Peter Binney remembers the precise moment when the bad news hit. It was the early summer of 2002, and Colorado was in the throes of the worst drought in more than a century. By fall, most Coloradans would feel the effects of the disaster: Crops would be scorched in fields from the South Platte Basin to the San Luis Valley, rafting and fishing guides on the Western Slope would lose income due to low flows, and water users in downtown Denver would see sharp rate hikes and usage restrictions.

In June, though, Binney, with only a few months under his belt as the new director of Aurora Water, was still wondering how much Rocky Mountain snowmelt Aurora could count on to fill its reservoirs that year. He was on his way to Pueblo for a meeting when Aurora’s water supply manager called him with the answer. “It was a lightning bolt,” remembers Binney, who left Aurora Water in 2008 and is now head of sustainable infrastructure at the engineering firm Merrick and Co., a consultant to The Nature Conservancy on water reuse issues, and a member of the Metro Basin Roundtable. “I knew the number was going to be low, but I had no idea it would be lower than theoretically possible.” Aurora, Binney’s water manager said, was likely to get just 8,000 acre-feet of water for reservoir storage in 2002, compared to 70,000 acre-feet in a typical year. The city would be forced to dramatically draw down its reservoirs to survive the summer, and if the drought didn’t lift in 2003, Aurora could run out of water entirely.

After the initial shock, Binney and his colleagues sprang into action. In the ensuing months they raised water rates, instituted outdoor watering restrictions, and lined up emergency water supplies. Mother nature granted a reprieve of her own on March 18, 2003, when she graced the Denver metro area with a whopping 30-plus inches of snow in a storm that put the region on the road to recovery. Still, the drought of 2002 had thoroughly shaken water managers by showing them—for the first time in recent memory—the true limits of their water supplies.

“We realized that Aurora’s water portfolio was very vulnerable to weather conditions, and it didn’t have the capacity to weather the storm—or the lack of a storm,” Binney says.

“The drought gave us an absolute display of what’s going to happen if Colorado’s water runs out. Call it the canary in the coal mine, if you will.” – Peter Binney

Gov. John Hickenlooper took office in 2011 and ordered the drafting of a state water plan in 2013. Photo By: Kevin Moloney

Battling shortage in a brave new world

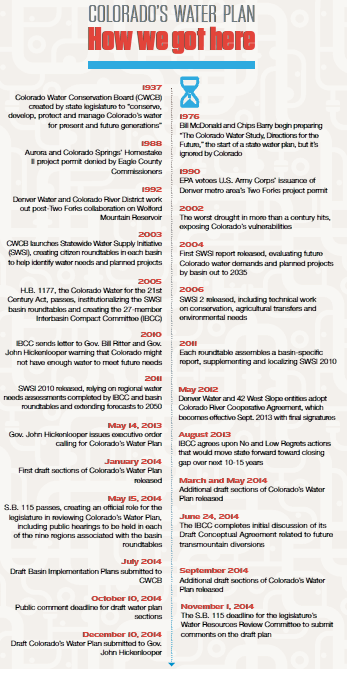

Water shortage is every utility manager’s nightmare, and it’s also a deep-seated fear for nature lovers, river rafters, farmers, business people, and anyone else whose lifestyle is floated by Colorado’s water supply. Actually running out of water would be an absolute catastrophe. On May 14, 2013, 11 years after Colorado’s flirtation with water supply disaster, Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper signed an executive order calling for the creation of a Colorado state water plan. The plan would aim not only to keep such water shortage nightmares from becoming reality anywhere in the state, but also to map out the actions needed to protect the Colorado we know and love. Everything, it turns out, trickles back to water.

Colorado’s Water Plan, which the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) handed in draft form to the governor on Dec. 10, 2014, is intended to demonstrate how Colorado can meet its future water supply needs while preserving the vibrant economy, viable agriculture, robust recreation and strong environment that prompt people to live here in the first place. Dauntingly, the plan must strike that balance while accounting for a growing list of threats to the state’s water supply balance sheet, from population growth to climate change.

