The case for regionalization … when thinking big and partnering across jurisdictions can make the difference between success and failure, and where opportunities hinge on geographic, economic, political and legal realities.

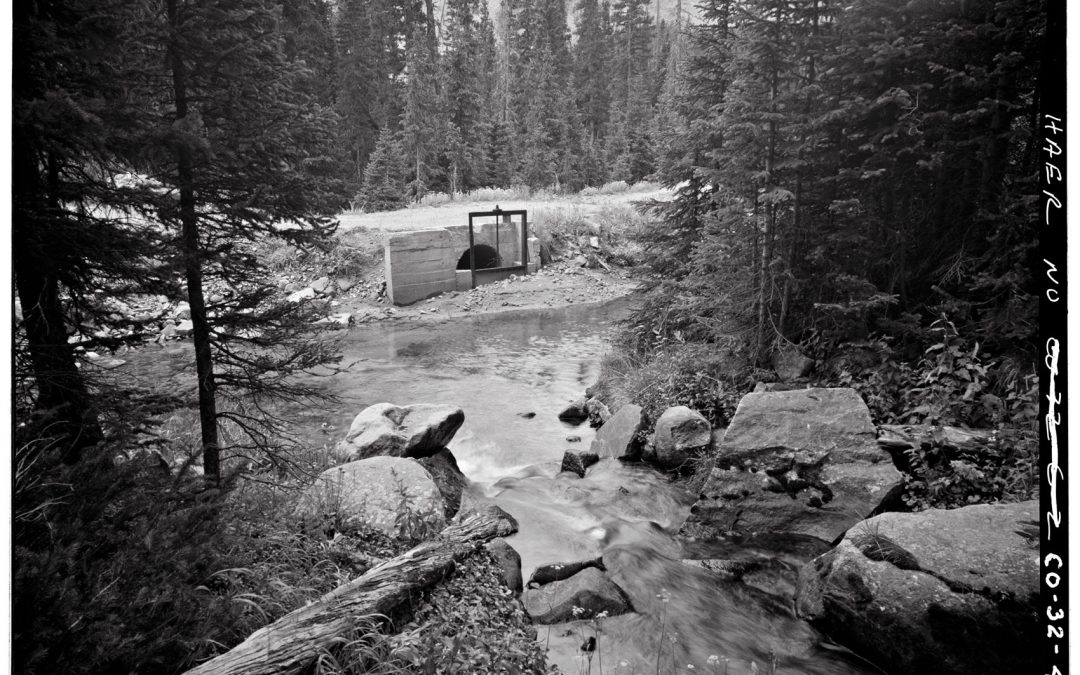

In the 1880s, Colorado’s South Platte River Basin had already seen the dark side of drought more than once or twice. In any given year, month followed month of little or no rain. The river disappeared from its channel in spots. And the Russian and German immigrants who had settled there to farm had no choice but to band together and go in search of a new, more reliable source of water for their sugar beets and corn.

They looked west to the snow-capped Never Summer Mountains in what would become Rocky Mountain National Park. They recruited bankers and politicians and farmers to help. Beet growers who couldn’t spare cash contributed their own horses, plows, harnesses, and weeks of backbreaking labor during months when the snow receded. On the crest of the Continental Divide they worked, camping with their families summer after summer until the project was done. After more than 30 years what became known as the Grand River Ditch, the oldest operating transbasin diversion in Colorado, began delivering water to the South Platte Basin, saving the region’s farm economy.

More than 100 years later, as they work to ensure the next generations of Coloradans have enough water, major players from Denver and Fort Collins to Durango and Bayfield are examining whether they, too, can join forces to establish regional water systems that are not only more economically feasible but also more environmentally sustainable than going it alone.

Denver Water, the largest utility in the state, for decades did not pursue regional projects because its agreements with the West Slope hinged on a promise not to expand its service area and divert more water from the scenic high country than it absolutely had to. Roughly half of Denver’s supplies come from transbasin diversions out of Summit and Grand counties’ Blue and Fraser rivers.

Instead, during the past 15 years, under fierce political pressure from its water-short urban neighbors and the state, Denver Water began partnering with Aurora to help fast-growing nearby cities such as Highlands Ranch, Parker and Centennial. Those South Metro communities were desperate to establish a surface water supply alternative to nonrenewable groundwater resources.

The effort became Colorado’s most ambitious regional project to date, known as WISE for Water, Infrastructure, and Supply Efficiency. Not yet operational, when completed it will recapture Denver’s treated wastewater after it is released to the South Platte River downstream and deliver it, through Aurora’s Prairie Waters Project, to 10 partnering South Metro communities. Denver and Aurora are contributing water and the South Metro entities came up with $30 million to purchase an existing pipeline to transport the water south and west.

