For northern Colorado, September 2013 was hell. At the time, the National Weather Service called the flooding “biblical.” For those impacted, it might as well have been. Farmers watched herds of mice scurry across wet fields to reach higher ground and avoid inundation—the first plague. People, too, struggled to survive and protect family, animals and property. Those assisting with emergency response and rescue efforts lived on adrenaline, Snickers bars and without sleep for days. It felt like the rains would never stop. Ten lives were lost. Hell.

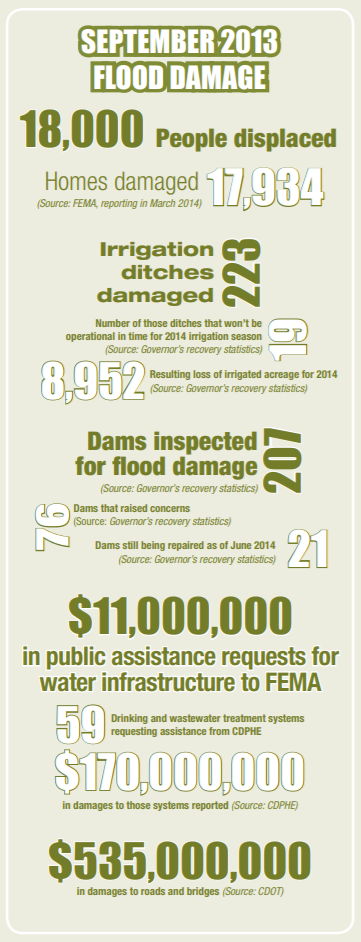

Although total economic losses and flood-related damages won’t be known with certainty for years, state officials are estimating the tally at around $3.4 billion. In the end, that number will include damage to agricultural land and production, tourism losses, as well as impacts to homes, businesses, roads and more.

Repairs and rebuilding continue, but less than a year out it’s too soon to say what Colorado will remember and learn from the event and what will become lore.

The storm began forming along Colorado’s Western Slope on September 7. The previous week was record-breakingly hot and dry, says Nolan Doesken, Colorado’s State Climatologist. Tropical moisture heading north from the Pacific coast of Mexico had swept across the desert Southwest, targeting western

Colorado. Kevin Houck, chief of watershed and flood protection for the Colorado Water Conservation Board, recalls emailing Doesken after checking the precipitation forecast, hopeful for a few inches of rain—drought relief. At the time, Doesken told him not to get too excited, these storms rarely pan out.

Soldiers, airmen and members of civilian emergency response agencies unload sandbags to stymie floodwaters in Arvada on Sept. 15, 2013. Photo by Air Force Staff Sgt. Nicole Manzanares, Colorado National Guard

By September 9, that moisture moved to the Front Range. As rain showers began to fall, another mass of soggy, humid air was sweeping up from the Texas Gulf coast pumping water in like a pipeline, says Mike Chard, director of the Boulder Office of Emergency Management. The dew point was 67 degrees, and “everything was just right for this to turn into a bad day,” Chard recalls.

Even as that Gulf air was driven up against the foothills to meet the Pacific-sourced moisture, a stalled low-pressure front was circulating, making it difficult for forecasters to predict the enormity of the storm and where the rain would fall. In the end, that circulating front kept the moisture pointed at Colorado’s East Slope for the better part of a week.

Army Staff Sgt. Jose Pantoja (left) hoists evacuee Mike Daniels into a Blackhawk medevac helicopter during rescue operations in Boulder on Sept. 16, 2013. Photo by Sgt. Jonathan C. Thibault, U.S. Army

By the afternoon of Wednesday the 11th, heavy rains started. “This was the beginning of the main show,” Doesken says. Emergency managers activated and all eyes were on the weather. As rain began falling, people first reacted with excitement. College students were tubing in Boulder Creek and playing in the water, but by 8:30 that night the mood had shifted, says Amy Danzl with the Boulder Office of Emergency Management. Danzl was monitoring social media and felt the darkness of the event when tweets and Facebook messages became fearful. “Just got home after driving through waters in Boulder that completely blew up over my windshield and thunder crashing,” Boulder resident Morgan Heim posted on Facebook around 10 p.m. “Now the flash flood sirens are going off all over the city, and it is not a test. Sounds like the end of the world, and I’m grateful to have gotten home.”

