To the casual observer, the Colorado River in Colorado looks like a natural river for the most part, tumbling noisily down mountain slopes and through canyons, or meandering quietly in open park-like floodplains.

Looking more closely, however, one begins to see that it is a very hard-working river. It may be as much a waterworks as a natural river today—a waterworks whose many tasks include continuing to look and function as much like a natural river as possible while carrying out a growing list of other responsibilities.

Some perceive this negatively as a crime against nature; others view it positively as a great human achievement in making much from a little. Strong arguments are made both ways today. Probably no other river in America so reflects the stresses inherent in the contradictory demands placed on finite resources.

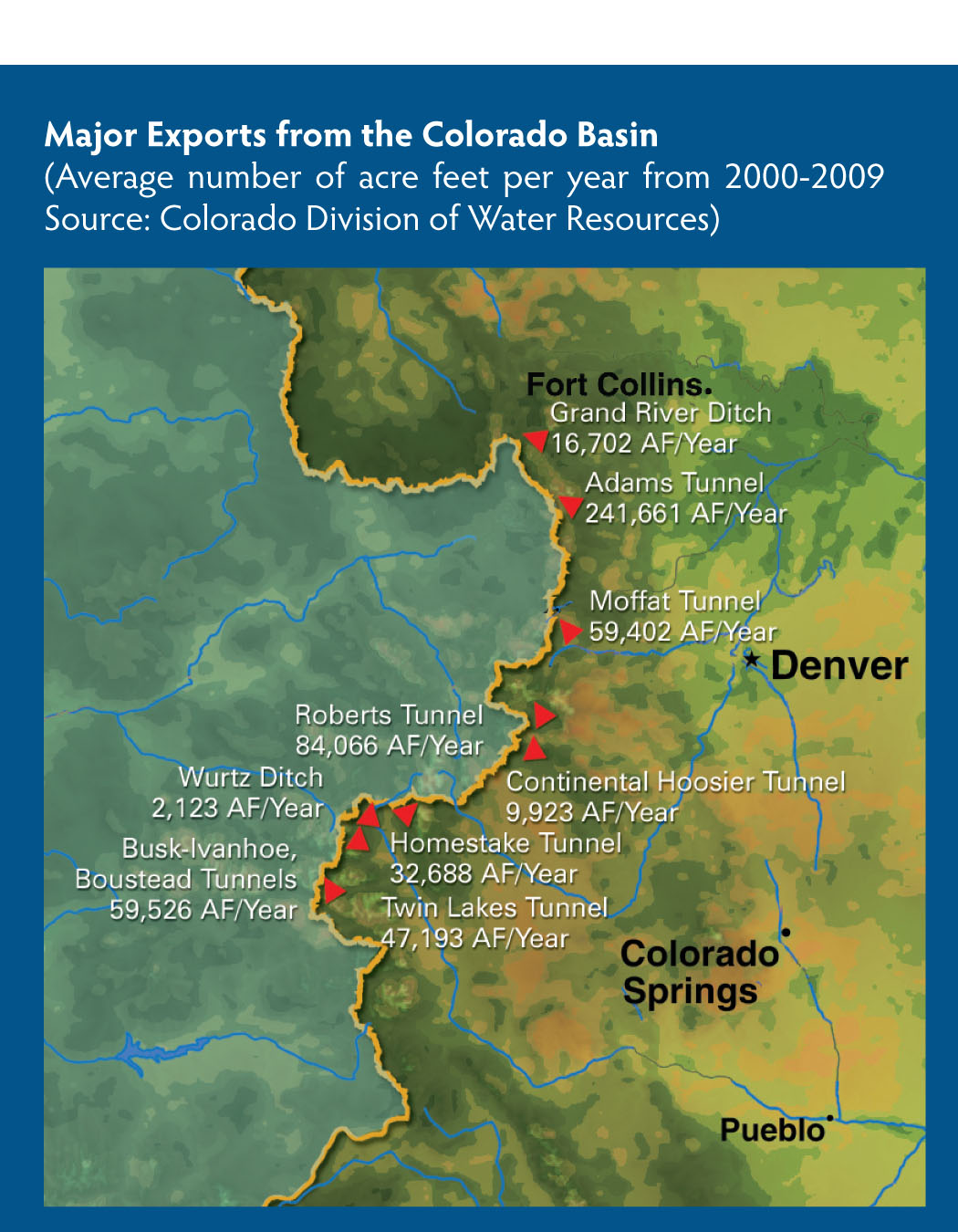

The Colorado mainstem itself and four of its larger headwaters tributaries—the Fraser, Williams Fork, Blue and Eagle rivers—have carved an eastward bulge in the Continental Divide that makes them accessible to the state’s drier and more populous eastern side, so even the highest waters are put to work, carried from collection canals to tunnels and out of the basin to satisfy needs on Colorado’s East Slope.

A little lower down in the headwaters tributaries, the mountain streams open into floodplains where the waterworks are more subtle. Modest irrigation systems spread water over hay fields, much of which makes its way back to the river as return flows. Similarly, headwaters towns like Breckenridge, Fraser, Granby or Kremmling take water from the river or its water table at one end of town and put 50 to 90 percent of it—treated, but not pristine—back in the river at the other end.

Some of the headwaters tributaries are interrupted by dams, creating reservoirs either to collect water for tunnels to the East Slope—in Shadow Mountain and Granby on the Colorado, Dillon on the Blue, and Ruedi on the Fryingpan—or to store it for late-summer irrigation on the West Slope—in Green Mountain on the Blue, Wolford Mountain on Muddy Creek, and Williams Fork Reservoir on the Williams Fork. These reservoirs also provide boating and fishing opportunities that have become substantial parts of the river basin’s economy.

From Kremmling to Glenwood Springs, the Colorado mainstem flows through mountains so rugged that most settlement has occurred south in the Eagle River Valley. There, a mixed heritage of mining and agricultural communities—Minturn, Eagle, Gypsum—have witnessed the more recent development of recreational meccas like Vail and Beaver Creek-Avon.

