When the final draft of Colorado’s Water Plan lands with a thump on the governor’s desk at the end of 2015—or, more likely, when it appears with a cheerful ping in his email inbox—it will be the product of what James Eklund, director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB), calls “the largest civic engagement project in Colorado.” That project, the statewide system of grassroots basin roundtables established by the 2005 Colorado Water for the 21st Century Act, has played a pivotal role in the creation of the water plan, but despite the hundreds of meetings held, thousands of hours worked, and tens of thousands of pages reviewed, the true test of the plan lies ahead.

That test is whether state officials, roundtable members, lawmakers and water providers can successfully implement the plan, and whether they can leverage its findings and recommendations to stave off a statewide water supply reckoning in the decades to come. The alternative outcome involves the plan—which is, after all, a non-enforceable advisory document—dying a quiet death on the shelf of a government office. Such a fate seems unlikely given the outpouring of time and public input that has gone into the effort so far, but implementing it successfully will still require action and cooperation from all corners of the water community. What’s more, it could require improvements to the laws and regulations, planning and permitting processes, and funding mechanisms that affect building new water projects and conserving, sharing and reusing Colorado’s water.

If it’s doable, do it. If not, legislate.

Once completed, the water plan will be nothing less than a massive, multi-decade to-do list for basin roundtables, interest groups, state agencies and water providers alike. From the moment the final plan is submitted in late 2015 until the next time it’s updated, these groups will be busy building and implementing the projects and programs that the plan identifies, hopefully in a fashion consistent with the “No and Low Regrets” actions recommended to shrink the future water gap by the Interbasin Compact Committee (IBCC).

Yet starting in early 2016, the Colorado state legislature will also weigh in on the future of the water plan. Chapter 10 of the plan, which is currently empty but serves as a placeholder to be developed in 2015, will be dedicated exclusively to legislative recommendations, providing lawmakers with a chance to make an informed difference by passing new water laws or funding new water projects.

Although legislation could be an important outcome of the water plan, lawmakers have already begun to shape the plan’s contents. Under Senate Bill 115, passed and signed by the governor in 2013, a group of lawmakers called the interim Water Resources Review Committee (WRRC) held public hearings on the plan during the initial drafting process and can continue to do so every time a new draft or significant amendment is released. During meetings the group held during the summer of 2014 in all eight of Colorado’s river basins and the Denver Metro area, more than 500 people attended and more than 160 submitted spoken or written comments on the water plan. The WRRC can also propose legislation based on the water plan-related input its members receive, and although the bills referred to the legislature for the 2015 session didn’t directly relate to the water plan, some cover similar ground. One bill, for instance, would promote rainwater harvesting projects that reduce demand on reservoirs, rivers and streams, while another would create a grant program for the management of invasive weeds like tamarisk that crowd riverbanks and consume large amounts of water.

Former state Rep. Randy Fischer, a Fort Collins Democrat who co-chaired the 2014 WRRC public hearings along with former Snowmass Village Democratic Sen. Gail Schwartz, says several dominant themes emerged in the public comments legislators heard on the water plan. “We heard that there are tradeoffs to everything, and even though there is universal agreement that agricultural ‘buy and dry’ shouldn’t be the default mechanism for meeting future water demands, it’s not enough to simply say, ‘We want to prevent buy and dry,’” Fischer says. After all, as Colorado’s population grows and water’s price rises along with demand, it will likely become more and more difficult for farmers and ranchers to resist selling their water. That makes it vital for Colorado’s Water Plan to identify and encourage buy and dry alternatives like rotational fallowing, interruptible supply agreements and other alternative transfer methods (ATMs), which are based on the notion that many cities and towns only need extra water in very dry years, and thus could stand to lease instead of own agricultural water rights.

“There was a great example given by a commenter in Steamboat, where he pointed out that the water it takes to grow 6,000 tons of hay could also supply around 5,000 households,” Fischer recalls. “The economic value of the output produced by 5,000 households is many times greater than the sale price of the hay. So how can the people raising hay possibly compete with those interested in their water supplies?” Fischer hopes the water plan will help show that they don’t have to by boosting state support for the most promising ATMs.

