Keeping Colorado’s acres in ag means facing a multitude of challenges head-on

The landscape of Colorado agriculture is challenging, both metaphorically and literally. First, there’s climate change and variability. Take the 2013 flooding in northeastern Colorado and the 20-plus years of drought across the Colorado River Basin. Or the major wildfires that have ripped through the lands ranchers rely on for grazing their livestock, and the resulting continual sedimentation in rivers and ditches that producers use for crop irrigation. Then there are ongoing supply chain issues connected to the pandemic and the Ukrainian crisis, which have wrenched costs higher on everything from gas to fertilizer to tractors, and forced producers to make difficult decisions about whether they can afford to feed their cattle or if they need to fallow their fields. But the challenges with agriculture reach beyond production itself. Take rural healthcare, a top concern and contributor to the success of rural communities and producers. Keeping agriculture—a $47 billion business in Colorado and one of the state’s top industries—sustainable means facing all of those challenges, and others, head-on.

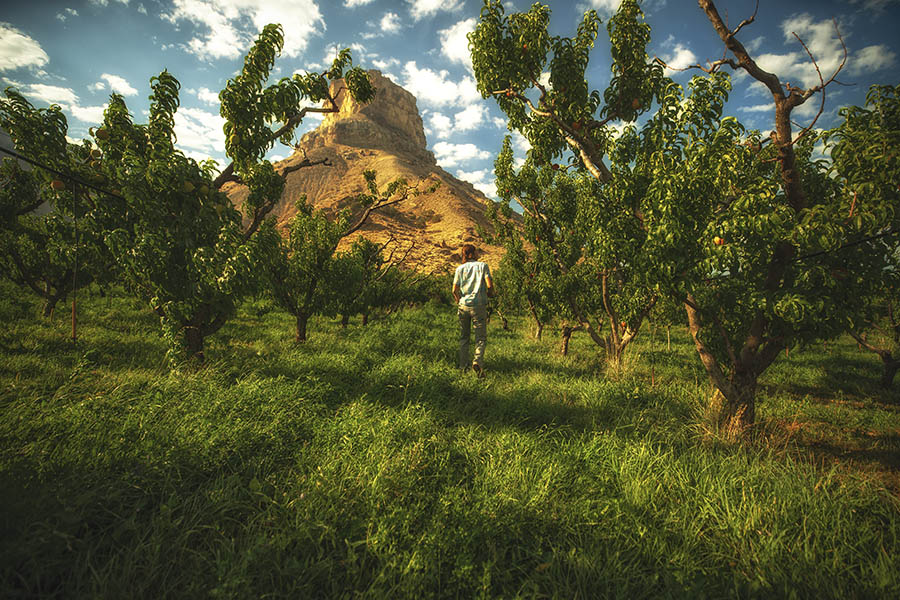

Kate Greenberg, Colorado’s Commissioner of Agriculture, spends about half of her time in the field, sitting around supper tables on peach farms and hay operations and cattle ranches, hearing from folks in community halls, and listening to concerns directly from producers as they work their land. Greenberg says that Colorado’s nearly 40,000 farms and ranches are preparing for and adapting to the onslaught of challenges, even though working in food and fiber is not easy during the best of times.

“Agriculture is sensitive to shifts in climate and economy, but it is also remarkably resilient,” Greenberg says. “That’s because people work their tails off.”

On a wheatfield in Akron, Colo., Kate Greenberg, Colorado’s Commissioner of Agriculture, meets with Colorado state Rep. Rod Pelton, Colorado Water Conservation Board board member Robert Sakata, and a local producer to see the effects and declines in yield that the wheat stem sawfly, a grassfeeding insect, can cause in wheat production.

Courtesy of the Colorado Department of Agriculture

While agriculture is not alone in experiencing these issues, Greenberg notes that producers feel the major impacts of crises like droughts first.

Dallas May has spent his entire life ranching and farming in southeastern Colorado, where his family had been leasing land since 1980, which they were finally able to purchase in 2012.

“We make big mortgage payments, and we don’t have room to stub our toes—everything has to work,” May says.

May had hoped that with Colorado snowpack upwards of the 90th percentile in the Arkansas River Basin this past winter, their water supply for the summer might be close to normal. But snowpack began to drop exponentially, and May says that his soil’s moisture profile has dried so much that even near-average moisture won’t make much difference.

Water is the most vital part of many producers’ businesses, which has forced them to figure out how to do business with fewer resources, says Greg Peterson, executive director of the Colorado Ag Water Alliance.