In the decade since the 2002 drought, reams of research have emerged pointing to a large and looming gap between Colorado’s present water supply and future water demand. The State Demographer’s Office in Colorado predicts the state population will grow exponentially—from around 5.4 million people in 2014 to between 8.3 and 9.1 million by 2050—nearly doubling in some regions if the economy expands as expected. Many of the newcomers will likely live and work in the booming cities and towns of Colorado’s populous but dry eastern half, where nearly 90 percent of the state’s population now resides but only about 20 percent of its fresh water flows. If this rather breathtaking scenario plays out, the result could be a water supply gap of up to 500,000 acre-feet by 2050 that leaves the equivalent of some 2.5 million people’s water needs unmet or, rather, met in undesirable ways, reports the draft plan.

Determining how to close that gap is among the Colorado Water Plan’s major goals, particularly since the default solution—buying up agricultural water rights and transferring them to municipal and industrial uses—threatens to hobble an industry that’s vital to Colorado’s economy, environment and culture. Farmers and ranchers today use about 86 percent of the water diverted from streams and aquifers in the state, as reported by Colorado’s Division of Water Resources, making agriculture a prime target for water transfers. Yet agricultural water use provides many benefits—it produces food, preserves open space and wildlife habitat, and supports one in 10 Colorado jobs. According to the CWCB, current “buy and dry” trends already threaten to permanently dry up 35 percent of the productive agricultural land in the South Platte Basin and 20 percent of such acreage in the Colorado Basin, an outcome few if any Coloradans want to see. Instead, the water plan focuses on creative ways of sharing agricultural water between farms and cities, along with other water supply solutions, such as providing incentives for increased municipal water conservation and the construction of efficient, effective and innovative water infrastructure projects like the Prairie Waters project that Aurora built following its water supply scare in 2002. That $638 million project enables Aurora to reuse water it acquires from agricultural transfers and transbasin diversion pipelines that move water from the Western Slope, making that water go farther and boosting Aurora’s water supply by roughly 20 percent.

“The 2002 drought was ground zero for everything the water plan is trying to address,” Binney says. “It told us that the traditional ways that the suburbs did water planning weren’t going to work anymore.” To Binney, Prairie Waters is a template for how the fast-growing Front Range suburbs should meet their water needs without compromising the myriad other values associated with the state’s water.

In ordering a water plan, Hickenlooper’s advisors say the governor also hoped to change the tone of the conversation about water in Colorado from a technical discussion among water professionals to a broader look at preserving the water values Coloradans hold dear. To that end, the executive order isn’t studded with technical water terms. Instead, it identifies three overarching values that the plan should reflect: A productive economy that supports cities, agriculture, recreation and tourism; efficient and effective water infrastructure; and a strong natural environment including healthy watersheds, rivers and streams, and wildlife.

“The governor and his chief of staff made a point of not writing inside-baseball terms that no one except the water community is going to understand,” says James Eklund, director of the CWCB. “We wanted to relate to everyone from suburban dwellers to farmers, no matter what their touchstone to water was.”

Planning ahead to avoid reaching crisis mode

Since Gov. Hickenlooper issued his executive order in May 2013, state officials working on the water plan have frequently addressed the question, “Why draft a water plan now when the gap threatening our water supply looms 35 years away?” For one, they say, the gap could actually surface much sooner in some parts of the state. Plus there’s the time required for planning, permitting and building water projects, which can span 10, 20, even 60 years. There’s also a third advantage to completing a plan now: Planning in advance of crisis tends to yield better results than scrambling once a disaster is already underway.

Sean Cronin illustrates this point with a story. Cronin, executive director of the St. Vrain and Left Hand Water Conservancy District in Longmont, was deeply involved in recovery efforts after the devastating Front Range floods that destroyed homes, businesses and infrastructure across 17 eastern Colorado counties in September 2013. One of the towns hardest hit was Lyons, a small Boulder County burg formerly home to about 2,000 people, where roads, power lines and buildings were taken out when the St. Vrain River overflowed its banks. When the waters receded, crews used heavy equipment to channelize the St. Vrain River, a procedure that helped protect residents from the threat of further flooding during peak runoff the following spring but harmed fish and other wildlife by essentially sterilizing habitat.

“From an environmental point of view, that was devastating,” Cronin says. “From a human life and property perspective it was absolutely the right thing to do. That’s planning in crisis. When you have no other options you have to do something. We’re going through this water planning exercise now so that in 30 or 40 years people don’t have to make decisions in crisis that only value human life and devalue ecosystems and recreation.”

In the absence of an overarching and effective plan, the danger of a future water crisis is clear and present in Colorado.