The draft plan sets a goal of freeing up 50,000 acre-feet of municipal water supply per year from such arrangements, whether it be through rotational fallowing, deficit irrigation or other measures that could provide water as needed or, in some cases, consistently every year to cities while farmers temporarily use a little less. The CWCB has been funding research into ATMs for years and has awarded about a dozen grants for ATM pilot projects, although none of those are fully developed yet. Some state legislators have also jumped in to encourage the use of ATMs in the past, but despite all this government goodwill, the tools haven’t been widely implemented in Colorado. That’s partly because it’s expensive to win approval for ATM projects from a water court judge, the State Engineer or the CWCB. Another contributing factor is that irrigators fear entering into an ATM agreement, having their historical water use scrutinized, and potentially being forced to forfeit some of their water under what is perceived by many in Colorado to be a “use it or lose it” water law.

Peter Nichols, a water attorney and partner at the Boulder firm Berg, Hill, Greenleaf and Ruscitti, believes there are several legal and administrative tweaks that legislators and state regulators could make to ease the financial burden of the ATM approval process. Nichols currently represents two Arkansas Valley agricultural water providers in their bid to lease water owned by irrigators on the Catlin Canal and relay it to municipalities near Rocky Ford in a rotational fallowing agreement. One major expense in planning such a project, he says, is hiring private engineers to determine whether it will harm other irrigators on the ditch. The state has a spreadsheet tool that can analyze this question relatively cheaply, and Nichols says mandating its use during the approval process could minimize expensive back-and-forth battles between water engineers and attorneys on each side.

In addition, Nichols says there’s a need for a more precise definition of what it means to harm a downstream water user through an ATM project, and the state legislature could pass a bill defining that in order to minimize frivolous claims of injury by irrigators on the same ditch as a proposed ATM project. “People right now are being hyper-protective of their rights,” Nichols says. “The current law seems to think that anything an engineer can model could constitute injury.”

Once completed, the water plan will be nothing less than a massive, multi-decade to-do list for basin roundtables, interest groups, state agencies and water providers alike.

Honoring Colorado’s commitment to local control

Even if the state is successful in closing the municipal water supply gap by 50,000 acre-feet through ATMs, there will be a long way to go. The least impactful solution, many argue, is to shrink the gap by improving demand management across the state. Maybe we just need to use less. It’s not that simple, however. One hurdle for the water plan when it comes to setting statewide goals for implementing solutions such as conservation is that Colorado’s water management system is largely predicated on the notion that local governments and special districts—rather than state bureaucrats—are better suited to address local challenges. In the coming years, a critical test of the water plan will be how well it navigates the balance between state and local control.

That tension is likely to surface most prominently in discussions of whether future development projects—like the homes and apartment buildings that’ll house Colorado’s millions of new arrivals by 2050—should be required to embrace specific water conservation and efficiency targets. Given the extent of Colorado’s expected growth, many water managers believe marrying land use and water planning will be essential to minimizing future water demand and the need for additional supply projects. But there’s some disagreement over whether these policies should be dictated locally or by the state, especially when decisions made in one region can have implications for another.

“What seems to be missing from the discussion is the fact that if one basin is short of water and goes looking for it in another basin, that constrains the ability of the affected basin to develop for its own future,” says Barbara Green, an attorney for the Water Quality and Quantity Committee of the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments, which advocates for the interests of Colorado’s headwaters communities. If future land use policies on the booming Front Range don’t encourage water conservation, Green says, it will affect not only the landscape—and waterscape—of the Front Range, but also the economies of places like Otero County or Grand County where Front Range interests might go in search of water to meet their demands.

The draft water plan doesn’t advocate mandatory statewide rules that would infringe upon local control, including the locally prized “1041 powers” enshrined in state law, but instead recommends things like expedited permitting or tax incentives for projects that incorporate water efficiency or density measures. In the same vein, another bill referred out of the state legislature’s Water Resources Review Committee for consideration during the 2015 legislative session would require the CWCB to offer free trainings to local planning and land use officials on water demand management and conservation. If those officials then proposed a water project and sought state funding to support it, state agencies could consider their water efficiency training in deciding whether to fund the project.

Local governments already have a wide array of powers they can use to affect the timing, location, density and type of growth in their communities. For Green, the pressing question is whether they’ll have the political courage to use it in the future.

Building and funding better projects

In piecing together Colorado’s future water puzzle, the construction of some new projects will be essential, whether they be for reusing water, improving irrigation diversion structures, laying pipes that enable water sharing, or building or enlarging reservoirs. Many water managers say improvements are needed to the project funding and permitting processes that will enable such projects to proceed in a timely manner. The draft water plan recommends several of these.