The Eagle joins the mainstem just above the spectacular Glenwood Canyon, where the river turns the turbines of the old, but very important, Shoshone hydropower plant. With a senior, 1902 priority for 1,250 cubic feet per second (cfs), Shoshone ensures that a substantial flow remains in the river from its headwaters tributaries.

Below Glenwood Springs and the mainstem’s confluence with its second-largest tributary, the Roaring Fork, “the middle river” meanders between Grand Mesa on the south and the Roan Plateau on the north, rich in rock-bound oil and gas. It works its way past more agricultural fields and towns—Silt, Rifle, Parachute—and more recently, a lot of gas wells, until it drops down the DeBeque Canyon to the Grand Valley Project Diversion Dam. There, the beginning of a complex of major irrigation works moves up to 2,260 cfs of water in irrigation season—in average or low years, at least as much as the river would naturally be carrying—out of the river and onto the high desert of the Grand Valley, in canals big enough to make one think of the term “hydraulic civilization.” From Palisade and Clifton past Grand Junction to Fruita, the basin’s largest and most productive agricultural area features fruit, vegetables and vineyards as well as hay fields and horse pastures.

After its “Grand Junction” with its largest tributary, the Gunnison River, the Colorado mainstem meanders west through cottonwoods along Interstate 70 before dropping into the canyons of the Colorado Plateau in Utah. It emerges hundreds of miles later in a huge “delta” for the serious desert hydraulic civilization bounded by Phoenix to the east and Los Angeles to the west, connected to the river’s flow only through hundreds of miles of pipelines and canals.

For all of the 20th century, Colorado inhabitants along the river’s mainstem have felt pressure from both directions, upstream and down. Some 30 million people depend to some extent on water from the larger Colorado River Basin, nearly a quarter of which originates in the mountains above the tributary valleys just described. More than four million of those people live across the Continental Divide in Colorado and get roughly half a million acre feet of the river’s purest water, about the same as what is used within the mainstem basin itself. Downstream, “the Law of the River”—a series of interstate compacts and federal laws—commits Colorado to annually let millions of acre feet of Colorado River water leave the state for the desert empire below. An average of 2.6 million acre feet of the mainstem basin’s water crosses the state line each year.