Already, various parts of the state are feeling the consequences of unsustainable water use, with falling groundwater tables forcing cutbacks on pumping to irrigate farms and ranches in the Rio Grande and Republican basins, and numerous headwaters streams that feed the Colorado River mainstem running dry for parts of the year due to transbasin diversions to supply Eastern Slope demands. In the coming decades, population growth will likely put increasing pressure on the environmental and recreational water resources that so many Coloradans enjoy, while warmer temperatures brought on by climate change could increase crop water demand, reduce runoff, and make water planning more difficult by boosting the frequency and intensity of floods, droughts and wildfires.

According to a study called “Climate Change in Colorado,” commissioned by the CWCB and updated in 2014, Colorado’s average temperature has already risen by around 2 degrees Fahrenheit over the last 30 years. By mid-century, the study states, temperatures are expected to rise another 2.5 to 5 degrees relative to the 1971-2000 average, even if our rate of greenhouse gas emissions is relatively low. The impact of such temperature increases on precipitation is uncertain—some areas could see more while others get less—but most studies show that natural streamflows are more likely to decline than increase, particularly in the southern half of the state. The CWCB study also found that Colorado’s peak spring runoff now takes place between one and four weeks earlier than it did 30 years ago. If that trend accelerates, it could become increasingly difficult for reservoir administrators to make the spring inflow last all the way through the lengthening summer and fall.

Decades of fire suppression, aging forests, beetle-kill and drought have made Colorado’s forests vulnerable to catastrophic fires like the Black Forest Fire that burned north of Colorado Springs in

2013. Charred hillsides and denuded forests wreak havoc on water supplies and infrastructure. To reduce risk, Colorado’s Water Plan includes a section on watershed health protection. Photo By: U.S. Air Force photo/Master Sgt. Christopher DeWitt

If warmer temperatures do lead to more intense or frequent wildfires, the threat to water quality could be significant, since 80 percent of Colorado’s water flows through forested watersheds before reaching taps and irrigation ditches. To plan for that possibility, an entire section of the water plan is dedicated to watershed health. Section 7.1 recommends the creation of watershed groups like the Rio Grande Watershed Emergency Action Coordination Team (RWEACT), which was forged with the help of a $2.5 million CWCB grant during the 100,000-acre West Fork Complex Fire that burned in southern Colorado during the summer of 2013. Since the fire, RWEACT has mapped flood risk in fire-damaged areas, improved storm forecasting and disaster preparedness, and modified forest management in the Rio Grande Basin. Travis Smith, a RWEACT co-founder, CWCB board member and the superintendent of the San Luis Valley Irrigation District, says he hopes the water plan leads to more funding for watershed management groups throughout the state.

“The role of the state is to be a quick responder in bringing some money to seed some of these groups, before a disaster,” Smith says. “If a watershed has a group functioning before an event, they can interface with federal agencies and effectively deal with post-fire impacts.”

Natural disasters aside, climate change could also affect Colorado’s average water supply and undermine the state’s ability to deliver water to downstream neighbors. Colorado is a headwaters state whose numerous river basins all ultimately empty into neighboring states, and whose waters are subject to nine interstate compacts and two Supreme Court decrees governing interstate water sharing. Those agreements mean Colorado only gets to consume on average about one-third of the water originating within its watersheds, leaving two-thirds to flow to downstream states. Development of Colorado’s share of interstate waters is nearing its limit—some water rights already go unfulfilled to meet compact requirements at the state line—resulting in the need to carefully manage water use and development. Other constraints on water supply include various agreements to protect endangered species now in place on rivers around the state.

The many tributaries to a state water plan

The earliest form of water planning in Colorado was the prior appropriation doctrine, which endures today. The doctrine is encapsulated with the dictum “first in time, first in right,” and it gives anyone who puts unappropriated water to a “beneficial use” and obtains court approval a dated right to use that water. Water rights are treated as private property rights that can be bought and sold, provided a water court approves the transfer. Although primarily utilitarian, market-driven and not inherently strategic, prior appropriation provides valuable structure to govern water use and has proven flexible in accommodating new uses of water that the law deems “beneficial,” including water rights to provide for minimum streamflows and whitewater boating parks.

