Even as aquifers dwindle, another question looms: What’s in the water we’re still drinking?

Like much of the Eastern Plains, no river systems run through the Upper Black Squirrel Creek Designated Ground Water Basin (UBS) in El Paso County. It is nearly 100% reliant on groundwater. So when the county’s population grew by almost 58% between 1990 and 2010, UBS district managers started to pay attention.

“As the growth started coming, we started to really be concerned about what that was doing to the water quality in the aquifer,” says UBS president Dave Doran.

UBS invested in a long-term water quality study with the El Paso County Commissioners and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). It became one of the most comprehensive aquifer characterization efforts in Colorado — and it’s still collecting data 15 years later. It uncovered issues in several parts of the basin, such as high concentrations of nitrates and the presence of pharmaceutical compounds. Today the insights are used to inform local municipalities and new construction.

But the study also pointed to a larger truth: maintaining groundwater quality is uniquely complex, and little is known about the impacts of urbanization and a changing climate across the state.

Shifting Geochemistry

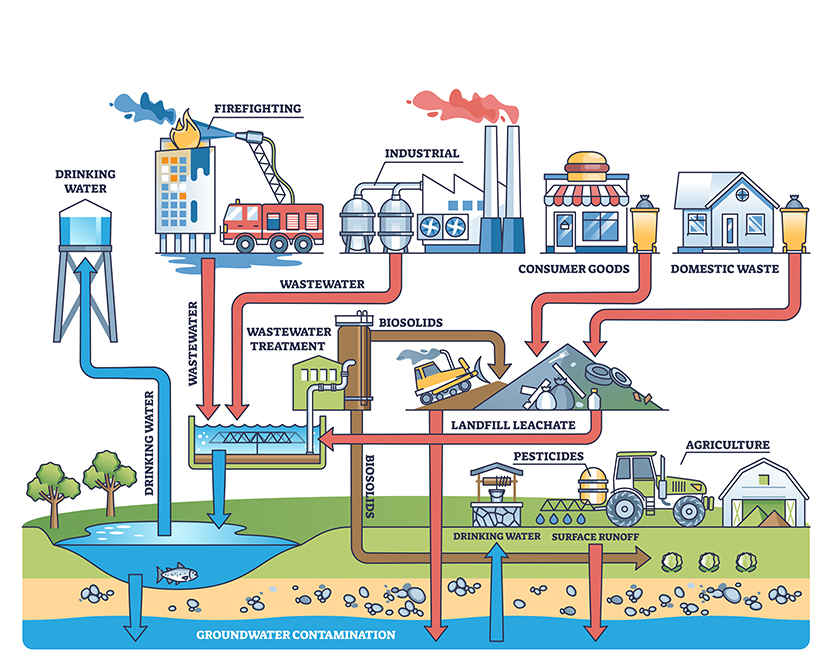

Common human-caused groundwater contaminants include nitrates from fertilizers, metals from abandoned and active mine waste, pharmaceutical compounds, personal-care products, and PFAS, according to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE). But groundwater quality is often impacted by naturally occurring compounds like arsenic, iron, manganese, selenium and radionuclides, too.

As water is pumped out of aquifers, different minerals and compounds are extracted, accumulate on land, and are fed back to aquifers. For example, certain rocks like shale have higher levels of salt ions that, over time, get weathered out into groundwater and contribute to increasing levels of salinity in places like the South Platte River Valley.

Colorado is also becoming warmer, drier and more populated, decreasing its aquifer levels. The geochemistry of the water shifts as it sinks farther from the ground’s surface, explains Katherine James, associate professor at Colorado School of Public Health. More aerobic conditions are created, and these conditions can cause naturally occurring metals, such as uranium, to dissolve into the water.

Groundwater recharge can impact aquifer water quality, too, even if the water has met regulatory standards. Mike Wireman, a retired hydrogeologist and consultant to UBS, explains that more research is needed.

“If you have groundwater in the aquifer of chemistry A, now you put water from the treatment plant of chemistry B into the aquifer with chemistry A, you end up with chemistry C. That fact is not adequately considered in state discharge regulations,” says Wireman. “It’s a problem.”

A Community Approach

Nationally, groundwater has been less studied than surface water, says Karen Schlatter, director at the Colorado Water Center.

“It’s invisible to us … we can’t see the immediate impact of our uses on it,” says Schlatter. “So there’s just been less monitoring, less regulation on this, unfortunately.”

For James, “it’s a nearly impossible ask” for regulations to keep up with new and emerging contaminants, which scientists are still actively studying and understanding.

“When most people were using plastic grocery bags … we never would have thought that microplastics were going to be a problem in water systems, and they are,” says James. “And we still don’t know a whole lot about it.”

Proper statistical analyses on water quality require large datasets, explains Zachary Kisfalusi, USGS Hydrologist working with UBS. More data is needed to provide a baseline across the state: “Even at the 50 wells we’ve sampled, some of these have only had two, three, or four data points. It’s hard to really say what is truly happening when you have such little data.”

Experts agree that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution, and heavy stakeholder engagement is necessary to tackle groundwater quality issues. UBS and other highly engaged communities serve as models for effective grassroots efforts to protect water resources.

“[Water] needs to be evaluated and considered in a way that respects the fact that the quality and the quantity [are] not guaranteed,” says James.

Emily Payne is a freelance writer who focuses on agriculture, food, health and climate.

Print

Print