From the perspective of Coloradans who live along the mainstem and its tributaries, those 2.6 million acre feet are easier to let go of than the half-million that leave the headwaters to cross the Continental Divide. They, and their friends and customers from other regions, get to fish in, float on and otherwise “use” that water as it passes by, while the transmountain diversions are forever removed from the river.

Grand Lake and the largest diversion project in the upper basin of the Colorado. Water that would normally drain into the Colorado is canalled east from WIllow Creek Reservoir (bottom) into Lake Granby, then pumped uphill into Shadow Mountain Reservoir, which connects to Grand Lake and the Adams Tunnel beneath the Rockies. It took 19 years and $168 million to build 12 of these Colorado Big Thompson Project (CBT) reservoirs. Originally designed to rescue Colorado farms devastated by the 1930s Dust Bowl, the CBT reservoirs now largely supply the surging eastern-slope population north of Boulder – 800,000 people across 35 cities and towns outside the Colorado River Basin. Photo By: Peter McBride

The Colorado-Big Thompson Project, which moves on average 230,000 acre feet annually through the Alva B. Adams tunnel under Rocky Mountain National Park, is the biggest transmountain diversion from the headwaters, accounting for nearly half of the basin’s water taken east. Most of this used to be supplemental, late-season agricultural water for South Platte Basin farmers, but today two-thirds of it is owned by municipalities in the northern part of Colorado’s Front Range. Denver and its South Platte suburbs take another 150,000 acre feet per year through the Moffat and Roberts tunnels, and another 130,000 acre feet go to the south metro area and Arkansas Basin through the Twin Lakes, Boustead, Homestake and other smaller tunnels.

Would the Front Range urban corridor that largely drives Colorado’s economy and boasts many of its universities and cultural centers be possible without West Slope water? Possibly, but only through the unsustainable and undesirable practices of pumping depletable aquifers to exhaustion and large-scale conversion of agricultural water to municipal and industrial use.

Since the 1930s push for a Colorado-Big Thompson Project, the West Slope has fought vigorously for “compensatory storage” from East Slope diverters to make up for the loss of water and its impact on future opportunities. The West Slope had some heroes in that struggle: Clifford Stone, who helped create and first directed the Colorado Water Conservation Board from 1937 until he died in harness in 1952, and Frank Delaney, who developed the Colorado River Water Conservation District, or “the River District.” Stone and Delaney believed that the East and West slopes could help each other develop Colorado’s share of the larger Colorado River allotment, but encountered short-sighted opponents on both sides of the Divide. They were aided by two multi-term West Slope congressmen—Edward Taylor (1908-1941) and Wayne Aspinall (1948-1972)—who unabashedly used seniority autocratically to serve their underdog district.

The East Slope has also had heroes in the ongoing effort to bring cooperation to a contentious issue: Charles Hansen and J. M. Dille of the South Platte Basin, who worked patiently to develop a Colorado-Big Thompson Project fair to both slopes; Harold Roberts, Denver Water Board attorney, who ended a decade-long standoff over the Blue River through the radical approach of talking to the other side; and Chips Barry, manager of Denver Water, who acknowledged in the 1990s that water allocation involved the negotiation of moral as well as legal issues.

The West Slope was successful in getting two compensatory mainstem reservoirs on Bureau of Reclamation projects: Green Mountain Reservoir on the Blue River as part of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project and Ruedi Reservoir on the Fryingpan River as part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project. These reservoirs were designed not only to protect senior water users downstream, but also to provide water for the West Slope’s prospective needs.

Higher on the Blue River, however, for half a century the Denver Water Board vigorously fought the idea that the state’s “great and growing cities” owed any compensation for water appropriated legally from the West Slope. But a number of setbacks in court plus, perhaps, the realization that Colorado’s growing metropolis needed the West Slope at least as much as the West Slope needed the city, brought a change in philosophy around 1990. Denver Water, the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, the burgeoning cities north of Denver in the South Platte Basin, and the River District began to collaborate rather than contend and jointly financed and built Wolford Mountain Reservoir above Kremmling, a key element in what is now a complex but integrated trans-Divide water supply system that attempts to nurture the growing cities on the east side while sustaining a living river and healthy economies on the west side.