The rains continued all week, shifting intensity and focus from as far south as El Paso County in the Arkansas River Basin and casting a wide berth northward along the Front Range. Rains poured down heaviest from 5 p.m. on the 11th until 1 a.m. the morning of the 13th, creating flood surges targeting Larimer, Boulder and Jefferson counties. On the 12th, the heaviest rains focused on Aurora, northeast Denver and parts of Weld County, causing flooding in Sand Creek and a crisis for Denver’s Metro Wastewater plant. The 12th also saw, at Fort Carson south of Colorado Springs, more rain falling in a 24-hour period than ever before recorded by a Colorado rain gauge. Those southern rains were at their wildest slightly east, around Fountain Creek.

That same day, the rains shifted west, striking the upper watersheds of the Big Thompson River and St. Vrain Creek, even pouring west of Evergreen. This western hit set the stage for tumultuous flooding that developed that night on the Big Thompson. As floodwaters rose, in many cases there was no place for people to go, no roads on which to evacuate, and yet the rain was still falling. Emergency managers struggled to keep people safe, making plans so rescue helicopters could fly as soon as the storm lifted.

An aerial view shows flood damage in Colorado on Sept. 14, 2013. U.S. Army photo by Staff Sgt. Wallace Bonner

Misinformation was proliferating. In Lyons, someone made a loudspeaker announcement that Buttonrock Dam was failing—if Buttonrock failed, Lyons wouldn’t survive. Officials and emergency managers received numerous dam failure reports and with each report had to reconfirm the dam was safely intact. As water came pouring over dam spillways, as with Buttonrock, many citizens may not have realized the dams were functioning according to design in response to rising water levels.

Other faulty information spread through social media networks. Rogue personalities posted dangerously false information like directing people to evacuate in the wrong direction. For days public information officers answered phones, maintained a social media presence, and quelled the major sources of misinformation.

By Friday, September 13, the rains slowed enough for rescue helicopters to fly. At the same time, floodwaters were consolidating. Due to the storm’s large footprint, entire watersheds were flooding. Water pounded down creeks, channels and tributaries, and roaring streams converged to tear through canyons and pour from their mouths. Stream channels were reshaped and rerouted, with flood magnitudes varying by location. According to the Natural Resources Conservation Service, many high country creeks exceeded the 100-year flood level; some exceeded it by as much as five times.

Floodwaters submerge fields and a road on the outskirts of Longmont. Photo by Terry Plummer

By the time the rushing St. Vrain, Poudre and Big Thompson rivers hit the South Platte out in the plains, they formed a towering flood wave that surged around Greeley. Floodwaters, in an area that itself received only a few inches of rainfall during the storm, breached river banks and flowed more than a mile wide in places, causing severe flooding in Logan, Morgan, Sedgwick and Weld counties. Three rivers overtopped Interstate 25 and all major roads across the northern Front Range closed. On the 14th, local thunderstorms again hit west Aurora and Denver and again sent floodwaters rolling down Sand Creek to Metro Wastewater. Then came an all-day rain over the entire region on the 15th. Finally, on a soggy Monday, September 16, the rain subsided and full rescue efforts, assessments and repairs could begin.

After the flood, news media went wild—people wanted information. “I probably had more media touches in two weeks during the floods than I did in my almost 25-year career here,” says Steve Gunderson, director of the Water Quality Control Division at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE). Flooded oil and gas wells and tipped tanks leaking crude oil quickly became the focus of a concerned national audience. But with the release of water quality analyses, the story died quickly.

The Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission estimates losing 43,000 gallons of crude oil to surface water, a large number diminished by the comparative volume of wastewater that was rushing down the South Platte. CDPHE estimates releases of 20 million gallons of raw sewage and as much as 270 million gallons of partially treated sewage, Gunderson says. When water quality was tested after the floods, samples revealed highly elevated levels of E. Coli, stemming from wastewater, while volatile organic compounds related to oil and gas production were below human health standards. A month later, E. Coli levels had returned to normal.