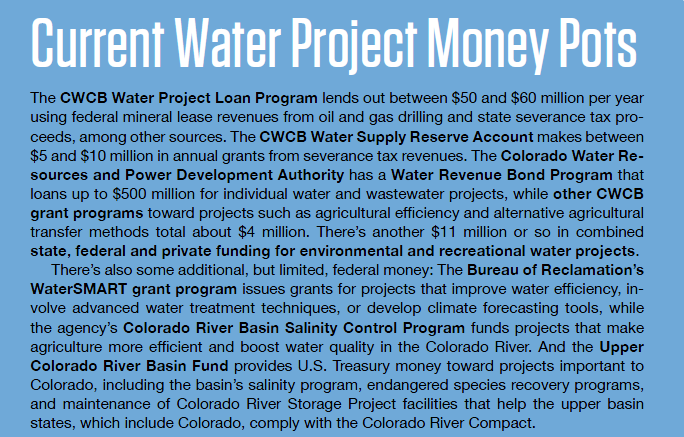

On the funding front, Colorado has several sources of state money for water infrastructure that, in total, provide up to $560 million in loans and between $9 and $14 million in grants each year. There’s another $11 million or so in combined state, federal and private funding for environmental and recreational water projects. There’s also some additional, limited federal money.

Yet the projected demand for public water project funding far exceeds the current supply. Along with the $17 to $19 billion in funding needed for municipal and industrial projects that water providers could build by 2050, another pot of money will be required for environmental projects like stream restoration, which can cost anywhere from about $150,000 per stream mile all the way up to $500,000. To better quantify the need for stream restoration, the water plan recommends creating up to 90 watershed-level master plans, and just assembling those could cost $18 million.

To help close the funding gap, the water plan offers several potential solutions. Existing caps on the Federal Mineral Lease and Severance Tax revenue that goes to fund water projects could be removed; the state itself could become a partner in some multi-purpose, multi-partner water projects; or water providers could enter into public/private partnerships to share the risk and reward of building new water projects with private companies. Another option is that the state or water providers could push for a voter-approved tax increase to fund water infrastructure. During the last major push for such funding, in 2003, Colorado voters flatly rejected a $2 billion water bond, even though it was put forth at a time when water needs would have been high on people’s minds following the 2002 drought. The water plan points out that any future request for a tax increase would require a more detailed explanation of the money’s intended uses, which wasn’t supplied at that time.

To help close the funding gap, the water plan offers several potential solutions.

Will we permit a better way to permit?

In addition to the issue of funding, many water managers say the time and expense now required to get state and federal permits—millions of dollars and more than 10 years, in some cases—makes it uncertain that planned projects will come online soon enough to meet projected water needs.

“Anyone that deals with the need to do projects will always complain about the regulatory requirements,” says Jim Broderick, chair of the Arkansas Basin Roundtable and executive director of the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District, who is currently shepherding the 130-mile-long Arkansas Valley Conduit from Pueblo to Lamar and a set of hydroelectric turbines planned for Pueblo Reservoir through the permitting process. “Sometimes that’s justified, sometimes it’s not justified. But people are certainly saying that the process should be quicker than what we’re seeing now.”

The list of permits required to move forward with a major water project is lengthy. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment issues discharge and water quality certifications under the federal Clean Water Act; Colorado Parks and Wildlife works with the CWCB to approve mitigation plans that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service then ensures comply with the federal Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act; the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Bureau of Reclamation, Forest Service or another federal agency takes the lead in issuing Clean Water Act Section 404 permits for fill and dredging in U.S. waters; and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reviews the environmental analyses mandated by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), a federal law requiring a project be completed in a manner consistent with the “least environmentally damaging practicable alternative.”

Given the complexity of the process, opportunities for delay or confusion abound. Karen Hamilton, chief of the Aquatic Resource Protection and Accountability Unit in the EPA’s Region 8 office in Denver, says her agency is working on a tool to help water managers navigate the process that may ultimately be incorporated into a permitting handbook the CWCB has identified as an action step in the draft of Colorado’s Water Plan. “We describe the process, where we’ve seen people get hung up, and what our recommendations are for making those bumps a little smaller, if not making them go away,” says Hamilton. Among those recommendations: Water providers should coordinate early with federal agencies to understand what is going to be required during the permitting process, and they should use NEPA guidelines during the design phase to come up with the “least environmentally damaging” project from the start. The true intent of NEPA, Hamilton points out, is to be a planning, not a permitting, process.