With a legal framework in place, the other essential ingredient in developing Colorado’s water infrastructure was money, and in the early days much of it came from the federal government. Beginning in 1902, with the founding of the Bureau of Reclamation and its first Colorado irrigation project in the Uncompahgre Valley, and accelerating in the 1930s, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration pumped cash into water infrastructure projects to help western cities grow and create post-depression jobs, state and local officials in Colorado entered an era of collaboration with the federal government that would last into the 1970s. Along with funding many irrigation and storage projects on the Western Slope, federal money was the primary source of capital for the two largest of Colorado’s 27 transbasin diversion water projects, which today collectively pipe an average of more than 580,000 acre-feet of water per year from the headwaters of western Colorado rivers and streams to the cities and agriculturally productive plains of the Eastern Slope. In general, these projects have made the Front Range critically dependent on Western Slope water.

With a legal framework in place, the other essential ingredient in developing Colorado’s water infrastructure was money, and in the early days much of it came from the federal government. Beginning in 1902, with the founding of the Bureau of Reclamation and its first Colorado irrigation project in the Uncompahgre Valley, and accelerating in the 1930s, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration pumped cash into water infrastructure projects to help western cities grow and create post-depression jobs, state and local officials in Colorado entered an era of collaboration with the federal government that would last into the 1970s. Along with funding many irrigation and storage projects on the Western Slope, federal money was the primary source of capital for the two largest of Colorado’s 27 transbasin diversion water projects, which today collectively pipe an average of more than 580,000 acre-feet of water per year from the headwaters of western Colorado rivers and streams to the cities and agriculturally productive plains of the Eastern Slope. In general, these projects have made the Front Range critically dependent on Western Slope water.

“Water planning in those days was to go ask Uncle Sam to build it and pay for it,” jokes Bill McDonald, who worked on water issues at the Colorado Department of Natural Resources (DNR) before becoming director of the CWCB from 1979 to 1990. McDonald, who is now a private consultant working for the state on Colorado’s Water Plan, says federal enthusiasm for water projects began to wane in the late 1970s and early ‘80s due to new federal environmental laws that made dams harder to build and cost-sharing arrangements that made project beneficiaries pay for a larger share of water projects.

Between 1976 and 1979, McDonald and fellow DNR staffer Chips Barry, who later became manager of Denver Water until his death in 2010, took a stab at writing a Colorado water plan after a state legislator set aside money for it in the annual budget bill. Yet despite the document’s lofty aspirations—it aimed to take stock of the state’s water values and recent changes in water law while planning for future demands—politicians and the public mostly ignored it. “There had been no clamor for any kind of plan,” McDonald remembers. “Dick Lamm was the governor at the time, and he hadn’t asked for it. It caught everybody by surprise.”

Today, McDonald believes, conditions are far riper for a state water plan to attract major public interest and input. Aside from the threats to water supply posed by climate change and drought, the flow of federal money for water projects has slowed to a trickle in recent decades, raising questions about how Colorado’s water providers will pay for major new infrastructure in the future. Population projections are more refined than they were in the 1970s, and the standard strategy for accommodating new growth, agricultural “buy and dry,” is raising more concern than ever. Finally, an increasingly broad cohort of Coloradans shares the values of the environmental movement that emerged in the 1960s, and the concept of protecting water in the stream for recreational or environmental purposes has much broader support than it did 40 years ago.

Thanks to the spread of such environmental values—and to environmental and land use laws passed in the 1970s at both the state and federal level—it has also become increasingly difficult in recent decades to build new water projects without first winning the support of both regulators and impacted communities. In the late 1980s, the cities of Denver, Colorado Springs and Aurora all saw plans for major water storage projects scrapped because of federal environmental concerns or local opposition. In 1988, the Eagle County Commissioners denied a permit for the Homestake II Reservoir project pursued by Aurora and Colorado Springs, while in 1990 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency vetoed a permit the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had issued for the Two Forks Reservoir project—put forth by Denver Water and a host of partners to store South Platte River water as well as transbasin diversion water from the Blue River on the Front Range—because of concerns about compliance with the Clean Water Act.

The EPA’s denial of the Two Forks project highlighted the tough tradeoffs inherent in meeting new water needs. Had the project been approved, some argue, it could have played a significant role in closing the Denver metro area water gap now laid out in Colorado’s Water Plan. Instead, the Two Forks veto prompted Denver Water to cap the size of its service area, and it left some suburbs in the southern metro area in the lurch, since they’d been subsisting on non-renewable groundwater and counting on Two Forks.