For example, many ranchers grow their own hay to feed the cattle they raise for profit. If there’s less water, they’re unable to grow as much hay, and if there’s less hay, that might mean significantly reducing a herd of cattle. Preliminary findings from a statewide 2020 drought survey conducted by Colorado State University (CSU) and the Colorado Ag Council found that about half of Colorado livestock producers reported that they reduced their herd size that year.

The economic impact of drought is significant. The CSU survey found that 45% of respondents received some type of financial relief due to 2020 drought conditions.

Farmers and ranchers don’t set the price of their own goods and are often trapped by rising and falling prices on both ends of the supply chain.

“Last year, the price of beef was up but the price of cattle was down. [Ranchers] were almost losing money,” Peterson explains. “Where so many businesses have the ability to just charge more, these people can’t.”

This is, in part, the result of lack of competition in the meatpacking industry. The four largest beef-packing firms control 85% of the U.S. beef market. These meatpackers buy from ranchers and sell to grocers, giving them price-setting power. According to a January briefing from the White House, ranchers today are making 39 cents for every dollar a consumer spends on beef, that’s down 35% from where it was 50 years ago, when ranchers made 60 cents per dollar.

All of this means more farms and ranches will be up for sale. The 2015 Colorado Water Plan estimates that, at worst, Colorado will lose 20% of its irrigated acreage in the next 30 years. The 2019 Technical Update to the Colorado Water Plan projects a 5% loss of agricultural lands statewide due to urbanization and the loss of some 33,000 to 76,000 acres or more in the Arkansas and South Platte river basins due to water rights purchases that have already occurred or are soon likely to occur, removing the water from the land to support growing cities and other uses. It also projects that 6% to 7% of irrigated acres supplied by groundwater will be lost due to aquifer sustainability issues.

Greg Peterson grows niche crops at his patchwork of small farms in the Denver metro area but also works with agricultural leaders statewide as director of the Colorado Ag Water Alliance, which aims to preserve agriculture through the wise use of Colorado’s water resources.

Matthew Staver

“That’s a lot of farms and ranches we’re going to lose, and we’re only going to need more food in the future,” Peterson says.

While Colorado’s population is growing and will need more food to sustain it—the U.S. Census Bureau reported that Colorado’s population grew at nearly twice the rate of the rest of the country between 2010 and 2020—food grown within Colorado isn’t always sold or consumed in the state or even the country. There are many reasons for this: Consumers demand an array of product choices, which large grocery retailers provide through their global supply chains. Supermarkets remain the dominant locale for food shopping, although the number of farm stands and direct sales from producers to consumers are increasing. The Colorado Blueprint of Agriculture and Food, a report produced in 2017 by researchers with CSU’s College of Agricultural Sciences, found that a lot of product both leaves and enters the state.

“It is not clear from the available data what share of the value of food and agricultural products sold at retail within Colorado actually came from Colorado agriculture,” the report’s authors write, attributing this to lack of data and the challenges of measuring such a complex value chain. But all of those products contribute to the state’s economy. Fresh beef is Colorado’s second largest export overall, behind only aircraft engines and parts, according to data from the World Trade Center Denver.

“Colorado’s economy is in rural Colorado, which produces products critical to both Colorado and the world,” says May. “Water has to stay in rural Colorado for everybody’s benefit, because once it’s gone, we may not be able to recover.”

Rural economies, populations and services play a role in agricultural sustainability as well. In rural areas, healthcare is often not physically or financially accessible—13 out of 64 counties in Colorado have no hospital and emergency medical services take an average of 34 minutes to respond in rural Colorado, according to the Colorado Farm Bureau’s 2020 Future of Agriculture in Colorado Task Force (FACT) report. This matters when farm and ranch production is hard, sometimes dangerous work and the population is aging—31% of farm and ranch operators are 65 or older, the report says. Critical services, such as healthcare, will separate some rural communities from others, the FACT report says. “Some will thrive and some will fail.” This has ramifications. If communities fail to attract new residents, the business environment that supports agricultural production could fail, causing operations themselves to fail.

Peterson says that awareness surrounding agriculture and its benefits is critical. “Agriculture is not optional,” Peterson says.

But these challenges aren’t all bad news, Peterson adds, pointing to his time in the Republican and Rio Grande river basins, which are two of the most water-short places in Colorado. When he sits in on meetings there with farmers and ranchers, Peterson sees something he hasn’t seen anywhere else.

“They’re talking about using less groundwater, voting to tax themselves now so they can maintain their communities in the future. No one is having that conversation in an urban setting—saying we should all make less money or use less of this resource so we can continue our way of life longer. It’s really interesting and heartening to watch,” Peterson says.

Alejandra Wilcox is a journalist based in northern Colorado. Her work has been broadcast on KGNU and has appeared in the HuffPost, among other outlets.

Print

Print