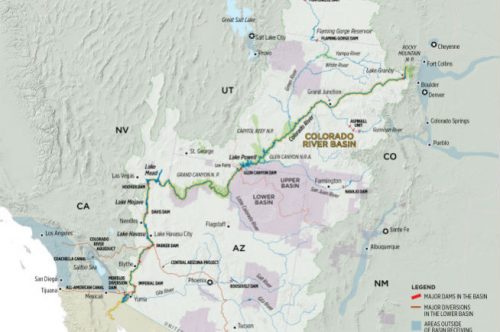

As the crisis on the Colorado River continues, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the four Upper Basin states—Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming—have drawn up a proposed framework called the Upper Basin Drought Response Operations Plan. The framework would be used by water managers to create plans each year, as necessary, to maintain Lake Powell water levels.

The effort to keep Lake Powell healthy is critical to ensuring hydropower production from its turbines is maintained and to protect the Upper Basin states from violating their legal obligation to send Colorado River water to Arizona, California and Nevada, the Lower Basin states.

Whether the new plan will be activated this year is uncertain. During a webinar about the working draft on Jan. 28, Rod Smith, an attorney with the U.S. Department of Interior, described this year’s early winter weather as a yo-yo. “December was excellent,” he said, “but January was kind of blah.”

Public comments on the proposed plan are being accepted through Thursday, Feb. 17.

Lake Powell’s water levels were successfully stabilized last year after a series of major emergency water releases from reservoirs in Utah and Colorado. Lower Basin states also cut water use.

Modeling last year had found a nearly 90% probability that Powell levels in 2022 would fall below the elevation of 3,525, triggering more emergency releases. But as of Feb. 3, water levels in Powell were almost 6 feet above that elevation.

Much can change between now and April, when Reclamation and the states hope to complete the framework.

Last year’s disastrous runoff — the snowpack was roughly 85% of average but the runoff was 32% of average — surprised everyone, and ultimately forced the emergency releases from Blue Mesa and Flaming Gorge, two of three federal dams operated by the agency upstream of Powell. Reclamation also operates Navajo, the reservoir located primarily in New Mexico, whose waters can also be used to boost levels in Powell, subject to other limitations.

The proposed framework identifies how much water from the three reservoirs is available for release to prop up levels in Powell, but only after operations at Powell itself have been managed to best maintain levels of 3,525 feet or above. To slow the decline, Reclamation is holding back 350,000 acre-feet of water in Powell that it would normally release during January-April.

The agency plans this year to release 7.48 million acre-feet from Powell to flow down the Grand Canyon to Lake Mead.

Smith emphasized that the releases from Blue Mesa and other Upper Basin reservoirs will be subordinate to the many preexisting governance mechanisms on the Colorado River, including treaties, compacts, statutes, reserve rights, contracts, records of decision and so forth. “All that stays,” said Smith.

This can get complicated. For example, some water from Taylor Park Reservoir, near Crested Butte, can be stored in Blue Mesa but is really meant for farmers and other users in the Montrose-Olathe area. That water is off-limits in this planning.

Navajo Reservoir releases can get even more complicated. Water was initially identified last summer for release from the reservoir to help replenish Powell, but then delayed. Reasons were identified, including temperatures of the San Juan River downstream in Utah. But feathers were ruffled, as was revealed during the Colorado River Water Users Association meeting, held in Las Vegas in December. Tribes were consulted only belatedly.

Now, the draft framework language specifies the need for consultation with tribes. Water in Navajo Reservoir is owned by both the Jicarilla Apache and Navajo. To be considered are diversions to farmers but also to Gallup. “Getting this right, particularly in the operational phase, will be critical,” said Smith.

How might this affect ditch systems in Colorado? “There will be timing issues of when the extra water comes down, but in terms of whether there are any direct impacts to a ditch authority operating under its own decree, there should not be,” said Michelle Garrison, senior water resource specialist with the Colorado Water Conservation Board, during the webinar. “We don’t expect any disruption to other water users because of this.”

Reclamation has received at least one comment that it should give up hopes of bolstering levels in Powell. Save the Colorado’s Gary Wockner called for Powell to be drained and Glen Canyon Dam destroyed.

Others were inclined toward more charitable appraisals of the drought framework.

“You can help make the best of a bad situation by having any drought operation releases benefit other things on the river, including benefits to threatened and endangered fish species while potentially producing more hydropower revenue [used in part to support endangered fish recovery programs],” said Bart Miller, water program manager for Western Resource Advocates.

But Miller and others also note that Reclamation’s draft framework represents a short-term solution to a festering long-term problem.

The word drought is found everywhere in the planning documents. Colorado State University climate scientist Brad Udall insists that another word, aridification, better describes the hydrology that has left the Colorado River with nearly 20% less water in the 21st century as compared to the 20th century. Trying to reconcile 21st century hydrology with 20th century infrastructure and governance is like walking on a rail that gets ever more narrow.

“I think it’s totally appropriate to use this tool but not as a substitute for dealing with the overall imbalance between supply and demand,” says Anne Castle, a senior fellow at the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy and the Environment at the University of Colorado Law School.

Long-time Colorado journalist Allen Best publishes Big Pivots, an e-magazine that covers energy and other transitions in Colorado. He can be reached at allen@bigpivots.com and allen.best@comcast.net.

Fresh Water News is an independent, nonpartisan news initiative of Water Education Colorado. WEco is funded by multiple donors. Our editorial policy and donor list can be viewed at wateredco.org.

Print

Print