At the start of the 20th century, the Uncompahgre Valley, pictured here, became the first beneficiary in Colorado of the newly founded Bureau of Reclamation’s investment in water projects throughout the West—a form of de-facto water planning. The Uncompahgre Project included Taylor Park Reservoir and the Gunnison Tunnel. Photo By: Denverjeffrey/Wikimedia Commons

For all the short-term panic they caused on the Front Range, rejections like these ushered in an era of increased statewide collaboration on water issues. “[Front Range utilities] had to start paying attention to affected communities as a political force, and they had to demonstrate that they were going to use their water more efficiently than they had in the past,” says Dan Luecke, who helped lead the charge against Two Forks in the 1980s as the Rocky Mountain director for the Environmental Defense Fund and now serves on the board of the Colorado Foundation for Water Education. “West Slope interests now have some leverage and influence they didn’t have before.”

The drought of 2002 greatly boosted support for this new, more collaborative approach. Foreseeing an impending collision between drought, population growth and increasing public demand for so-called “nonconsumptive” uses of water like recreational and environmental flows, the CWCB in 2003 launched its first Statewide Water Supply Initiative (SWSI), a comprehensive assessment of water supply and demand and the status of local water planning around the state, completed with the input of local entities and interests. The first report was released in 2004 and would be periodically updated in the years that followed.

Recognizing the value of the SWSI approach, that same year DNR director and former Western Slope legislator Russell George floated the idea of a grassroots water-planning network made up of nine roundtables, based in each of Colorado’s major river basins and the Denver Metro area. Although the SWSI study also convened basin roundtables to assess local water needs and plans, George’s idea was to ensure a broad spectrum of representation in the groups through more prescriptive membership. The new roundtables would be made up of volunteer representatives from industries, cities and counties, water conservancy and conservation districts, and the agricultural, environmental and recreational communities, and members would be charged with quantifying and planning for their basin’s future water needs. To resolve longstanding disputes between the Front Range and the Western Slope over the need for new transbasin diversion projects to supply growing eastern cities, George proposed an Interbasin Compact Committee (IBCC) made up of roundtable members, gubernatorial appointees and select legislators. Much like the negotiators who hammered out the Colorado River Compact in 1922 and secured Colorado’s right to develop more slowly than California without forfeiting its water rights, George thought the IBCC could reach a deal granting the Eastern Slope enough water for its development needs over the next few decades while ensuring that the Western Slope would have the water it needed to support future growth.

With the passage of House Bill 1177 in 2005, the Colorado Water for the 21st Century Act, George’s vision for this bottom-up form of water planning became the law of the land, and since then the roundtables have held more than 850 meetings to catalogue their water needs and plan new projects. They’ve also received access to a special pot of funds, the Water Supply Reserve Account, which can be accessed to help local entities pay for scoping studies or to implement planned projects. The work of these groups, including the Basin Implementation Plans (BIPs) drafted by each roundtable in response to Gov. Hickenlooper’s 2013 executive order, forms the backbone of Colorado’s Water Plan.

Back in 2010, armed with an updated SWSI plus five years of research by the roundtables and CWCB, the IBCC issued a starkly worded letter to outgoing Colorado Gov. Bill Ritter and incoming Gov. Hickenlooper. In it, the group warned the two leaders that Colorado may not have enough water to meet its future needs if current usage and management trends continue, and that Colorado’s water management status quo would eventually lead to massive “buy and dry” of agricultural land, more environmental harm to rivers and streams, inefficient land use decisions, and continued paralysis on permitting and building new water supply projects.

Teller Lake No. 5, a recreational feature of Boulder County Parks and Open Space with a water right priority low on the totem pole, was reduced to 12 acres of hardened mud during the 2012 drought. Photo By: Jeremy Papasso

Armed with the IBCC letter and years of work from the basin roundtables and state water agencies that showed a clear need for a new direction, Gov. Hickenlooper called for a statewide water plan.

“When he issued the executive order, I think he was seeing the engagement of the roundtables and the IBCC and the conservation board and realizing they had been working at this for eight, going on nine years, and it was time to have a product,” says John Stulp, chair of the IBCC and special advisor to the governor on water policy. Although it hasn’t been easy to get to this point, Stulp says the draft water plan is a historic document that will help the state focus its limited resources as it prepares for the future and will also serve as an educational tool for Coloradans moving forward. “A lot has been accomplished and a lot of people have been involved,” says Stulp. “Chips Barry and Bill McDonald may have felt like outcasts back in the ‘70s, but they’ve got a lot of company today.”

Print

Print