In April 2024, the City of Aurora dropped $76.8 million on real estate in Otero County that included about 7,500 acre-feet of water rights per year, about $10,240 per acre-foot.

In northeastern Colorado, the price per acre-foot was even higher: In a February 2024 auction, the sellers of 90 shares of Colorado-Big Thompson (C-BT) Project water snagged about $52,000 per acre-foot per year. One acre-foot roughly equals the annual water use of two to four households.

For Chris Goemans, the high prices suggest something strange happening in the market. As a professor of agricultural and resource economics at Colorado State University, Goemans compares the productive value of water in an agricultural operation with what the resource is worth to a city. He says water prices are higher than what normal supply-and-demand. economics can explain.

He sees several reasons for the disparity. One is the limited amount of available water rights, a pool growing even smaller as municipalities buy rights to meet the needs of growing populations amid the unpredictable nature of climate change. This makes senior water rights — the ones allocated water first during times of scarcity — more reliable and, therefore, more valuable.

Another possible factor, Goemans says, is the presence of speculation in the market.

“One thing we worry about with speculation is that small groups of private entities could go in and purchase up lots of farms, lots of water rights, and they could kind of gain power in the water rights market,” Goemans says.

In other words, a single player would have the power to decide the cost of water rights. Municipalities in particular could find themselves forking over more and more money to support the water needs of their residents, Goemans says.

At the same time, economists have proposed — and in some cases installed — regulated water markets that encourage more trading and invite speculators to participate. Could the same thing happen in Colorado?

The System Governing Water Markets

In 1876, the state constitution put the doctrine of prior appropriation into law. It established that water in Colorado is public property, but that people can appropriate rights to use it. The doctrine also says that these rights can be transferred among water users in a variety of ways, including via sale, inheritance and more.

Another portion of the doctrine of prior appropriation creates rules around how the owner of a water right must use the resource. Water must be put to a beneficial use approved by a Colorado court. In Colorado’s early years, that beneficial use was often agricultural or industrial, but as the state approaches its 150th birthday, the beneficial uses have evolved. This essentially prohibits water speculation because a water right holder must use their water instead of sitting on it to resell for profit.

As more and more of Colorado’s water was appropriated, senior water rights became more valuable — creating a market for them. In the most basic version of the water market, the owner of a water right can sell it to any buyer for as much as that buyer is willing to pay. Owners can change how the water is used, as long as that change doesn’t impact other water rights and is approved by Colorado’s water courts.

The Gray Area of Speculation

Despite Colorado’s strict anti-speculation laws, the water market has evolved to allow certain behaviors that some observers say seem speculative.

Water courts sometimes grant conditional water rights, allowing someone to hold a water right without immediately putting it to beneficial use as long as they have a demonstrated plan to eventually use the water.

Zachary Gray, a shareholder with Frascona Joiner Goodman & Greenstein who practices law in Colorado, points out that “the very nature of conditional water rights are speculative,” though he says there are valid reasons to have them.

One of those reasons is exemplified by the C-BT Project, which moves water from the headwaters of the Colorado River to the South Platte River Basin for use in northeastern Colorado. The C-BT developer, Northern Water, secured conditional water rights so it could build the project without fearing water would be unavailable once the project was constructed, says Jeff Stahla, a Northern Water spokesperson.

At times, conditional water rights have been abused. Trout Unlimited argued in a 2009 Colorado Supreme Court case against a conditional water rights claim made by the Pagosa Area Water & Sanitation District. The utility claimed the ability to use far more water from Dry Gulch Reservoir than Trout Unlimited believed its residents would need in the future.

The Supreme Court ruled in Trout Unlimited’s favor, affirming that a municipality’s predicted growth must be substantiated in order to secure conditional water rights.

Companies purchasing farms and the water rights attached to them also spark speculation fears. For example, a Littleton based real estate firm, C&A Investors, has been purchasing land in Colorado’s Arkansas River Valley since the 1990s, according to Bill Grasmick, a C&A investor and farm manager overseeing some of the company’s properties in Otero County.

C&A’s 2024 deal with Aurora Water led to accusations of “buy and dry” behavior, with some arguing C&A had only purchased the farms to sell the water rights for profit.

But Grasmick, whose family has long farmed in the valley, says C&A helps the area’s economy. On the farms it purchased, C&A installed pivot irrigation systems, and ceased irrigating the corners of fields. That decision allowed for the sale and transfer of some of what was conserved.

Even though the firm has sold water rights, Grasmick says it’s not C&A’s main business — farming is. The company operates a greenhouse in Bent County and is also partnering with a dairy company to bring an operation to the area.

C&A hopes the shape of its deal with Aurora shows its commitment to keeping agriculture viable in Otero County. Aurora owns the water rights, but can lease that water back to C&A seven of the next 10 years.

“We think that’s a much more viable plan to work in a partnership with these people, like these municipalities and so forth, when they need the water, rather than to have them have to come in, buy it and dry it up and move the water out of the valley,” Grasmick says.

Everything C&A has done is legal under the rules of the market set forth by the prior appropriation doctrine, even if it raises eyebrows, says Goemans.

Alex Funk, director of water resources and senior counsel at the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, was part of Colorado’s Anti-Speculation Law Work Group. The group was formed by the legislature in 2020 to examine ways to strengthen anti-speculation laws.

The work group’s final report, in 2021, did not ultimately recommend new policy because it couldn’t find a good way to decipher the intent of buyers. “You go down so many rabbit holes trying to … basically looking into the mind of someone in terms of what they plan to do with the water,” Funk says.