The WISE project relies on existing infrastructure and a few new facilities, including this 2-million gallon potable water tank at Smoky Hill Road and E-470. Phot courtesy of South Metro Water

WISE came about only after Douglas County and the cities, which had grown up on a system of cheap municipal groundwater wells, came within a few years of running out of water. The region, one of the fastest growing in the metro area and the nation, was also one of the wealthiest in the state. But it had allowed development to race forward without a sustainable water supply, relying instead on nonrenewable groundwater. When it became clear that the aquifer was dropping at an alarming rate and the region’s wells were failing, the pressure to act and to convince Denver and Aurora to step in could no longer be ignored.

As with other regional projects, everyone gets something. The bigger cities, which needed to put in place some kind of drought protection, get access to their return flows in dry years, while the South Metro area can gradually reduce its dependence on the aquifer without diverting more water from the West Slope. Economically and politically it makes sense, says Denver Water CEO Jim Lochhead, but he wants to see metro Denver, home to the majority of Colorado’s 5.5 million residents, do even more to integrate regional water systems.

A concept known as “One Water” involves a newer, much bigger, and more holistic view of water, one that tracks water from its origin to its first use, to its treatment as wastewater, and finally to its integration back into the treated water supply. According to Lochhead, the concept is already being pioneered in cities like Melbourne and Sydney, Australia, as well as Amsterdam and, closer to home, San Francisco.

One Water employs aggressive conservation techniques but takes them further, considering the entire urban water network as an ecosystem of water cycles that incorporates fresh water, stormwater and wastewater. The concept makes it possible to dramatically expand water supplies without actually taking new water out of the state’s already-stressed river systems. Using a One Water approach traditional supplies are, in effect, doubled or tripled through reuse and repeated applications. But it only works if local water players coordinate and connect their systems so that water collection and treatment systems at the start of the process have a way of tapping the wastewater that is reclaimed at the end. And to fully employ One Water would require changes to laws, water quality regulations, and building codes.

Still, with this integrated approach to water supply Lochhead believes that the 500,000 acre-foot water supply gap the state has estimated may develop by 2050 could be dramatically reduced. “Urban water efficiency could take that number to something far less than what is contemplated by that state estimate,” says Lochhead. “I’m not saying that we won’t need new supplies. We will. But we can be a lot smarter and more incremental in our approach.”

Major water technology and engineering companies including General Electric, known for its sophisticated treatment membranes, and MWH Global, known for its massive infrastructure projects worldwide, have begun testing new system designs and key technologies that could enable One Water as a solution for heavily populated, water-short areas. The concept relies heavily on the reuse of existing supplies and repeated wastewater treatment, but reuse has been slow to catch on in many areas. That’s due in part to the immense energy required to treat water sufficiently, and also to the fact that systems that incorporate extensive stormwater runoff and wastewater by nature must be designed differently than traditional collection, distribution and treatment systems.

Recently, however, General Electric has acquired new technology that uses the biogas released during wastewater treatment to generate electricity. The technology is part of a pilot now underway in Chicago, at one of the nation’s largest wastewater treatment facilities, which aims to become energy neutral across its entire plant by 2023. At certain times, the recaptured energy may even be in excess of the treatment system’s needs and can be exported to the grid. GE is promoting this and related technologies as part of a changing paradigm, where wastewater treatment starts to be viewed instead as resource recovery—recovery that enables not only power generation through energy recapture but also increased water reuse.

These kinds of breakthroughs, experts believe, will allow strapped urban areas to dramatically expand their water supplies without tapping rivers. But even smaller communities without the financial resources to implement sophisticated reuse programs with their neighbors are adopting regional systems. Eight years ago outside the small town of Bayfield in southwestern Colorado, the largely rural population was watching the water wells that served as its sole source of supply become increasingly unreliable, with water quality deteriorating almost as fast as groundwater levels were dropping.

For 20 years, the region had tried to form a water district with a stable source of fresh water and a treatment plant. But the costs were staggering. In the 400 square-mile area there were fewer than 100 homes that needed taps. “They could not get the cost down to where people could afford it,” says Ed Tolen, manager of the La Plata Archuleta Water District in La Plata and Archuleta counties. Here, where poverty rates are high and median incomes low, homeowners could not afford to pick up the whole tab—roughly $10,000 to $15,000 in tap fees—the district would have needed to charge to generate enough money to build the system.

But in 2008, with support from the Southwestern Water Conservation District, local citizens were able to form a special district to tax themselves and, more importantly, the booming natural gas industry. They generated enough cash to buy a long-term water lease from the Pine River Irrigation District. With the help of loans from the Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority, they were able to pay to expand neighboring Bayfield’s water treatment plant, reserving enough capacity so that the tiny La Plata water district will always have access to treatment for its own customers. In exchange, Bayfield now has an expanded treatment plant and access to some of the new district’s pipelines, all at no cost to its own small community of 2,300 residents. “We had to find a win-win situation,” Tolen says.