Complexity aside, another problem that utility managers often ascribe to the permitting process is a duplication of effort between state and federal agencies. “The biggest issue that we run into is that the federal and state processes are not well coordinated,” says Dave Little, director of planning for Denver Water. “You have a massive effort in scoping all the federal environmental documents, and the state gets involved later in the process and says, ‘Wait a minute, you forgot to study this!’”

Becky Mitchell, section chief of Water Supply Planning for the CWCB, acknowledges room for improvement in the way the state and federal permitting processes intersect. “Currently, the state’s input on these projects doesn’t come along until later in the process, so you’re not getting any positive statements from the state until you’ve gone basically halfway through the NEPA process,” she says. “The water plan will examine whether there’s some way that the state can say up front, ‘This is a really important project,’ which ideally would expedite the federal permitting process.” Winning state endorsement, Mitchell says, probably won’t require that a project endures a whole new level of review, merely that state agencies get involved earlier and consider additional criteria during their evaluations. She says modifying the process this way also probably won’t require legislative approval.

Some environmental groups have raised concerns about the idea of the state endorsing a specific water project, including the possibility that it could water down the federal environmental review process. “The idea of having these agencies work together to create a cohesive process makes sense,” says Ken Neubecker, the Colorado River Program director for the environmental group American Rivers, “as long as it doesn’t change the conclusions that they’re coming up with.”

In March 2014, a coalition of environmental groups including Western Resource Advocates, Conservation Colorado, Trout Unlimited, American Rivers and others submitted a letter with recommended criteria for state support, arguing that a project should only win state approval after its backer has achieved high levels of conservation in existing water uses, has plans to recycle all its legally reusable water, and has already explored other ways of firming, or boosting, the yield of existing projects, sharing infrastructure with other water providers, or sharing water with agricultural producers.

The draft plan in Section 9.4 contains the conceptual framework of a process for moving a project through state assessment earlier in the permitting phases and, if criteria were satisfied, issuing state support. While the coalition’s recommendations may have influenced the conceptual framework, the factors currently listed for consideration in the draft plan don’t go as far. For instance, rather than requiring a project proponent have plans to recycle all its legally reusable water or achieve high conservation levels, the draft framework states that the proponent must demonstrate sustainability by providing “a conservation plan or plans aimed at reducing demands.” Other factors the draft plan lays out for fulfillment prior to state involvement: that a project proponent commit to mitigating or avoiding impacts to water quality as well as the agricultural community and to engaging in local government consultation and a stakeholder and public input process.

Protecting rivers, for real

Recent polling data as well as comments submitted on the water plan to date reveal Coloradans’ strong commitment to protecting the state’s rivers. Colorado’s Water Plan, too, acknowledges the value of maintaining healthy rivers, but exactly how this is to be accomplished remains unclear. Even as the basin roundtables have identified projects or, in some cases, processes for moving water that help meet recreational and environmental needs by keeping water in streams, many conservation groups say details in the draft water plan for protecting streamflows remain vague, and they’re calling for more specificity as the draft is revised. They also point out that the lack of adequate science surrounding biological values, which aren’t as easily quantified as municipal water use (multiply the number of people by average per capita daily use and add a percentage loss factor), means environmental needs could easily be shortchanged by other pressing demands. Nowhere does this possibility raise more red flags than with the potential new diversion and transfer of water from one river basin to another.

Craig Mackey, pictured at Denver’s Confluence Park, works with Protect the Flows to ensure the Colorado River Basin can sustain symbiotic values that include business, recreation, the environment and quality of life. Photo By: Kevin Moloney

Trout Unlimited, a conservation group with more than 10,000 members across Colorado, in September 2014 submitted to the CWCB a statement containing five core values, requesting their incorporation into the plan. The values, endorsed by 635 individuals and entities representing tens of thousands of Coloradans, include promoting “cooperation, not conflict” and “innovative management” along with opposing “new, large-scale, river-damaging transbasin diversions of water from the Colorado River to the Front Range.” Richard Van Gytenbeek, Colorado River Basin outreach coordinator for Trout Unlimited, says that statement is not an outright rejection of a transmountain diversion, but an expectation that Colorado’s Water Plan should “provide mechanisms that will accurately demonstrate that any plans for a transbasin diversion will not compromise the health of West Slope rivers and streams and the communities that depend on them.” To accomplish this, says Van Gytenbeek, the plan should identify funding sources for stream environmental assessments that define flushing, optimal and base flow regimes, while focusing increased attention on in-basin solutions such as conservation and reuse. “Ultimately, each basin must find ways to exist and thrive within the limits of their own water supplies,” he says. “Limited natural resources can only be stretched to a limit before they are compromised and degraded.”