This complex but integrated water supply system may be improved further by a newly proposed Colorado River Cooperative Agreement, five years in the negotiating, that gets one last bit of water for the Front Range cities in exchange for quite a bit of money to reconstruct vulnerable stretches of the mainstem and a commitment to “operate” the headwaters tributaries to maximize benefits to both sides of the Divide.

But a big question along the mainstem today is whether it really is possible to operate this heavily managed waterworks enough like a river to maintain the economy through which it runs. Upstream from Glenwood Springs, year-round tourism, recreation and resorts are the major economy along both the river and its tributaries—an economy most needful of waterways that resemble a natural river.

This recreational emphasis is not a new development. The oldest continuing water right in the Colorado mainstem basin is for the mineral baths that drew early tourists to Hot Sulphur Springs. Later, in negotiating the Colorado-Big Thompson Project, headwaters communities wanted protection for fishing streams, already a major part of the local economy.

Today, concern about the life of the river has grown as that economy has grown—even as the flows have grown smaller. And measurable economic impacts from visitors say little about the extent to which such “amenities” are part of the reason why 300,000 people put up with hard winters and marginal service economies to live in the basin.

“To develop Colorado’s unused Colorado River water, we either need to devise projects that better manage existing supplies and use more wet year water or go farther west.” – Eric Kuhn

Coloradans on both slopes also recognize that there are ecological reasons transcending the economic for keeping a river alive and reasonably healthy, not least being the abundant wildlife that depend on it. In addition, diverse problems with water quality—mine metals high up, dissolved alkaloids below Glenwood Springs—nag most stretches of the river in a water-short situation where “dilution as a solution” is not always an option. The extent to which storage for heavy usage has changed the river’s flow also contributes to the endangered status of four species of warm-water fish near Grand Junction.

Energy production below Glenwood Springs—gas, shale oil, coal for electricity—is another “challenge and opportunity” looming over the basin. Heavy energy development could add another 120,000 acre feet to in-basin consumptive water use—currently around 550,000 acre feet along the Colorado River mainstem, mostly agricultural. Those agricultural users already believe they are 100,000 acre feet short on what they truly need to irrigate the land that has been cultivated. At the same time, additional water demand within the basin will come from a growing regional population, predicted to more than double by 2050. The combination of urbanization and conversion of agricultural water to municipal uses could result in as much as 30 percent of the basin’s 268,000 current irrigated acres being taken out of production in a basin proud of this industry.

Faced with these pressures, the Colorado Basin Roundtable, a legally constituted “grassroots voice” for the river and its people, economy and ecology, lays its position on the line in a draft vision statement: “Any additional transmountain diversions [from the Colorado River mainstem and its tributaries] must be considered as the last resort to support Front Range growth.” The proposed Colorado River Cooperative Agreement seems to affirm that—after just a little more mainstem diversion.

Eight years ago, in Congressional testimony, Colorado River District general manager Eric Kuhn said, “To develop Colorado’s unused Colorado River water, we either need to devise projects that better manage existing supplies and use more wet year water or go farther west.” He cited the example of a “Big Straw” study to pump water from the Colorado River below Grand Junction all the way back to the Continental Divide: “[That] may seem like an extreme example. However, the reality is that in all of 2001, all of 2002, and most of 2003, one would have had to go all the way to Grand Junction to find any water that was available for use for a new appropriator.”

The mainstem and tributaries of the Colorado River in Colorado are on the front lines of America’s 21st-century challenge: balancing the desire to eat the cake with the desire to have it too. There is hope in the high level of democratic collaboration that is occurring across the state. But it remains a lot to ask of an increasingly overworked river. In an interconnected Colorado, where residents benefit from a strong agricultural economy, abundant recreational opportunities and the cultural offerings of the larger cities, all dependent on Colorado River water, a current awareness campaign by the River District and Northwest Colorado Council of Governments serves as a poignant reminder of the resource’s ultimate limitations: “It’s the same water.”

Print

Print