool: Lake Powell’s Last Days and the Rebirth of the Colorado River” (2024).

Print

Print