Beyond the transmountain diversion concern, many environmentalists support the water plan’s recommendation for more state funding for creative water-sharing techniques that benefit aquatic ecosystems, such as periodic “pulse flows” that mimic floods by overtopping riverbanks, clearing out sediment, and maintaining healthy riparian zones. Such flows could also be mandated as conditions of approval for future water projects, helping to blunt their environmental impacts.

“A lot of water providers are happy to work with environmentalists on minimum streamflows, but when you start talking about things like riparian overbanking flows, they look at you like you’re crazy,” says Neubecker. “I’d like to see the water plan recognize the importance of the flows that are needed to maintain a healthy ecosystem, not just the ‘Disneyland’ flows necessary for rafting and fishing.”

Teaching Coloradans how water really works

If local governments and utilities are going to win public support for new water projects, be they to meet environmental, agricultural, municipal or some combination of demands, they’ll have to ensure Coloradans are well educated about how the state’s water system works and what it takes to bring water to the kitchen faucet—or to keep it in the stream.

Research points to an urgent need for more water education. In a 2013 survey by the firm BBC Research and Consulting, more than two-thirds of Coloradans polled believed that Colorado does not have enough water for the next 40 years. As the draft water plan reports, the survey also found most people are unaware of the main uses of water in the state and are uncertain of how to best meet Colorado’s future water needs.

The draft water plan suggests numerous ways to boost water education in Colorado, including using the basin roundtables to keep public engagement high after the plan is released and establishing a new outreach, education and public engagement grant fund administered by the CWCB.

Among the state’s most urgent educational needs is making Front Range residents aware of their dependence, through transbasin diversions, on the Colorado River on the opposite side of the Continental Divide, says John Stulp, special water policy advisor to Gov. John Hickenlooper.

“We’re all tied together by the Colorado River Compact,” Stulp says. “And so that’s been part of the educational effort, to make people on the Front Range…realize that they’re tied into that compact every bit as much as people in the far reaches of the Western Slope are.”

Another pressing need is to bring new voices into the Colorado water discussion, including parties—like much of the state’s business community—that have been largely absent in the past. “Water is not an extremely sexy subject, so it’s hard, but hopefully there will be a lot of good press and analysis [now that] the water plan is on the governor’s desk that will help raise awareness,” says Mizraim Cordero, director of the Colorado Competitive Council (C3), which lobbies the Colorado legislature on behalf of Colorado businesses and chambers of commerce. “In the meantime, the role of business groups like ours is to push the information and push the subject to businesses that are just busy doing what they do every day, solving problems [unrelated to water].”

A final educational priority that should be considered is acquainting people with the true cost of water—which means accounting for everything from protecting source watersheds and waterways to building, operating and maintaining modern, efficient infrastructure such as water storage, pipelines, pumps and water treatment facilities. That’s according to Craig Mackey, co-director of Protect the Flows, a coalition of 1,100 businesses, from rafting companies to hotels, that depend on the flows of the Colorado River. The group advocates for water conservation as a first line of defense against pending water shortages and emphasizes the economic benefit of leaving water in the Colorado River. Building the water projects of the future, encouraging conservation and developing programs to share water between multiple users, Mackey says, will certainly require higher water rates.

According to the draft water plan, for example, water reuse will be an important way to stretch finite water resources across the state, and the Colorado, Arkansas and South Platte basins could be particularly reliant on reuse projects in the coming years. But some of the biggest barriers to reuse are the expenses associated with pumping water back upstream, treating it to meet water quality standards, and complying with regulations governing disposal of the brine waste produced as a byproduct of treatment. Some residents may be more willing to pick up the tab once they understand that reusing existing water supplies, where legally and technically feasible, can maximize use of the state’s waters while reducing the need to pursue other less favored options, such as transmountain diversions or permanent agricultural dry-up.

For such an essential and heavily monitored resource, water is now amazingly cheap. As the draft water plan notes, just 1 percent of the average Colorado household’s income presently goes toward paying the water bill. We’ll spend $1.00 or more for 12 ounces of water at the grocery store, while we turn on the tap and get 1,000 gallons treated and delivered to our home for $3.00.

“How do we prepare the business community and the citizenry for a world where water is going to cost more, and moving water is going to cost more?” Mackey asks. “I don’t expect the water plan to directly address water rates, but perhaps it can help people understand why water should be more expensive.”

Print

Print