In pursuit of reliable drinking water, the newly formed La Plata Archuleta Water District in southwestern Colorado found a cost-effective solution in paying neighboring Bayfield to expand its water treatment plant. Photo courtesy of FEI Engineers

The La Plata district, which generates more than $1.7 million in revenues annually, delivered its first treated water in January 2014. Now serving just 60 homes, the district will be able to serve 3,600 to 4,000 homes at buildout.

Some regional efforts elsewhere in Colorado have not yet succeeded, delayed by political disagreements and decades-long permitting battles. On northern Colorado’s Front Range, what’s known as the Windy Gap Firming Project was supposed to start seven years ago. The project includes construction of the 90,000 acre-foot Chimney Hollow Reservoir between Loveland and Longmont to store additional Windy Gap Project water from the upper Colorado in years when it is available.

The first phase of Windy Gap was built in 1985 to serve Estes Park, Fort Collins, Greeley, Loveland, Longmont and Boulder. The firming project is a much larger, 13-entity regional effort that includes Broomfield, Louisville, Lafayette, Erie, Evans, Fort Lupton, Superior, the Platte River Power Authority, the Central Weld County Water District, and the Little Thompson Water District. Although the project is now close to being finalized, the project’s sponsor, the Municipal Subdistrict of the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, has had to expand the scope of the project and dedicate new flows to the river to help mitigate environmental issues.

Eric Wilkinson, general manager of Northern Water, says that even major regional water projects such as the Windy Gap Firming Project are problematic because of the permitting delays and the unpredictable nature of the costs associated with those delays. Those kinds of problems make the process of buying agricultural lands and transferring the water to urban use seem much easier and less expensive to water-short cities, Wilkinson says, despite the long-term damage done to Colorado’s irrigated agriculture economy.

Other regional projects have gone down in flames, including the Two Forks Dam project, which was rejected by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1990 after Denver and its suburban partners had spent more than a decade and $40 million trying to win its approval. And other more recent major water projects, including Denver Water’s effort to expand Gross Reservoir in western Boulder County and another Northern Water effort—to build what’s known as the Northern Integrated Supply Project (NISP) on the northern Front Range—have yet to succeed despite the numerous cities that support them. There may be some hope ahead, however. Under Colorado’s Water Plan, adopted in December 2015, numerous policies are in place that encourage, but stop short of mandating, multi-use and multi-participant projects.

Signing of the Windy Gap Firming Project’s Record of Decision by Reclamation in December 2014. Photo courtesy of Northern Water

In addition, Wilkinson says he has been encouraged by a recent tightly focused effort by the EPA, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Bureau of Reclamation, and Colorado Department of Natural Resources to dramatically streamline the federal permitting process, another of the water plan’s action items.

Currently, any project that involves federal funding or requires a federal permit must deal with multiple agencies and stakeholder groups, all of which have different requirements for engineering, cost and environmental data. Under the federal Clean Water Act, any project that diverts from the “waters of the United States” requires a permit from the Army Corps. And most rivers and streams are considered U.S. waters. “The idea is to look at cutting out redundancies and lags in schedules [among the different agencies],” says Wilkinson. “Instead of running processes sequentially, they will run in parallel.”

As the state’s population grows, regionalizing water systems in areas that share common boundaries or at least lie close to one another will continue to make sense. As communities fill in, connecting them becomes cheaper on a per-capita basis. Look at a map of the new WISE Project and it’s clear why those communities are better served by joining forces and sharing resources, says Lochhead.

However, far-flung water districts that have suffered with inadequate financial resources, expertise or water supplies will remain harder to serve. In Tolen’s La Plata district, for instance, 25 percent of residents have had to haul water. Nearby areas outside the district are facing the same problem. But they don’t have enough residents or commercial players, such as natural gas producers, to generate the tax revenue to build a sustainable system.

The state will have to continue to look for options to help these communities, says Tom Browning, deputy director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board. Browning says other small communities that are isolated due to geography won’t be able to rely on regionalization to meet their long-term water needs.

The City of Thornton has had to largely go it alone, not because it lacks cash, but because its water rights cannot be used outside its boundaries, according to Thornton’s water project director Mark Koleber. He is in charge of a massive pipeline project that will bring water from the Grand River Ditch, now largely controlled by Thornton, south to the city. According to Koleber, although regional cooperation on the project hasn’t been possible because of its water rights limitations, the city has talked with various Weld County entities about sharing the pipeline with other small communities who might need help.

Some have suggested that communities that can’t prove they have adequate water, such as the rural areas of eastern La Plata County, should be required to join districts that do, but Tolen believes such an approach goes too far: “I would rather see the state simply require that these communities demonstrate that they are working toward a sustainable water supply.”

Still those who have been able to work successfully at the regional level have seen the power and economies that result when communities band together. “It’s not going to be a single model in the future moving forward,” says Lochhead. “But regionalization makes sense. No one can do it alone.”

Print

Print