In Texas, no water project can get a permit if it isn’t in the state water plan. In California, where an expressed goal of the state plan is to guide investments in water innovation and infrastructure, the plan essentially sets up for justifying—or not—ballot initiatives. Arizona’s plan, referred to as its strategic vision, is promoted as a comprehensive supply and demand analysis and framework to guide water planning efforts as far as 100 years out. New Mexico uses components of its water plan—statements of water need from its 16 regional plans—to inform litigation and negotiations with Texas over the Rio Grande Compact.

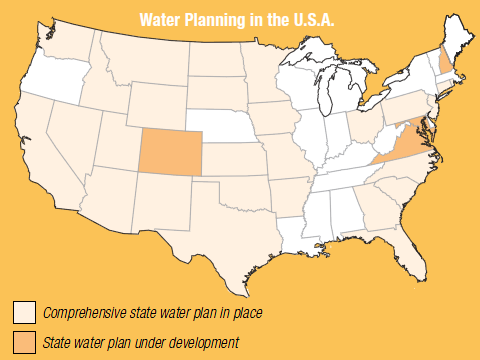

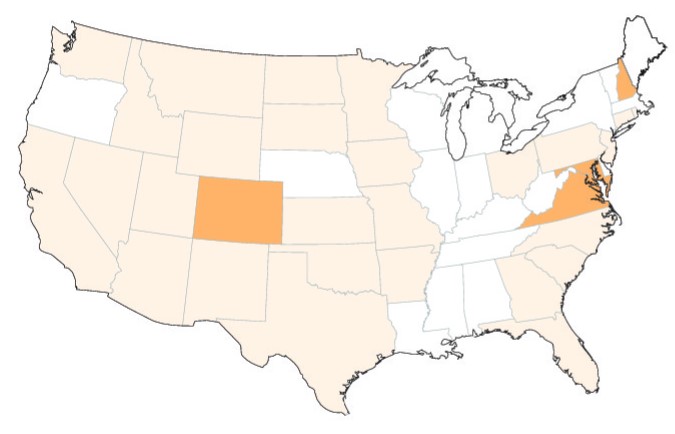

With the development of Colorado’s Water Plan, Colorado becomes one of the last western states to have a state plan for water, but it isn’t a replica of what anyone else has done. “Two years ago, Colorado Water Congress had a number of people in to represent what other state’s plans look like,” recalls John Stulp, special water policy advisor to Gov. John Hickenlooper. “The person from Texas told us, ‘Whatever you do, don’t copy ours. Make sure it’s a Colorado water plan. It needs to be done by Coloradans for your Colorado needs.’”

With the development of Colorado’s Water Plan, Colorado becomes one of the last western states to have a state plan for water, but it isn’t a replica of what anyone else has done. “Two years ago, Colorado Water Congress had a number of people in to represent what other state’s plans look like,” recalls John Stulp, special water policy advisor to Gov. John Hickenlooper. “The person from Texas told us, ‘Whatever you do, don’t copy ours. Make sure it’s a Colorado water plan. It needs to be done by Coloradans for your Colorado needs.’”

The structures of American states’ water planning run the gamut from more top-down approaches, such as those in California and the Dakotas, to grassroots, locally driven processes that blow even Colorado out of the water—but don’t necessarily make them more effective—like that of Washington, where 34 watershed planning units contribute to the plan, compared with Colorado’s nine basin roundtables. The plans vary accordingly with each state’s water supply picture, past experience, and legal structure.

In Colorado, where water rights are treated as private property rights, the grassroots process of state water planning that has been conducted through partnership with the basin roundtables is inherently needed. For other states, a more top-down approach works. Either way, there’s a balance to be struck between too much command and control and too much parochialism, where individuals are building fences around their resources.

Georgia, an example of eastern water planning, was experiencing water shortage and set out to create an implementable set of projects. Oklahoma, for its plan, set out to build technical tools that individual water providers could use to be successful in addressing their local water needs. Kansas does a little of both. It would seem there’s no wrong way to do water planning, as long as it’s clear what the plan’s objectives are. Experts say the plans that achieve the greatest success are those that can stay the course through political change, where their objectives stay true and outlive the administrations that go before them.

That doesn’t mean state water plans don’t need the occasional shoe shining. Utah, now working on a second revision to its plan, is adding sections looking at funding needs for replacement of water infrastructure, addressing canal safety issues, and incorporating climate change’s forecasted impacts, says Todd Adams, deputy director of Utah’s Division of Water Resources. And New Mexico is working on an update to better incorporate its regional plans—which were all developed before the first state plan was legislatively mandated in 2003—by updating them for consistency and uniformity, says Angela Bordegaray, state and regional water planner for the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission.

With the development of Colorado’s Water Plan, Colorado becomes one of the last western states to have a state plan for water, but it isn’t a replica of what anyone else has done.

State water planning in Texas has undergone many successive iterations since the first plan was put in place there in 1961. Texans in 2013 passed a ballot measure that re-appropriated approximately $2 billion from a state “rainy day fund” to a fund for implementing priority water projects articulated in the state water plan. “The projects also got some special treatment on interest rates and some grants for planning, but they had to comply with or be consistent with their regional plans as well as their state plan,” says Stulp, who suggests this may be a direction Colorado could head in future iterations of its plan, where projects having both regional support and consistent with the state plan could move along more quickly and receive help with at least a portion of the necessary financing.

Addressing a funding gap for water is certainly one aim of Colorado’s Water Plan, which could help the state better focus its limited resources. Colorado’s plan should also serve as a roadmap for balancing diverse values and interests across the state, says April Montgomery, chair of the Colorado Water Conservation Board and programs director at the Telluride Foundation. Not only do the basin roundtables now have their own regional plans for moving forward, but, she says, “all the water-related state agencies also have a guide. And certainly for the CWCB, as the policy arm of the state, this really provides a work plan for us moving forward. If you look at all the different action steps, this could keep us busy for a long time.”

Print

Print