In the course of the storm, rainfall totals were high, peaking at 18 inches around Boulder and 15 inches in Aurora, with pockets of concentrated rainfall reaching 14 to 16 inches in the mountains south of Estes Park, west of Lyons, and northwest of Loveland. Compare that to an average annual precipitation of 12 to 16 inches at

The South Platte River flooded U.S. Highway 34 east of Greeley. Photos by Mark Goldstein (3)

lower elevations and 16 to 23 inches along the Peak to Peak Highway, plus average September precipitation east of the Continental Divide of less than 2 inches. “The problem was, we got the better part of a year’s worth of precipitation in a week, with the bulk of that in a day and a half,” Doesken says.

There were other problematic factors that exacerbated the flooding and the damage. Settlement patterns in Front Range canyons have evolved and more people are living in these areas than ever before. Small access trails have become larger paved roads, roads that in some cases constitute half the floodplain’s width and restrict a river’s natural movement. Roads and bridges racked up an estimated $535 million in damages during the flood, but the pavement also helped channel water to rip directly down canyons.

A partially ruined cornfield is revealed as floodwaters recede

in Weld County.

The risk of living so closely to wild areas has also manifested in the many wildfires that have ravaged Colorado, burning all the more brightly due to years of suppression to protect homes. The burn scars from those wildfires in turn intensify the rush of water and debris into rivers during rain events.

Still, September’s flood could have been worse. Mitigation work completed after previous floods dampened the effects of this most recent deluge. In 1965 the South Platte River was hit with what was previously the most economically destructive flood in Colorado’s history, a $3 billion disaster. Many say it’s the most comparable to the September 2013 flood: a June storm that swept south of Denver with 10-plus inches of rain, which fell in just over three hours destroying roads, bridges, homes and other structures in the South Platte’s floodplain. This was the flood that led to construction of Chatfield Reservoir as a flood-control mechanism.

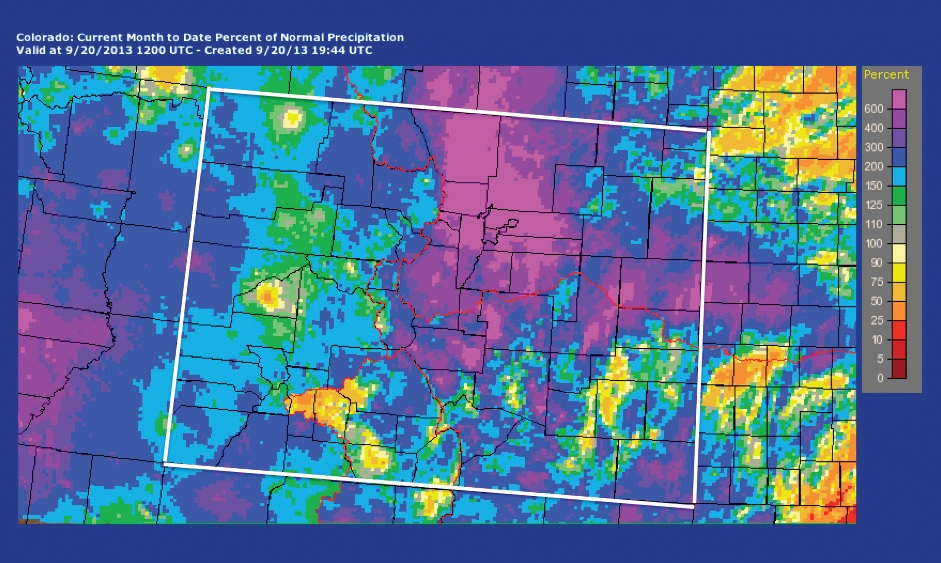

EXTREME RAIN EVENT—By Sept. 20, 2013, the month-to-date percent of average precipitation that had fallen where the storm was concentrated (east of the Continental Divide and along the northern Front Range) reached more than 600 percent of normal for September. Source: Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service

It also prompted creation of the Urban Drainage and Flood Control District, a regional organization that reaches seven counties around the metro area. Upon establishment by state legislation, the organization immediately took an inventory of drainages in its district, finding 74 percent undeveloped and amenable to flood prevention approaches.

It also prompted creation of the Urban Drainage and Flood Control District, a regional organization that reaches seven counties around the metro area. Upon establishment by state legislation, the organization immediately took an inventory of drainages in its district, finding 74 percent undeveloped and amenable to flood prevention approaches.