City Impacts

Colorado’s water market is private, so the price tag on many transactions is unknown.

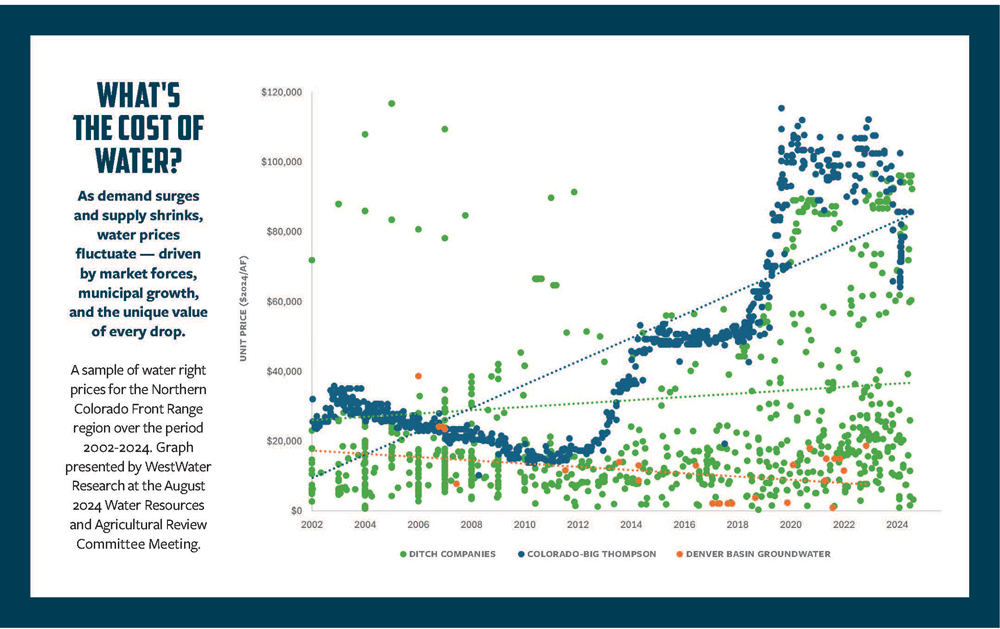

But the price of C-BT Project water provides an example of how much the right to use water has increased over the years. Price per unit huddled well under $3,000 for decades.

Then, until the mid-2010s, share prices fluctuated between $7,000 and $15,000, according to Northern Water.

Between 2013 and 2024, a single C-BT unit spiked from $15,065 to $67,000 — an increase of almost 345% — before settling in the $60,000 range.

Chart by Westwater Research

Population growth along the Interstate-25 corridor is one of the main factors driving the cost of water up. Alexandra Davis, assistant general manager of water supply and demand with Aurora Water, says that municipalities, including Aurora, rarely sell water rights once they’ve purchased them because cities are usually preparing for more people to arrive and for dry years.

That behavior makes water rights scarcer, increasing their price. The team at Aurora Water has seen private investors enter Colorado’s water market, including C&A, the company that sold the municipality land and water rights for $76.8 million. When Aurora has worked with those investors, water prices have tended to be a little higher than when the city works directly with farmers, says Davis, though she declined to say by how much.

Those higher prices increase the cost of development in growing cities like Aurora, said Shonnie Cline, a spokesperson with Aurora Water.

Other Markets

Colorado’s anti-speculation laws are considered among the toughest in the West, which, Goemans says, can slow down the rate of water rights transactions. Implementing the priority system in a water rights transaction isn’t something that a layperson can tackle on their own, he says.

“You have to hire engineers, attorneys, etc. to make sure, under our implementation of prior appropriation, that no other parties are injured by that transaction,” Goemans says.

While some may be squeamish about buying and selling a life-giving resource, a busy water market can have advantages.

Markets are an efficient tool that move resources from one place to another, says Billy Ferguson, an environmental economist and PhD student at Stanford University. They come with other advantages too. In his book “Liquid Asset,” Stanford Law professor Barton Thompson says that markets help ensure that water is put to its highest economic use. They can minimize economic losses during drought, he says — allowing junior water users to buy or lease water from senior users. Thompson argues that markets also encourage conservation (if an irrigator knows they can lease the water that they save, they are more likely to conserve).

Simplifying the rules around water rights could make buying and selling, or leasing, easier, and limit transaction costs, Ferguson says. He proposes a model where water rights would become more homogenous, indicating just source and quantity. In his model, users could sell or lease any unconsumed portion of their water right, encouraging conservation and trading.

If Ferguson’s proposal was pursued, modeling water consumption would likely result in the barriers to entry that exist in the current system, Goemans says. Creating a market that operates outside of prior appropriation, even if it does speed up water sales, would remove the positives of the current system, Goemans says.

“[Prior appropriation] really provides security for existing water rights holders in terms of the water supply they can expect under different types of climate conditions,” Goemans says.

Plus, Goemans says, market efficiency is not the only factor to consider in economics. Equity and fairness are important, too. “[Water] is a resource that many people think, from a fairness or equity standpoint, that everyone should have access to,” he says. “As economists, we can comment on the efficiency of certain outcomes, and we can comment on who is impacted, who is made better or worse off by different policies or allocation institutions … But then society has to figure out what is fair and what is not fair.”

Angela Ufheil is a freelance journalist and senior projects editor at the Denver Business Journal.

Print

Print