Five years later, the district established floodplain management programs to keep those floodplains undeveloped, offering financial incentives to encourage local governments to maintain healthy river channels, establish greenways and stabilize streambanks. They also worked with cities on smart development and master planning. Bill DeGroot, recently retired manager of the district’s floodplain management program, says that in his 40 years there, he never issued a floodplain development permit.

Such floodplain protection efforts paid off in September 2013. A project in Denver’s Stapleton neighborhood along Westerly Creek was built through Urban Drainage’s maintenance eligibility program, and although a pedestrian bridge over the creek was underwater during the September 2013 flood, there was no damage to surrounding property. The same was true in western Aurora, which received as much rainfall as Boulder but saw little severe damage. “A lot of the activities that the cities did in conjunction with the Urban Drainage and Flood Control District, it was almost like nothing happened there,” Houck says. “There were some roads that buckled, but really it was kind of a non-story in the Denver area.” Then again, these areas were further from the mountains and mouths of canyons, where flood energy was more concentrated.

Other floodplain work has been completed around the state with coordination of cities, parks and open space departments, and nonprofits. The 2013 flood put two City of Longmont flood mitigation projects to the test, both of which were completed within the past four years. Work along Left Hand Creek benefitted many homes previously located in the floodplain, and another project along a gulch successfully diverted floodwaters to large holding ponds. Denver’s Greenway Foundation, which also got its start in 1974, opened up the floodplains along the South Platte River and Cherry Creek, creating riparian buffers and recreation areas between the river and uphill development. Similarly, the Fountain Creek Watershed Flood Control and Greenway District has been working on restoration projects to improve flood control throughout Fountain Creek’s watershed since 2009. “You can go to cities around the state and see some places that are doing this,” Houck says. “I’m hoping that will limit the actual flooding events that we experience.”

The Big Thompson Flood of 1976 was the deadliest flash flood in Colorado. On the night of July 31, the mouth of the Big Thompson Canyon carried 32,000 cubic feet per second of water, and it came on fast. In the end, there were 144 victims. That deadly flood was high and quick compared to the September 2013 flooding where flows were more sustained and peaked around 15,500 cfs on the Big Thompson at the end of the canyon. As a result of the Big Thompson Flood, Colorado posted “climb to safety” signs in canyons and raised public awareness about the risk of flash flooding.

Flooded oil and gas operations spilled tens of thousands of gallons of crude oil in Weld County. Photo By: Mark Goldstein

“This [September 2013 flood] is the No. 1 flood in our history from a dollar-loss amount and it doesn’t even rank in the top six for deaths,” Chard says. Ten tragically died in September, but most are relieved that more lives weren’t lost. “We had every way and every reason to have 10 times more than those deaths, statewide,” Chard says. He attributes the reduction to early warning and other steps taken to mitigate risk. Still, emergency managers continue working to improve their systems so they’ll be better prepared to respond quickly when the next emergency strikes.

Although Colorado has grown more resilient and prepared with each disaster, it’s hard to say what the state will learn from September 2013. “Events kind of tend to fade into memory and people will always talk about it, but the event develops this mythical status as if, ‘Oh, it was the big one,’” says Houck. He cites the Big Thompson Flood as the last “big one,” yet here we are with another big one less than 40 years later.

Trailer homes were no match for the raging South St. Vrain Creek in Lyons. Photo by Bonnie-Sue Hitchcock

According to Doesken, floods happen in Colorado nearly every year, big floods happen about every three to five years, and really big floods happen roughly every decade. But people tend to think a disaster won’t hit them, and if it does, they expect there won’t be another, Houck says.

Society may monumentalize this flood, or forget the likelihood of recurrence, but emergency managers can’t afford to be negligent. Each disaster shapes the landscape and brings with it new risk in the future. While reviewing lessons learned with his team of responders, Chard told them to stay on their toes: “Folks, we’re facing flood season. I’ve got a [wildfire] burn scar—that risk still hasn’t changed—and we’ve got wildfire season right around the corner. I’m just getting your heads wrapped around the reality…you’d better have another one in you, because we’re going to be needing you.”

- The flood ripped apart thousands of private residences and left them filled with mud and debris. Photo by Tom Browning

- Many roadways were overwhelmed by surging rivers laden with debris. Photo by Bonnie-Sue Hitchcock

- An aerial view shows damage to a road in Colorado due to flooding on Sept. 16, 2013. U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Jonathan C. Thibault

Print

Print